“A subway is just a hole in the ground, and that hole is a maze.”

“The map is the last vestige of the old system. If you can’t read the map, you can’t use the subway.”

Eddie Jabbour in Can he get there from here? (NYT)

Sometimes, lines between adjacent stations can be uni-directional (as in the Paris Metro map below in the right upper corner, 7bis). So, it is best to view a subway map as a directed graph, with vertices the different stations, and directed arrows when there’s a service connecting two adjacent stations.

Aha! But, directed graphs form a presheaf topos. So, each and every every subway in the world comes with its own logic, its own bi-Heyting algebra!

Come again…?

Let’s say Wally (or Waldo, or Charlie) is somewhere in the Paris metro, and we want to find him. One can make statements like:

$P$ = “Wally is on line 3bis from Gambetta to Porte des Lilas.”, or

$Q$ = “Wally is traveling along line 11.”

Each sentence pinpoints Wally’s location to some directed subgraph of the full Paris metro digraph, let’s call this subgraph the ‘scope’ of the sentence.

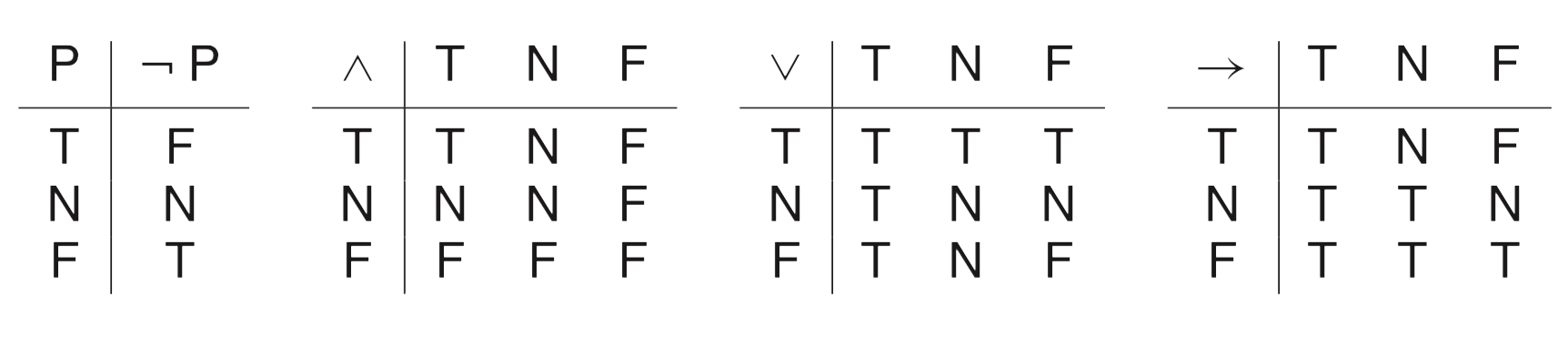

We can connect such sentences with logical connectives $\vee$ or $\wedge$ and the scope will then be the union or intersection of the respective scopes.

The scope of $P \vee Q$ is the directed subgraph of line 11 (in both directions) together with the directed subgraph of line 3bis from Gambetta to Porte des Lilas.

The scope of $P \wedge Q$ is just the vertex corresponding to Porte des Lilas.

The scope of the negation $\neg R$ of a sentence $R$ is the subgraph complement of the scope of $R$, so it is the full metro graph minus all vertices and directed edges in $R$-scope, together with all directed edges starting or ending in one of the deleted vertices.

For example, the scope of $\neg P$ does not contain directed edges along 3bis in the reverse direction, nor the edges connecting Gambetta to Pere Lachaise, and so on.

In the Paris metro logic the law of double negation does not hold.

$\neg \neg P \not= P$ as both statements have different scopes. For example, the reverse direction of line 3bis is part of the scope of $\neg \neg P$, but not of $P$.

So, although the scope of $P \wedge \neg P$ is empty, that of $P \vee \neg P$ is not the full digraph.

The logical operations $\vee$, $\wedge$ and $\neg$ do not turn the partially ordered set of all directed subgraphs of the Paris metro into a Boolean algebra structure, but rather a Heyting algebra.

