Referring to the triple of exceptional Galois groups $L_2(5),L_2(7),L_2(11) $ and its connection to the Platonic solids I wrote : “It sure seems that surprises often come in triples…”. Briefly I considered replacing triples by trinities, but then, I didnt want to sound too mystic…

Referring to the triple of exceptional Galois groups $L_2(5),L_2(7),L_2(11) $ and its connection to the Platonic solids I wrote : “It sure seems that surprises often come in triples…”. Briefly I considered replacing triples by trinities, but then, I didnt want to sound too mystic…

David Corfield of the n-category cafe and a dialogue on infinity (and perhaps other blogs I’m unaware of) pointed me to the paper Symplectization, complexification and mathematical trinities by Vladimir I. Arnold. (Update : here is a PDF-conversion of the paper)

The paper is a write-up of the second in a series of three lectures Arnold gave in june 1997 at the meeting in the Fields Institute dedicated to his 60th birthday. The goal of that lecture was to explain some mathematical dreams he had.

The next dream I want to present is an even more fantastic set of theorems and conjectures. Here I also have no theory and actually the ideas form a kind of religion rather than mathematics.

The key observation is that in mathematics one encounters many trinities. I shall present a list of examples. The main dream (or conjecture) is that all these trinities are united by some rectangular “commutative diagrams”.

I mean the existence of some “functorial” constructions connecting different trinities. The knowledge of the existence of these diagrams provides some new conjectures which might turn to be true theorems.

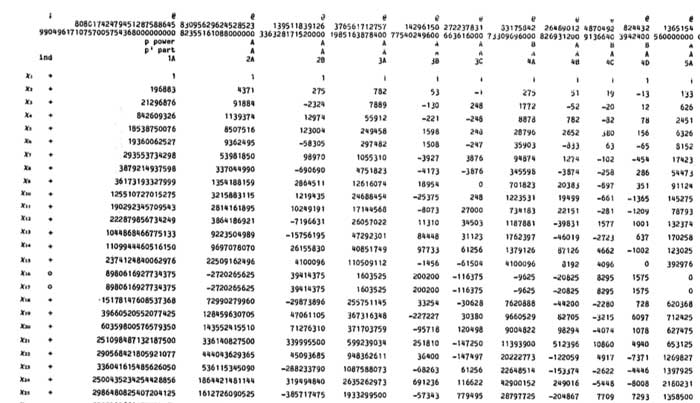

Follows a list of 12 trinities, many taken from Arnold’s field of expertise being differential geometry. I’ll restrict to the more algebraically inclined ones.

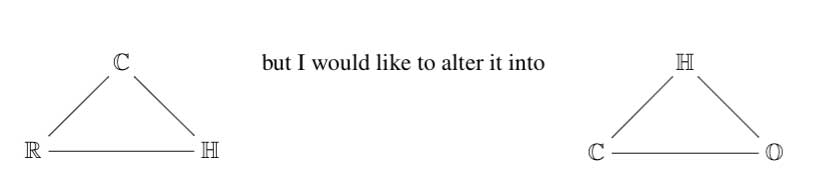

1 : “The first trinity everyone knows is”

where $\mathbb{H} $ are the Hamiltonian quaternions. The trinity on the left may be natural to differential geometers who see real and complex and hyper-Kaehler manifolds as distinct but related beasts, but I’m willing to bet that most algebraists would settle for the trinity on the right where $\mathbb{O} $ are the octonions.

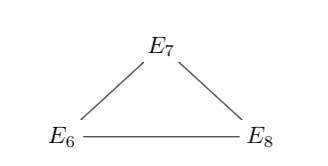

2 : The next trinity is that of the exceptional Lie algebras E6, E7 and E8.

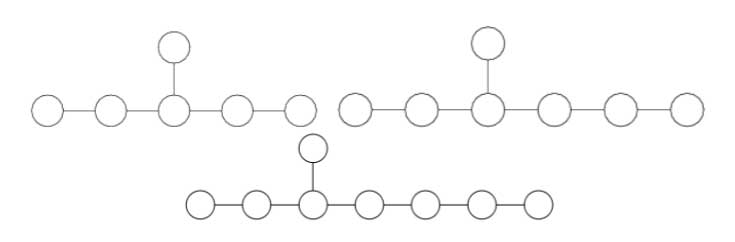

with corresponding Dynkin-Coxeter diagrams

Arnold has this to say about the apparent ubiquity of Dynkin diagrams in mathematics.

Manin told me once that the reason why we always encounter this list in many different mathematical classifications is its presence in the hardware of our brain (which is thus unable to discover a more complicated scheme).

I still hope there exists a better reason that once should be discovered.

