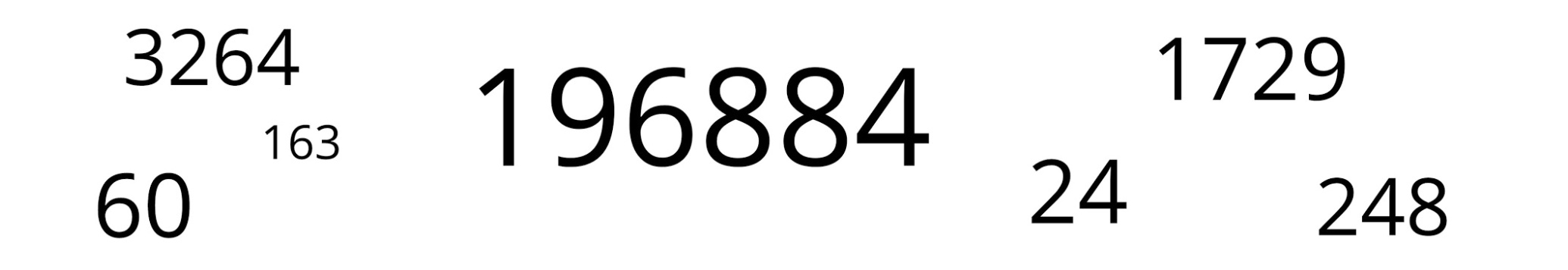

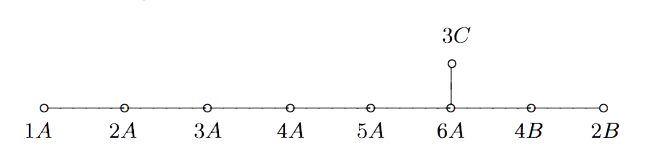

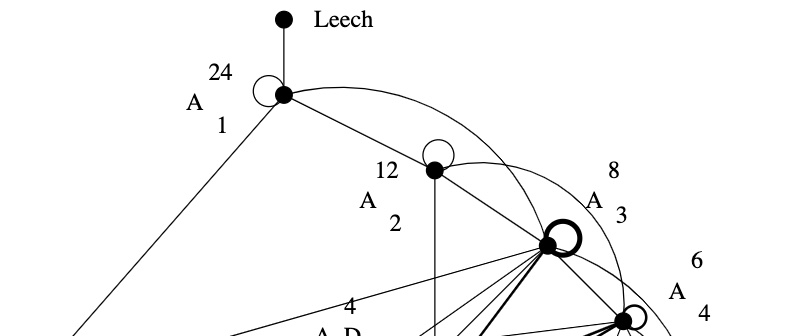

Here’s the upper part of Kneser‘s neighbourhood graph of the Niemeier lattices:

The Leech lattice has a unique neighbour, that is, among the $23$ remaining Niemeier lattices there is a unique one, $(A_1^{24})^+$, sharing an index two sub-lattice with the Leech.

How would you try to construct $(A_1^{24})^+$, an even unimodular lattice having the same roots as $A_1^{24}$?

The root lattice $A_1$ is $\sqrt{2} \mathbb{Z}$. It has two roots $\pm \sqrt{2}$, determinant $2$, its dual lattice is $A_1^* = \tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \mathbb{Z}$ and we have $A_1^*/A_1 \simeq C_2 \simeq \mathbb{F}_2$.

Thus, $A_1^{24}= \sqrt{2} \mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 24}$ has $48$ roots, determinant $2^{24}$, its dual lattice is $(A_1^{24})^* = \tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 24}$ and the quotient group $(A_1^{24})^*/A_1^{24}$ is $C_2^{24}$ isomorphic to the additive subgroup of $\mathbb{F}_2^{\oplus 24}$.

