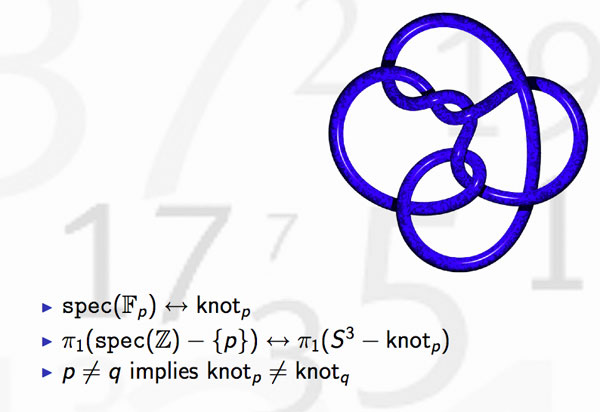

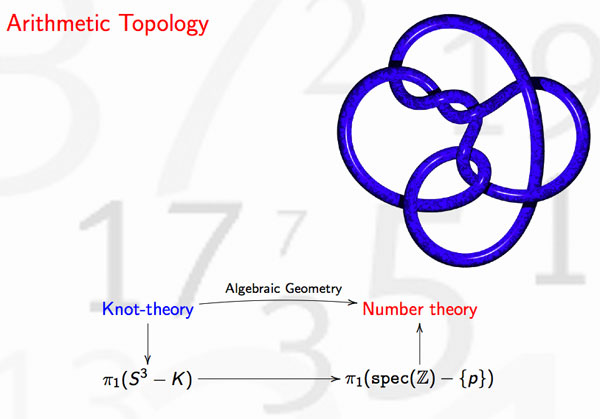

Last time we discovered that the mental picture to view prime numbers as knots in $S^3$ was first dreamed up by David Mumford. Today, we’ll focus on where and when this happened.

3. When did Mazur write his unpublished preprint?

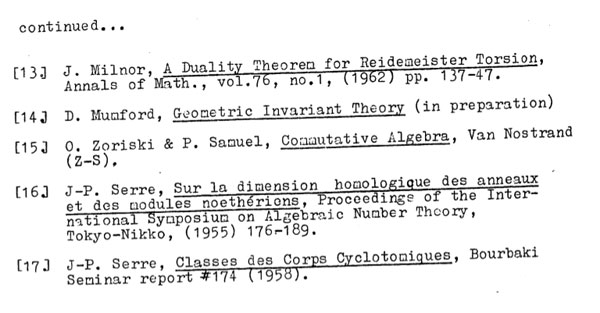

According to his own website, Barry Mazur did write the paper Remarks on the Alexander polynomial in 1963 or 1964. A quick look at the references gives us a coarse lower- and upper-estimate.

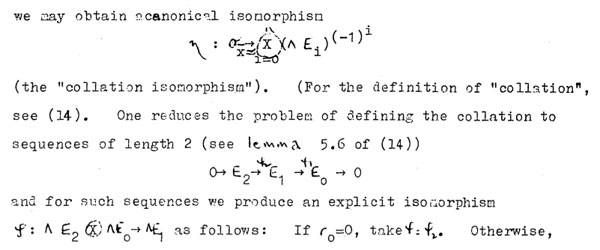

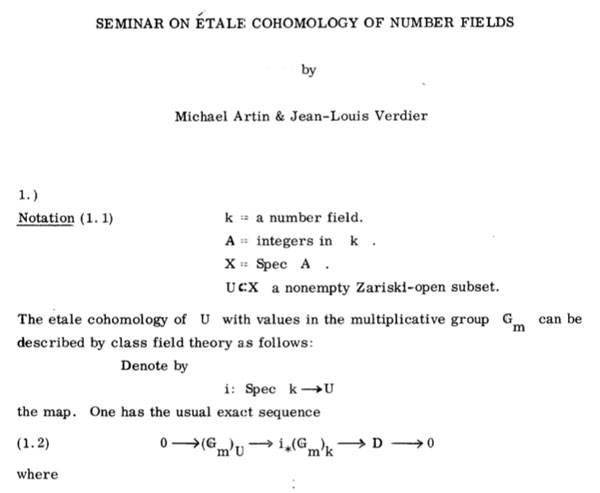

Apart from a paper by Iwasawa and one by Milnor, all references predate 1962 giving us a lower-bound. More interesting is reference (14) to David Mumford’s Geometric Invariant Theory (GIT) which was first published in 1965 and is referred to as ‘in preparation’, so the paper was written no later than 1965. If we look a bit closer we see than some GIT-references are very precise

indicating that Mazur must have had the final version of GIT to consult, making it rather difficult to believe that the preprint was written late 1963 or early 1964.

