Last time we did recall Cantor’s addition and multiplication on ordinal numbers. Note that we can identify an ordinal number $\alpha $ with (the order type of) the set of all strictly smaller ordinals, that is, $\alpha = { \alpha’~:~\alpha’ < \alpha } $. Given two ordinals $\alpha $ and $\beta $ we will denote their Cantor-sums and products as $[ \alpha + \beta] $ and $[\alpha . \beta] $.

Last time we did recall Cantor’s addition and multiplication on ordinal numbers. Note that we can identify an ordinal number $\alpha $ with (the order type of) the set of all strictly smaller ordinals, that is, $\alpha = { \alpha’~:~\alpha’ < \alpha } $. Given two ordinals $\alpha $ and $\beta $ we will denote their Cantor-sums and products as $[ \alpha + \beta] $ and $[\alpha . \beta] $.

The reason for these square brackets is that John Conway constructed a well behaved nim-addition and nim-multiplication on all ordinals $\mathbf{On}_2 $ by imposing the ‘simplest’ rules which make $\mathbf{On}_2 $ into a field. By this we mean that, in order to define the addition $\alpha + \beta $ we must have constructed before all sums $\alpha’ + \beta $ and $\alpha + \beta’ $ with $\alpha’ < \alpha $ and $\beta’ < \beta $. If + is going to be a well-defined addition on $\mathbf{On}_2 $ clearly $\alpha + \beta $ cannot be equal to one of these previously constructed sums and the ‘simplicity rule’ asserts that we should take $\alpha+\beta $ the least ordinal different from all these sums $\alpha’+\beta $ and $\alpha+\beta’ $. In symbols, we define

$\alpha+ \beta = \mathbf{mex} { \alpha’+\beta,\alpha+ \beta’~|~\alpha’ < \alpha, \beta’ < \beta } $

where $\mathbf{mex} $ stands for ‘minimal excluded value’. If you’d ever played the game of Nim you will recognize this as the Nim-addition, at least when $\alpha $ and $\beta $ are finite ordinals (that is, natural numbers) (to nim-add two numbers n and m write them out in binary digits and add without carrying). Alternatively, the nim-sum n+m can be found applying the following two rules :

- the nim-sum of a number of distinct 2-powers is their ordinary sum (e.g. $8+4+1=13 $, and,

- the nim-sum of two equal numbers is 0.

So, all we have to do is to write numbers n and m as sums of two powers, scratch equal terms and add normally. For example, $13+7=(8+4+1)+(4+2+1)=8+2=10 $ (of course this is just digital sum without carry in disguise).

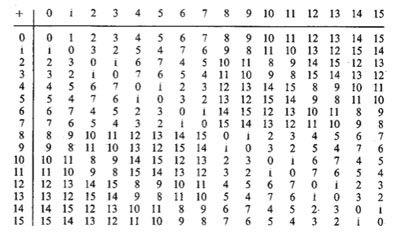

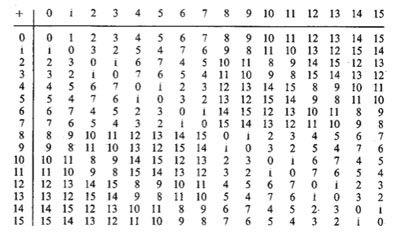

Here’s the beginning of the nim-addition table on ordinals. For example, to define $13+7 $ we have to look at all values in the first 7 entries of the row of 13 (that is, ${ 13,12,15,14,9,8,11 } $) and the first 13 entries in the column of 7 (that is, ${ 7,6,5,4,3,2,1,0,15,14,13,12,11 } $) and find the first number not included in these two sets (which is indeed $10 $).

Here’s the beginning of the nim-addition table on ordinals. For example, to define $13+7 $ we have to look at all values in the first 7 entries of the row of 13 (that is, ${ 13,12,15,14,9,8,11 } $) and the first 13 entries in the column of 7 (that is, ${ 7,6,5,4,3,2,1,0,15,14,13,12,11 } $) and find the first number not included in these two sets (which is indeed $10 $).

In fact, the above two rules allow us to compute the nim-sum of any two ordinals. Recall from last time that every ordinal can be written uniquely as as a finite sum of (ordinal) 2-powers :

$\alpha = [2^{\alpha_0} + 2^{\alpha_1} + \ldots + 2^{\alpha_k}] $, so to determine the nim-sum $\alpha+\beta $ we write both ordinals as sums of ordinal 2-powers, delete powers appearing twice and take the Cantor ordinal sum of the remaining sum.

