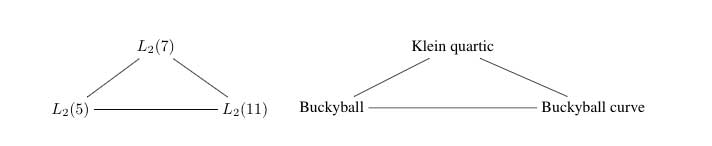

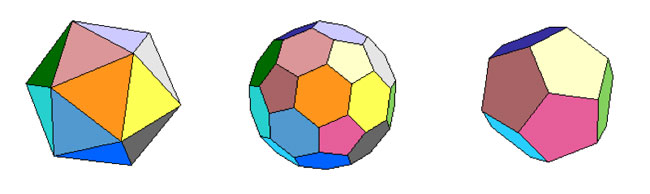

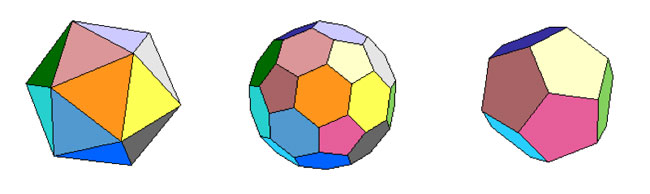

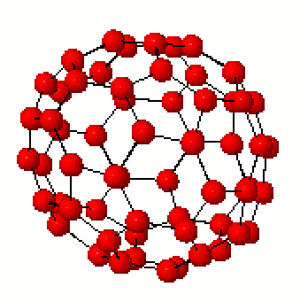

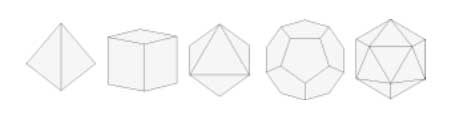

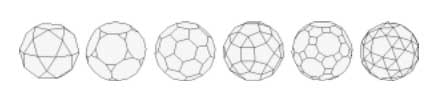

The buckyball is without doubt the hottest mahematical object at the moment (at least in Europe). Recall that the buckyball (middle) is a mixed form of two Platonic solids

the Icosahedron on the left and the Dodecahedron on the right.

For those of you who don’t know anything about football, it is that other ball-game, best described via a quote from the English player Gary Lineker

“Football is a game for 22 people that run around, play the ball, and one referee who makes a slew of mistakes, and in the end Germany always wins.”

We still have a few days left hoping for a better ending… Let’s do some bucky-maths : what is the rotation symmetry group of the buckyball?

For starters, dodeca- and icosahedron are dual solids, meaning that if you take the center of every face of a dodecahedron and connect these points by edges when the corresponding faces share an edge, you’ll end up with the icosahedron (and conversely). Therefore, both solids (as well as their mixture, the buckyball) will have the same group of rotational symmetries. Can we at least determine the number of these symmetries?

Take the dodecahedron and fix a face. It is easy to find a rotation taking this face to anyone of its five adjacent faces. In group-slang : the rotation automorphism group acts transitively on the 12 faces of the dodecohedron. Now, how many of them fix a given face? These can only be rotations with axis through the center of the face and there are exactly 5 of them preserving the pentagonal face. So, in all we have $12 \times 5 = 60 $ rotations preserving any of the three solids above. By composing two of its elements, we get another rotational symmetry, so they form a group and we would like to determine what that group is.

There is one group that springs to mind $A_5 $, the subgroup of all even permutations on 5 elements. In general, the alternating group has half as many elements as the full permutation group $S_n $, that is $\frac{1}{2} n! $ (for multiplying with the involution (1,2) gives a bijection between even and odd permutations). So, for $A_5 $ we get 60 elements and we can list them :

- the trivial permutation$~() $, being the identity.

- permutations of order two with cycle-decompostion $~(i_1,i_2)(i_3,i_4) $, and there are exactly 15 of them around when all numbers are between 1 and 5.

- permutations of order three with cycle-form $~(i_1,i_2,i_3) $ of which there are exactly 20.

- permutations of order 5 which have to form one full cycle $~(i_1,i_2,i_3,i_4,i_5) $. There are 24 of those.

Can we at least view these sets of elements as rotations of the buckyball? Well, a dodecahedron has 12 pentagobal faces. So there are 4 nontrivial rotations of order 5 for every 2 opposite faces and hence the dodecaheder (and therefore also the buckyball) has indeed 6×4=24 order 5 rotational symmetries.

