A *qurve*

is an affine algebra such that $~\Omega^1~A$ is a projective

$~A~$-bimodule. Alternatively, it is an affine algebra allowing lifts of

algebra morphisms through nilpotent ideals and as such it is the ‘right’

noncommutative generalization of Grothendieck’s smoothness criterium.

Examples of qurves include : semi-simple algebras, coordinate rings of

affine smooth curves, hereditary orders over curves, group algebras of

virtually free groups, path algebras of quivers etc.

Hence, qurves

behave a lot like curves and as such one might hope to obtain one day a

‘birational’ classification of them, if we only knew what we mean

by this. Whereas the etale classification of them is understood (see for

example One quiver to

rule them all or Qurves and quivers )

we don’t know what the Zariski topology of a qurve might be.

Usually, one assigns to a qurve $~A~$ the Abelian category of all its

finite dimensional representations $\mathbf{rep}~A$ and we would like to

equip this set with a topology of sorts. Because $~A~$ is a qurve, its

scheme of n-dimensional representations $\mathbf{rep}_n~A$ is a smooth

affine variety for each n, so clearly $\mathbf{rep}~A$ being the disjoint

union of these acquires a trivial but nice commutative topology.

However, we would like open sets to hit several of the components

$\mathbf{rep}_n~A$ thereby ‘connecting’ them to form a noncommutative

topological space associated to $~A~$.

In a noncommutative topology on

rep A I proposed a way to do this and though the main idea remains a

good one, I’ll ammend the construction next time. Whereas we don’t know

of a topology on the whole of $\mathbf{rep}~A$, there is an obvious

ordinary topology on the subset $\mathbf{simp}~A$ of all simple finite

dimensional representations, namely the induced topology of the Zariski

topology on $~\mathbf{spec}~A$, the prime spectrum of twosided prime ideals

of $~A~$. As in commutative algebraic geometry the closed subsets of the

prime spectrum consist of all prime ideals containing a given twosided

ideal. A typical open subset of the induced topology on $\mathbf{simp}~A$

hits many of the components $\mathbf{rep}_n~A$, but how can we extend it to

a topology on the whole of the category $\mathbf{rep}~A$ ?

Every

finite dimensional representation has (usually several) Jordan-Holder

filtrations with simple successive quotients, so a natural idea is to

use these filtrations to extend the topology on the simples to all

representations by restricting the top (or bottom) of the Jordan-Holder

sequence. Let W be the set of all words w such as $U_1U_2 \ldots U_k$

where each $U_i$ is an open subset of $\mathbf{simp}~A$. We can now define

the *left basic open set* $\mathcal{O}_w^l$ consisting of all finite

dimensional representations M having a Jordan-Holder sequence such that

the i-th simple factor (counted from the bottom) belongs to $U_i$.

(Similarly, we can define a *right basic open set* by counting from the

top or a *symmetric basic open set* by merely requiring that the simples

appear in order in the sequence). One final technical (but important)

detail is that we should really consider equivalence classes of left

basic opens. If w and w’ are two words we will denote by $\mathbf{rep}(w

\cup w’)$ the set of all finite dimensional representations having a

Jordan-Holder filtration with enough simple factors to have one for each

letter in w and w’. We then define $\mathcal{O}^l_w \equiv

\mathcal{O}^l_{w’}$ iff $\mathcal{O}^l_w \cap \mathbf{rep}(w \cup w’) =

\mathcal{O}^l_{w’} \cap \mathbf{rep}(w \cup w’)$. Equivalence classes of

these left basic opens form a partially ordered set (induced by

set-theoretic inclusion) with a unique minimal element 0 (the empty set

corresponding to the empty word) and a uunique maximal element 1 (the

set $\mathbf{rep}~A$ corresponding to the letter $w=\mathbf{simp}~A$).

Set-theoretic union induces an operation $\vee$ and the operation

$~\wedge$ is induced by concatenation of words, that is,

$\mathcal{O}^l_w \wedge \mathcal{O}^l_{w’} \equiv \mathcal{O}^l_{ww’}$.

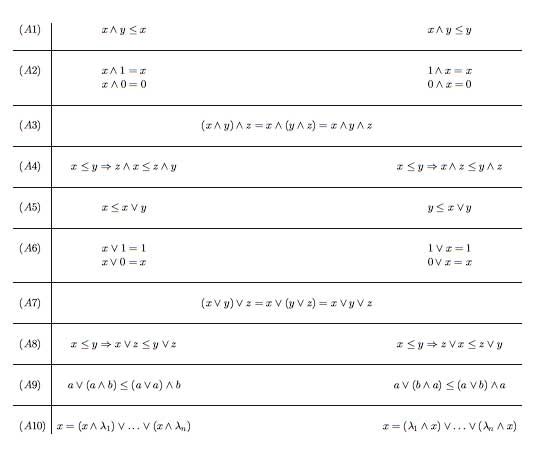

This then defines a **left noncommutative topology** on $\mathbf{rep}~A$ in

the sense of Van Oystaeyen (see [part

1](http://www.neverendingbooks.org/index.php/noncommutative-topology-1 $

). To be precise, it satisfies the axioms in the left and middle column

of the following picture  and

and

similarly, the right basic opens give a right noncommutative topology

(satisfying the axioms of the middle and right columns) whereas the

symmetric opens satisfy all axioms giving the basis of a noncommutative

topology. Even for very simple finite dimensional qurves such as

$\begin{bmatrix} \mathbb{C} & \mathbb{C} \\ 0 & \mathbb{C}

\end{bmatrix}$ this defines a properly noncommutative topology on the

Abelian category of all finite dimensional representations which

obviously respect isomorphisms so is really a noncommutative topology on

the orbits. Still, while this may give a satisfactory local definition,

in gluing qurves together one would like to relax simple representations

to *Schurian* representations. This can be done but one has to replace

the topology coming from the Zariski topology on the prime spectrum by

the partial ordering on the *bricks* of the qurve, but that will have to

wait until next time…