Nim-multiplication of ordinals is a bit more complicated. Here’s the definition as a minimal excluded value

Nim-multiplication of ordinals is a bit more complicated. Here’s the definition as a minimal excluded value

$\alpha.\beta = \mathbf{mex} { \alpha’.\beta + \alpha.\beta’ – \alpha’.\beta’ } $

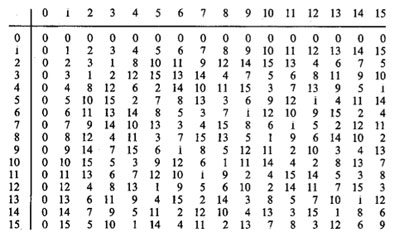

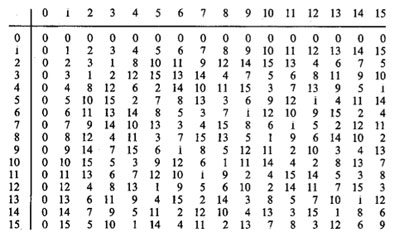

for all $\alpha’ < \alpha, \beta’ < \beta $. The rationale behind this being that both $\alpha-\alpha’ $ and $\beta – \beta’ $ are non-zero elements, so if $\mathbf{On}_2 $ is going to be a field under nim-multiplication, their product should be non-zero (and hence strictly greater than 0), that is, $~(\alpha-\alpha’).(\beta-\beta’) > 0 $. Rewriting this we get $\alpha.\beta > \alpha’.\beta+\alpha.\beta’-\alpha’.\beta’ $ and again the ‘simplicity rule’ asserts that $\alpha.\beta $ should be the least ordinal satisfying all these inequalities, leading to the $\mathbf{mex} $-definition above. The table gives the beginning of the nim-multiplication table for ordinals. For finite ordinals n and m there is a simple 2 line procedure to compute their nim-product, similar to the addition-rules mentioned before :

- the nim-product of a number of distinct Fermat 2-powers (that is, numbers of the form $2^{2^n} $) is their ordinary product (for example, $16.4.2=128 $), and,

- the square of a Fermat 2-power is its sesquimultiple (that is, the number obtained by multiplying with $1\frac{1}{2} $ in the ordinary sense). That is, $2^2=3,4^2=6,16^2=24,… $

Using these rules, associativity and distributivity and our addition rules it is now easy to work out the nim-multiplication $n.m $ : write out n and m as sums of (multiplications by 2-powers) of Fermat 2-powers and apply the rules. Here’s an example

$5.9=(4+1).(4.2+1)=4^2.2+4.2+4+1=6.2+8+4+1=(4+2).2+13=4.2+2^2+13=8+3+13=6 $

Clearly, we’d love to have a similar procedure to calculate the nim-product $\alpha.\beta $ of arbitrary ordinals, or at least those smaller than $\omega^{\omega^{\omega}} $ (recall that Conway proved that this ordinal is isomorphic to the algebraic closure $\overline{\mathbb{F}}_2 $ of the field of two elements). From now on we restrict to such ‘small’ ordinals and we introduce the following special elements :

$\kappa_{2^n} = [2^{2^{n-1}}] $ (these are the Fermat 2-powers) and for all primes $p > 2 $ we define

$\kappa_{p^n} = [\omega^{\omega^{k-1}.p^{n-1}}] $ where $k $ is the number of primes strictly smaller than $p $ (that is, for p=3 we have k=1, for p=5, k=2 etc.).

Again by associativity and distributivity we will be able to multiply two ordinals $< \omega^{\omega^{\omega}} $ if we know how to multiply a product

$[\omega^{\alpha}.2^{n_0}].[\omega^{\beta}.2^{m_0}] $ with $\alpha,\beta < [\omega^{\omega}] $ and $n_0,m_0 \in \mathbb{N} $.

Now, $\alpha $ can be written uniquely as $[\omega^t.n_t+\omega^{t-1}.n_{t-1}+\ldots+\omega.n_2 + n_1] $ with t and all $n_i $ natural numbers. Write each $n_k $ in base $p $ where $p $ is the $k+1 $-th prime number, that is, we have for $n_0,n_1,\ldots,n_t $ an expression

$n_k=[\sum_j p^j.m(j,k)] $ with $0 \leq m(j,k) < p $

The point of all this is that any of the special elements we want to multiply can be written as a unique expression as a decreasing product

$[\omega^{\alpha}.2^{n_0}] = [ \prod_q \kappa_q^m(q) ] $

where $q $ runs over all prime powers. The crucial fact now is that for this decreasing product we have a rule similar to addition of 2-powers, that is Conway-products coincide with the Cantor-products

$[ \prod_q \kappa_q^m(q) ] = \prod_q \kappa_q^m(q) $

But then, using associativity and commutativity of the Conway-product we can ‘nearly’ describe all products $[\omega^{\alpha}.2^{n_0}].[\omega^{\beta}.2^{m_0}] $. The remaining problem being that it may happen that for some q we will end up with an exponent $m(q)+m(q’)>p $. But this can be solved if we know how to take p-powers. The rules for this are as follows

$~(\kappa_{2^n})^2 = \kappa_{2^n} + \prod_{1 \leq i < n} \kappa_{2^i} $, for 2-powers, and,

$~(\kappa_{p^n})^p = \kappa_{p^{n-1}} $ for a prime $p > 2 $ and for $n \geq 2 $, and finally

$~(\kappa_p)^p = \alpha_p $ for a prime $p > 2 $, where $\alpha_p $ is the smallest ordinal $< \kappa_p $ which cannot be written as a p-power $\beta^p $ with $\beta < \kappa_p $. Summarizing : if we will be able to find these mysterious elements $\alpha_p $ for all prime numbers p, we are able to multiply in $[\omega^{\omega^{\omega}}]=\overline{\mathbb{F}}_2 $.