The icosahedron has twenty triangles as faces, so any of the 10 pairs of opposite faces is responsible for two non-trivial rotations of order three, giving us 10×2=20 order 3 rotational symmetries of the buckyball.

The order two elements are slightly harder to see. The icosahedron has 30 edges and there is a plane going through each of the 15 pairs of opposite edges splitting the icosahedron in two. Hence rotating to interchange these two edges gives one rotational symmetry of order 2 for each of the 15 pairs.

And as 24+20+15+1(identity) = 60 we have found all the rotational symmetries and we see that they pair up nicely with the elements of $A_5 $. But do they form isomorphic groups? In other words, can the buckyball see the 5 in the group $A_5 $.

In a previous post I’ve shown that one way to see this 5 is as the number of inscribed cubes in the dodecahedron. But, there is another way to see the five based on the order 2 elements described before.

If you look at pairs of opposite edges of the icosahedron you will find that they really come in triples such that the planes determined by each pair are mutually orthogonal (it is best to feel this on ac actual icosahedron). Hence there are 15/3 = 5 such triples of mutually orthogonal symmetry planes of the icosahedron and of course any rotation permutes these triples. It takes a bit of more work to really check that this action is indeed the natural permutation action of $A_5 $ on 5 elements.

Having convinced ourselves that the group of rotations of the buckyball is indeed the alternating group $A_5 $, we can reverse the problem : can the alternating group $A_5 $ see the buckyball???

Well, for starters, it can ‘see’ the icosahedron in a truly amazing way. Look at the conjugacy classes of $A_5 $. We all know that in the full symmetric group $S_n $ elements belong to the same conjugacy class if and only if they have the same cycle decomposition and this is proved using the fact that the conjugation f a cycle $~(i_1,i_2,\ldots,i_k) $ under a permutation $\sigma \in S_n $ is equal to the cycle $~(\sigma(i_1),\sigma(i_2),\ldots,\sigma(i_k)) $ (and this gives us also the candidate needed to conjugate two partitions into each other).

Using this trick it is easy to see that all the 15 order 2 elements of $A_5 $ form one conjugacy class, as do the 20 order 3 elements. However, the 24 order 5 elements split up in two conjugacy classes of 12 elements as the permutation needed to conjugate $~(1,2,3,4,5) $ to $~(1,2,3,5,4) $ is $~(4,5) $ but this is not an element of $A_5 $.