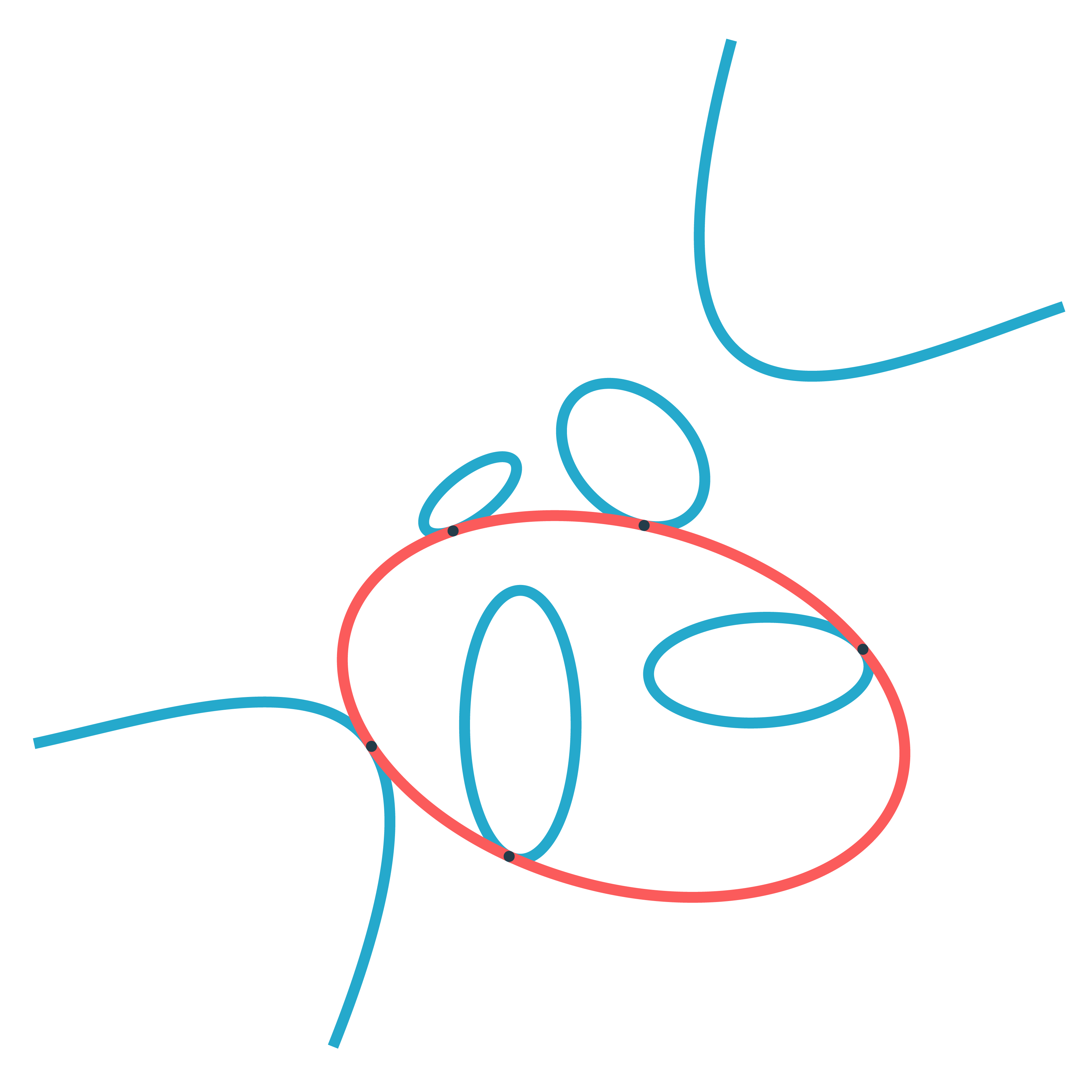

A larger lattice $A_1^{24} \subseteq L$ of index $k$ gives for the dual lattices an extension $L^* \subseteq (A_1^{24})^*$, also of index $k$. If $L$ were unimodular, then the index has to be $2^{12}$ because we have the situation

\[

A_1^{24} \subseteq L = L^* \subseteq (A_1^{24})^* \]

So, Kneser’s glue vectors form a $12$-dimensional subspace $\mathcal{C}$ in $\mathbb{F}_2^{\oplus 24}$, that is,

\[

L = \mathcal{C} \underset{\mathbb{F}_2}{\times} (A_1^{24})^* = \{ \tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \vec{v} ~|~\vec{v} \in \mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 24},~v=\vec{v}~mod~2 \in \mathcal{C} \} \]

Because $L = L^*$, the linear code $\mathcal{C}$ must be self-dual meaning that $v.w = 0$ (in $\mathbb{F}_2$) for all $v,w \in \mathcal{C}$. Further, we want that the roots of $A_1^{24}$ and $L$ are the same, so the minimal number of non-zero coordinates in $v \in \mathcal{C}$ must be $8$.

That is, $\mathcal{C}$ must be a self-dual binary code of length $24$ with Hamming distance $8$.

Marcel Golay (1902-1989) – Photo Credit

We now know that there is a unique such code, the (extended) binary Golay code, $\mathcal{C}_{24}$, which has

- one vector of weight $0$

- $759$ vectors of weight $8$ (called ‘octads’)

- $2576$ vectors of weight $12$ (called ‘dodecads’)

- $759$ vectors of weight $16$

- one vector of weight $24$

The $759$ octads form a Steiner system $S(5,8,24)$ (that is, for any $5$-subset $S$ of the $24$-coordinates there is a unique octad having its non-zero coordinates containing $S$).

Witt constructed a Steiner system $S(5,8,24)$ in his 1938 paper “Die $5$-fach transitiven Gruppen von Mathieu”, so it is not unthinkable that he checked the subspace of $\mathbb{F}_2^{\oplus 24}$ spanned by his $759$ octads to be $12$-dimensional and self-dual, thereby constructing the Niemeier-lattice $(A_1^{24})^+$ on that sunday in 1940.

John Conway classified all nine self-dual codes of length $24$ in which the weight

of every codeword is a multiple of $4$. Each one of these codes $\mathcal{C}$ gives a Niemeier lattice $\mathcal{C} \underset{\mathbb{F}_2}{\times} (A_1^{24})^*$, all but one of them having more roots than $A_1^{24}$.

Vera Pless and Neil Sloan classified all $26$ binary self-dual codes of length $24$.

Leave a Comment