Let us determine the first one. We have that $\kappa_3 = \omega $ so we are looking for the smallest natural number $n < \omega $ which cannot be written in num-multiplication as $n=m^3 $ for $m < \omega $ (that is, also $m $ a natural number). Clearly $1=1^3 $ but what about 2? Can 2 be a third root of a natural number wrt. nim-multiplication? From the tabel above we see that 2 has order 3 whence its cube root must be an element of order 9. Now, the only finite ordinals that are subfields of $\mathbf{On}_2 $ are precisely the Fermat 2-powers, so if there is a finite cube root of 2, it must be contained in one of the finite fields $[2^{2^n}] $ (of which the mutiplicative group has order $2^{2^n}-1 $ and one easily shows that 9 cannot be a divisor of any of the numbers $2^{2^n}-1 $, that is, 2 doesn’t have a finte 3-th root in nim! Phrased differently, we found our first mystery number $\alpha_3 = 2 $. That is, we have the marvelous identity in nim-arithmetic

$\omega^3 = 2 $

Okay, so what is $\alpha_5 $? Well, we have $\kappa_5 = [\omega^{\omega}] $ and we have to look for the smallest ordinal which cannot be written as a 5-th root. By inspection of the finite nim-table we see that 1,2 and 3 have 5-th roots in $\omega $ but 4 does not! The reason being that 4 has order 15 (check in the finite field [16]) and 25 cannot divide any number of the form $2^{2^n}-1 $. That is, $\alpha_5=4 $ giving another crazy nim-identity

$~(\omega^{\omega})^5 = 4 $

And, surprises continue to pop up… Conway showed that $\alpha_7 = \omega+1 $ giving the nim-identity $~(\omega^{\omega^2})^7 = \omega+1 $. The proof of this already uses some clever finite field arguments. Because 7 doesn’t divide any number $2^{2^n}-1 $, none of the finite subfields $[2^{2^n}] $ contains a 7-th root of unity, so the 7-power map is injective whence surjective, so all finite ordinal have finite 7-th roots! That is, $\alpha_7 \geq \omega $. Because $\omega $ lies in a cubic extension of the finite field [4], the field generated by $\omega $ has 64 elements and so its multiplicative group is cyclic of order 63 and as $\omega $ has order 9, it must be a 7-th power in this field. But, as the only 7th powers in that field are precisely the powers of $\omega $ and by inspection $\omega+1 $ is not a 7-th power in that field (and hence also not in any field extension obtained by adjoining square, cube and fifth roots) so $\alpha_7=\omega +1 $.

Conway did stop at $\alpha_7 $ but I’ve always been intrigued by that one line in ONAG p.61 : “Hendrik Lenstra has computed $\alpha_p $ for $p \leq 43 $”. Next time we will see how Lenstra managed to do this and we will use sage to extend his list a bit further, including the first open case : $\alpha_{47}= \omega^{\omega^7}+1 $.

For an enjoyable video on all of this, see Conway’s MSRI lecture on Infinite Games. The nim-arithmetic part is towards the end of the lecture but watching the whole video is a genuine treat!

Over the week-end I read The artist and the mathematician (subtitle : The story of Nicolas Bourbaki, the genius mathematician who never existed) by Amir D. Aczel.

Over the week-end I read The artist and the mathematician (subtitle : The story of Nicolas Bourbaki, the genius mathematician who never existed) by Amir D. Aczel.

Here’s the beginning of the nim-addition table on ordinals. For example, to define $13+7 $ we have to look at all values in the first 7 entries of the row of 13 (that is, ${ 13,12,15,14,9,8,11 } $) and the first 13 entries in the column of 7 (that is, ${ 7,6,5,4,3,2,1,0,15,14,13,12,11 } $) and find the first number not included in these two sets (which is indeed $10 $).

Here’s the beginning of the nim-addition table on ordinals. For example, to define $13+7 $ we have to look at all values in the first 7 entries of the row of 13 (that is, ${ 13,12,15,14,9,8,11 } $) and the first 13 entries in the column of 7 (that is, ${ 7,6,5,4,3,2,1,0,15,14,13,12,11 } $) and find the first number not included in these two sets (which is indeed $10 $). Nim-multiplication of ordinals is a bit more complicated. Here’s the definition as a minimal excluded value

Nim-multiplication of ordinals is a bit more complicated. Here’s the definition as a minimal excluded value Surely, Connes is aware of the fact that there exists a nice canonical recursive construction of $\overline{\mathbb{F}}_2 $ due to John Conway, using

Surely, Connes is aware of the fact that there exists a nice canonical recursive construction of $\overline{\mathbb{F}}_2 $ due to John Conway, using