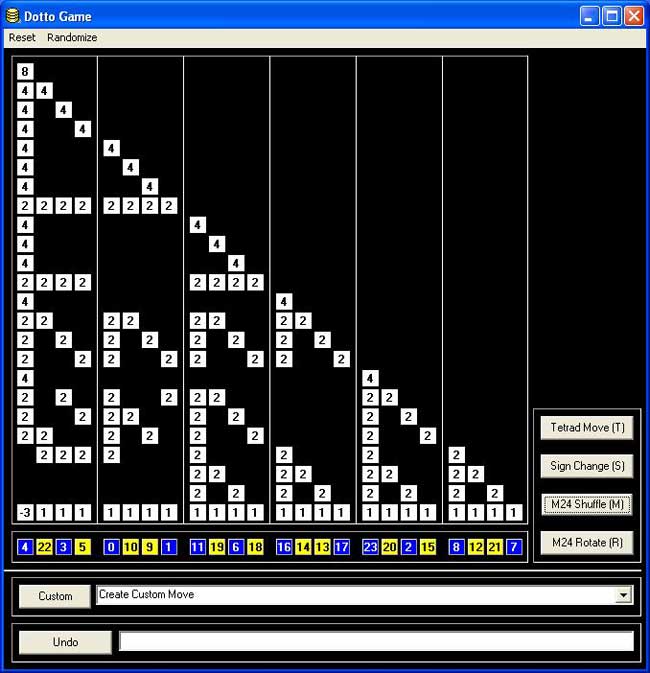

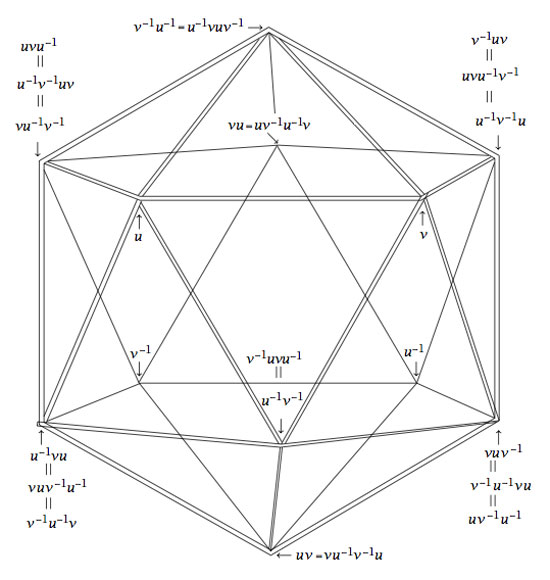

Okay, now take one of these two conjugacy classes of order 5 elements, say that of $~(1,2,3,4,5) $. It consists of 12 elements, 12 being also the number of vertices of the icosahedron. So, is there a way to identify the elements in the conjugacy class to the vertices in such a way that we can describe the edges also in terms of group-computations in $A_5 $?

Surprisingly, this is indeed the case as is demonstrated in a marvelous paper by Kostant “The graph of the truncated icosahedron and the last letter of Galois”.

Two elements $a,b $ in the conjugacy class C share an edge if and only if their product $a.b \in A_5 $ still belongs to the conjugacy class C!

So, for example $~(1,2,3,4,5).(2,1,4,3,5) = (2,5,4) $ so there is no edge between these elements, but on the other hand $~(1,2,3,4,5).(5,3,4,1,2)=(1,5,2,4,3) $ so there is an edge between these! It is no coincidence that $~(5,3,4,1,2)=(2,1,4,3,5)^{-1} $ as inverse elements correspond in the bijection to opposite vertices and for any pair of non-opposite vertices of an icosahedron it is true that either they are neighbors or any one of them is the neighbor of the opposite vertex of the other element.

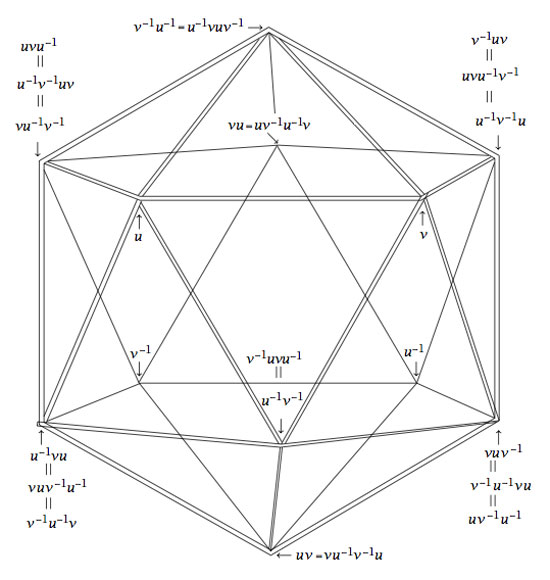

If we take $u=(1,2,3,4,5) $ and $v=(5,3,4,1,2) $ (or any two elements of the conjugacy class such that u.v is again in the conjugacy class), then one can describe all the vertices of the icosahedron group-theoretically as follows

Isn’t that nice? Well yes, you may say, but that is just the icosahedron. Can the group $A_5 $ also see the buckyball?

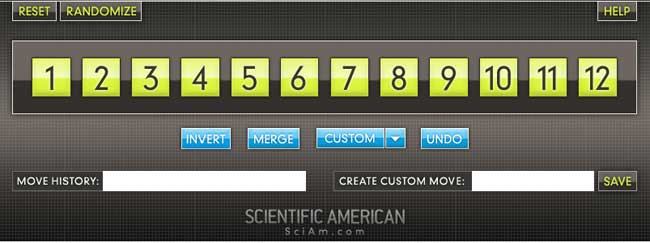

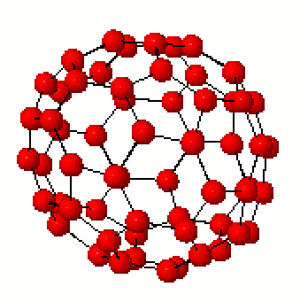

Well, let’s try a similar strategy : the buckyball has 60 vertices, exactly as many as there are elements in the group $A_5 $. Is there a way to connect certain elements in a group according to fixed rules? Yes, there is such a way and it is called the Cayley Graph of a group. It goes like this : take a set of generators ${ g_1,\ldots,g_k } $ of a group G, then connect two group element $a,b \in G $ with an edge if and only if $a = g_i.b $ or $b = g_i.a $ for some of the generators.