Perhaps we were too drastic in removing all “problematic edges” from the scope of $\neg R$ (those with a source or target station belonging to the scope of $R$)?

We might have kept all problematic edges, and added the missing source and/or target stations to get the scope of another negation of $R$: $\sim R$.

Whereas the scope of $\neg \neg R$ always contains that of $R$, the scope of $\sim \sim R$ is contained in $R$’s scope.

The scope of $R \vee \sim R$ will indeed be the whole graph, but now $R \wedge \sim R$ does no longer have to be empty. For example, $P \wedge \sim P$ has as its scope all stations on line 3bis.

In general $R \wedge \sim R$ will be called the ‘boundary’ $\partial(R)$ of $R$. It consists of all stations within $R$’s scope that are connected to the outside of $R$’s scope.

The logical operations $\vee$, $\wedge$, $\neg$ and $\sim$ make the partially ordered set of all directed subgraphs of the Paris metro into a bi-Heyting algebra.

There’s plenty more to say about all of this (and I may come back to it later). For the impatient, there’s the paper by Reyes and Zolfaghari: Bi-Heyting Algebras, Toposes and Modalities.

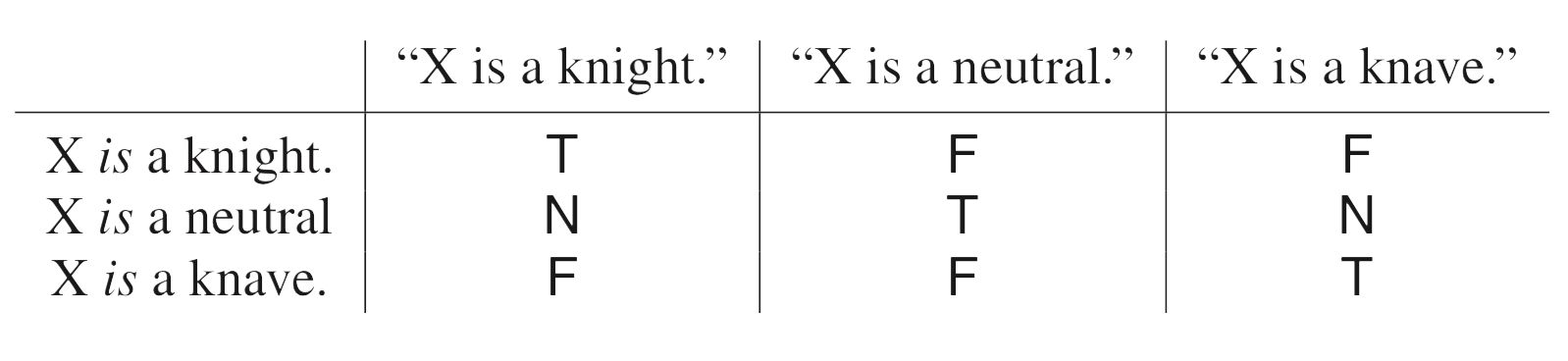

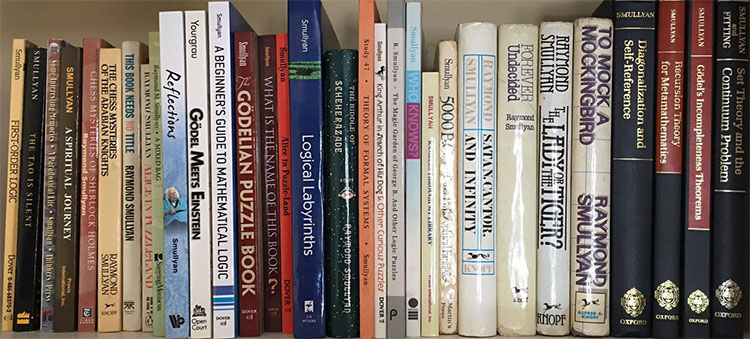

Right now, I’m more into exploring whether this setting can be used to revive an old project of mine: Heyting Smullyanesque problems (btw. the algebra in that post is not Heyting, oops!).

Leave a Comment