Amen to that. I’m quite hopeful human evolution will overcome the limitations of Manin’s brain…

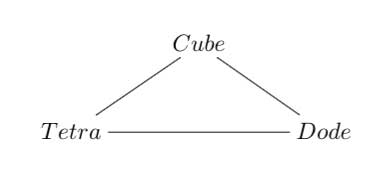

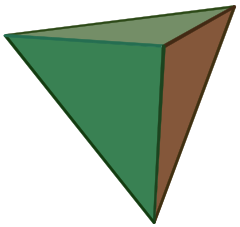

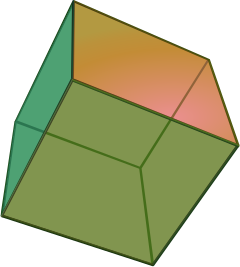

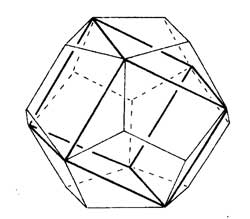

3 : Next comes the Platonic trinity of the tetrahedron, cube and dodecahedron

Clearly one can argue against this trinity as follows : a tetrahedron is a bunch of triangles such that there are exactly 3 of them meeting in each vertex, a cube is a bunch of squares, again 3 meeting in every vertex, a dodecahedron is a bunch of pentagons 3 meeting in every vertex… and we can continue the pattern. What should be a bunch a hexagons such that in each vertex exactly 3 of them meet? Well, only one possibility : it must be the hexagonal tiling (on the left below). And in normal Euclidian space we cannot have a bunch of septagons such that three of them meet in every vertex, but in hyperbolic geometry this is still possible and leads to the Klein quartic (on the right). Check out this wonderful post by John Baez for more on this.

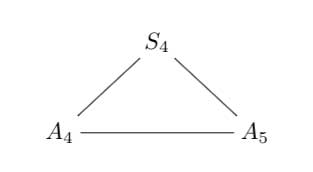

4 : The trinity of the rotation symmetry groups of the three Platonics

where $A_n $ is the alternating group on n letters and $S_n $ is the symmetric group.

Clearly, any rotation of a Platonic solid takes vertices to vertices, edges to edges and faces to faces. For the tetrahedron we can easily see the 4 of the group $A_4 $, say the 4 vertices. But what is the 4 of $S_4 $ in the case of a cube? Well, a cube has 4 body-diagonals and they are permuted under the rotational symmetries. The most difficult case is to see the $5 $ of $A_5 $ in the dodecahedron. Well, here’s the solution to this riddle

there are exactly 5 inscribed cubes in a dodecahedron and they are permuted by the rotations in the same way as $A_5 $.

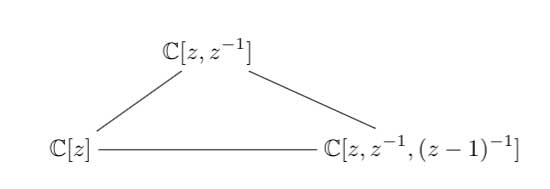

7 : The seventh trinity involves complex polynomials in one variable

the Laurant polynomials and the modular polynomials (that is, rational functions with three poles at 0,1 and $\infty $.

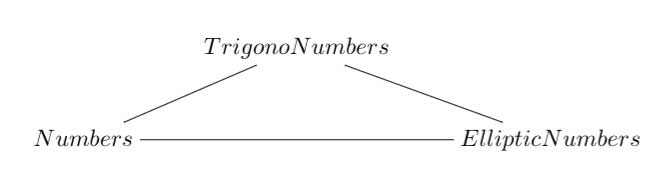

8 : The eight one is another beauty

Here ‘numbers’ are the ordinary complex numbers $\mathbb{C} $, the ‘trigonometric numbers’ are the quantum version of those (aka q-numbers) which is a one-parameter deformation and finally, the ‘elliptic numbers’ are a two-dimensional deformation. If you ever encountered a Sklyanin algebra this will sound familiar.

This trinity is based on a paper of Turaev and Frenkel and I must come back to it some time…

The paper has some other nice trinities (such as those among Whitney, Chern and Pontryagin classes) but as I cannot add anything sensible to it, let us include a few more algebraic trinities. The first one attributed by Arnold to John McKay

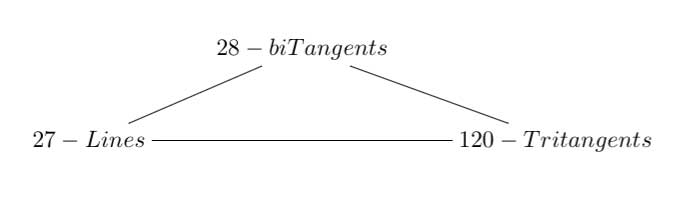

13 : A trinity parallel to the exceptional Lie algebra one is

between the 27 straight lines on a cubic surface, the 28 bitangents on a quartic plane curve and the 120 tritangent planes of a canonic sextic curve of genus 4.

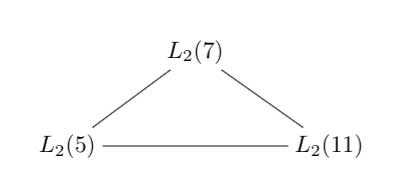

14 : The exceptional Galois groups

explained last time.

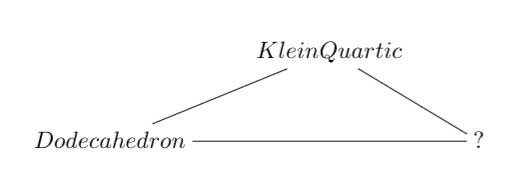

15 : The associated curves with these groups as symmetry groups (as in the previous post)

where the ? refers to the mysterious genus 70 curve. I’ll check with one of the authors whether there is still an embargo on the content of this paper and if not come back to it in full detail.

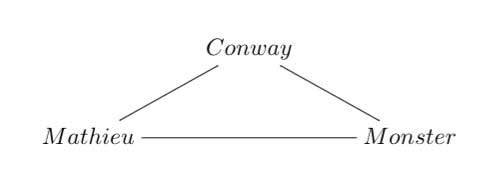

16 : The three generations of sporadic groups

Do you have other trinities you’d like to worship?

Leave a Comment