Back to the alternating group $A_5 $. There are several sets of generators, one of them being the elements ${ (1,2,3,4,5),(2,3)(4,5) } $. In the paper mentioned before, Kostant gives an impressive group-theoretic proof of the fact that the Cayley-graph of $A_5 $ with respect to these two generators is indeed the buckyball!

Let us allow to be lazy for once and let SAGE do the hard work for us, and let us just watch the outcome. Here’s how that’s done

A=PermutationGroup([‘(1,2,3,4,5)’,'(2,3)(4,5)’])

B=A.cayley_graph()

B.show3d()

The outcone is a nice 3-dimensional picture of the buckyball. Below you can see a still, and, if you click on it you will get a 3-dimensional model of it (first click the ‘here’ link in the new window and then you’d better control-click and set the zoom to 200% before you rotate it)

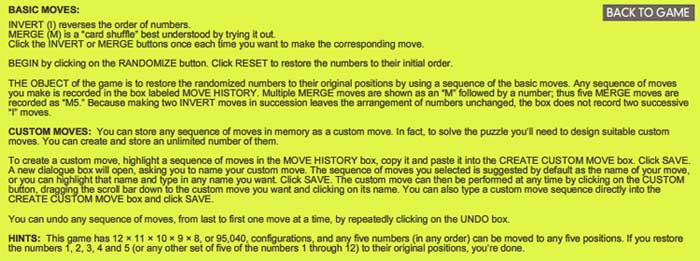

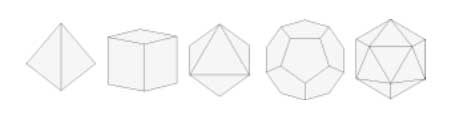

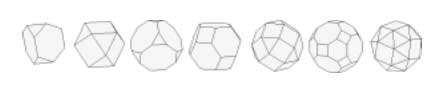

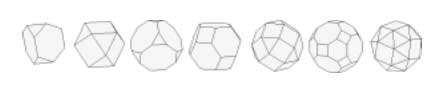

Hence, viewing this Cayley graph from different points we have convinced ourselves that it is indeed the buckyball. In fact, most (truncated) Platonic solids appear as Cayley graphs of groups with respect to specific sets of generators. For later use here is a (partial) survey (taken from Jaap’s puzzle page)

Tetrahedron : $C_2 \times C_2,[(12)(34),(13)(24),(14)(23)] $

Cube : $D_4,[(1234),(13)] $

Octahedron : $S_3,[(123),(12),(23)] $

Dodecahedron : IMPOSSIBLE

Icosahedron : $A_4,[(123),(234),(13)(24)] $

Truncated tetrahedron : $A_4,[(123),(12)(34)] $

Cuboctahedron : $A_4,[(123),(234)] $

Truncated cube : $S_4,[(123),(34)] $

Truncated octahedron : $S_4,[(1234),(12)] $

Rhombicubotahedron : $S_4,[(1234),(123)] $

Rhombitruncated cuboctahedron : IMPOSSIBLE

Snub cuboctahedron : $S_4,[(1234),(123),(34)] $

Icosidodecahedron : IMPOSSIBLE

Truncated dodecahedron : $A_5,[(124),(23)(45)] $

Truncated icosahedron : $A_5,[(12345),(23)(45)] $

Rhombicosidodecahedron : $A_5,[(12345),(124)] $

Rhombitruncated icosidodecahedron : IMPOSSIBLE

Snub Icosidodecahedron : $A_5,[(12345),(124),(23)(45)] $

Again, all these statements can be easily verified using SAGE via the method described before. Next time we will go further into the Kostant’s group-theoretic proof that the buckyball is the Cayley graph of $A_5 $ with respect to (2,5)-generators as this calculation will be crucial in the description of the buckyball curve, the genus 70 Riemann surface discovered by David Singerman and

Pablo Martin which completes the trinity corresponding to the Galois trinity