Can

Can

it be that one forgets an entire proof because the result doesn’t seem

important or relevant at the time? It seems the only logical explanation

for what happened last week. Raf Bocklandt asked me whether a

classification was known of all group algebras l G which are

noncommutative manifolds (that is, which are formally smooth a la Kontsevich-Rosenberg or, equivalently, quasi-free

a la Cuntz-Quillen). I said I didn’t know the answer and that it looked

like a difficult problem but at the same time it was entirely clear to

me how to attack this problem, even which book I needed to have a look

at to get started. And, indeed, after a visit to the library borrowing

Warren Dicks

lecture notes in mathematics 790 “Groups, trees and projective

modules” and browsing through it for a few minutes I had the rough

outline of the classification. As the proof is basicly a two-liner I

might as well sketch it here.

If l G is quasi-free it

must be hereditary so the augmentation ideal must be a projective

module. But Martin Dunwoody proved that this is equivalent to

G being a group acting on a (usually infinite) tree with finite

group vertex-stabilizers all of its orders being invertible in the

basefield l. Hence, by Bass-Serre theory G is the

fundamental group of a graph of finite groups (all orders being units in

l) and using this structural result it is then not difficult to

show that the group algebra l G does indeed have the lifting

property for morphisms modulo nilpotent ideals and hence is

quasi-free.

If l has characteristic zero (hence the

extra order conditions are void) one can invoke a result of Karrass

saying that quasi-freeness of l G is equivalent to G being

virtually free (that is, G has a free subgroup of finite

index). There are many interesting examples of virtually free groups.

One source are the discrete subgroups commensurable with SL(2,Z)

(among which all groups appearing in monstrous moonshine), another

source comes from the classification of rank two vectorbundles over

projective smooth curves over finite fields (see the later chapters of

Serre’s Trees). So

one can use non-commutative geometry to study the finite dimensional

representations of virtually free groups generalizing the approach with

Jan Adriaenssens in Non-commutative covers and the modular group (btw.

Jan claims that a revision of this paper will be available soon).

In order to avoid that I forget all of this once again, I’ve

written over the last couple of days a short note explaining what I know

of representations of virtually free groups (or more generally of

fundamental algebras of finite graphs of separable

l-algebras). I may (or may not) post this note on the arXiv in

the coming weeks. But, if you have a reason to be interested in this,

send me an email and I’ll send you a sneak preview.

Tag: representations

Tomorrow

Tomorrow

I’ll start with the course Projects in non-commutative geometry

in our masterclass. The idea of this course (and its companion

Projects in non-commutative algebra run by Fred Van Oystaeyen) is

that students should make a small (original if possible) work, that may

eventually lead to a publication.

At this moment the students

have seen the following : definition and examples of quasi-free algebras

(aka formally smooth algebras, non-commutative curves), their

representation varieties, their connected component semigroup and the

Euler-form on it. Last week, Markus Reineke used all this in his mini-course

Rational points of varieties associated to quasi-free

algebras. In it, Markus gave a method to compute (at least in

principle) the number of points of the non-commutative Hilbert

scheme and the varieties of simple representations over a

finite field. Here, in principle means that Markus demands a lot of

knowledge in advance : the number of points of all connected components

of all representation schemes of the algebra as well as of its scalar

extensions over finite field extensions, together with the action of the

Galois group on them … Sadly, I do not know too many examples were all

this information is known (apart from path algebras of quivers).

Therefore, it seems like a good idea to run through Markus’

calculations in some specific examples were I think one can get all this

: free products of semi-simple algebras. The motivating examples

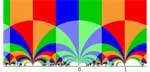

being the groupalgebra of the (projective) modular group

PSL(2,Z) = Z(2) * Z(3) and the free matrix-products $M(n,F_q) *

M(m,F_q)$. I will explain how one begins to compute things in these

examples and will also explain how to get the One

quiver to rule them all in these cases. It would be interesting to

compare the calculations we will find with those corresponding to the

path algebra of this one quiver.

As Markus set the good

example of writing out his notes and posting them, I will try to do the

same for my previous two sessions on quasi-free algebras over the next

couple of weeks.

Again I

Again I

spend the whole morning preparing my talks for tomorrow in the master

class. Here is an outline of what I will cover :

– examples of

noncommutative points and curves. Grothendieck’s characterization of

commutative regular algebras by the lifting property and a proof that

this lifting property in the category alg of all l-algebras is

equivalent to being a noncommutative curve (using the construction of a

generic square-zero extension).

– definition of the affine

scheme rep(n,A) of all n-dimensional representations (as always,

l is still arbitrary) and a proof that these schemes are smooth

using the universal property of k(rep(n,A)) (via generic

matrices).

– whereas rep(n,A) is smooth it is in general

a disjoint union of its irreducible components and one can use the

sum-map to define a semigroup structure on these components when

l is algebraically closed. I’ll give some examples of this

semigroup and outline how the construction can be extended over

arbitrary basefields (via a cocommutative coalgebra).

–

definition of the Euler-form on rep A, all finite dimensional

representations. Outline of the main steps involved in showing that the

Euler-form defines a bilinear form on the connected component semigroup

when l is algebraically closed (using Jordan-Holder sequences and

upper-semicontinuity results).

After tomorrow’s

lectures I hope you are prepared for the mini-course by Markus Reineke on non-commutative Hilbert schemes

next week.