Mazur’s dating of the preprint is probably based on this penciled note on the frontpage of the only surviving copy of the preprint

It reads : “Date from about 63/64, H.R. Morton”. Hugh Morton of Liverpool University confirms that it is indeed his writing on the preprint.

Further, he told me that early 64 Christopher Zeeman held a Topology Symposium in Cambridge UK, where Hugh was a graduate student at the time and, as far as he could recall, Mazur attended that conference and gave him the preprint on that occasion, whence the 63/64 dating. Hugh kindly offered to double-check this with Terry Wall who cannot remember Mazur attending that particular conference.

In fact, we will see that a more correct dating of the Mazur-preprint will be : late 1964 or early 1965.

4. The birthday : July 10th 1964

Clearly, Mumford’s insight predates the Mazur-preprint. In the first section, Mazur mentions ‘Grothendieck cohomology groups’ rather than ‘Etale cohomology groups’.

At the time, Artin’s seminar notes on Grothendieck topologies (spring 1962) were widely distributed, and Artin and Grothendieck were in the process of developing etale cohomology in their Paris 1963/64 seminar SGA 4, while Mumford was working on GIT in Harvard.

Mike Artin, David Mumford and Jean-Louis Verdier all attended the Woods Hole conference from july 6 till july 31 1964, famous for producing the Atiyah-Bott fixed point theorem (according to Fulton first proved by Verdier at the conference).

Mike Artin, David Mumford and Jean-Louis Verdier all attended the Woods Hole conference from july 6 till july 31 1964, famous for producing the Atiyah-Bott fixed point theorem (according to Fulton first proved by Verdier at the conference).

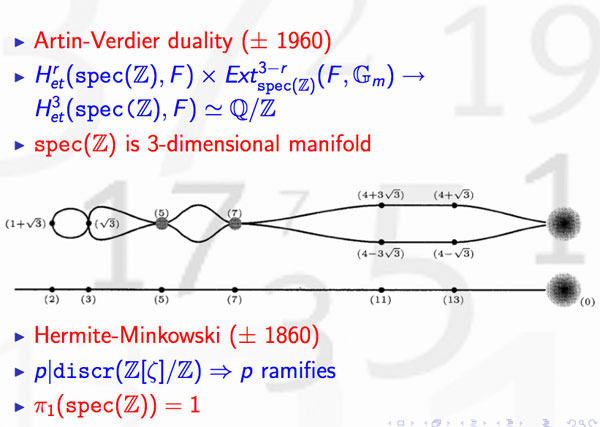

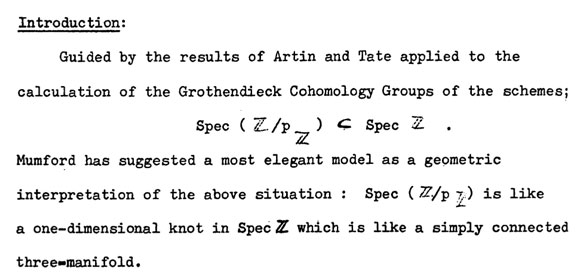

Etale cohomology was a hot topic at that conference. On july 10th there were three talks, Artin spoke on ‘Etale cohomology of schemes’, Verdier on ‘A duality theorem in the etale cohomology of schemes’ and John Tate on ‘Etale cohomology over number fields’.

After a first week of talks, more informal seminars were organized, including the Atiyah-Bott seminar leading to the ‘Woods hole duality theorem’ and one by Lubin-Tate and Serre on elliptic curves and formal groups. Two seminars adressed Etale Cohomology.

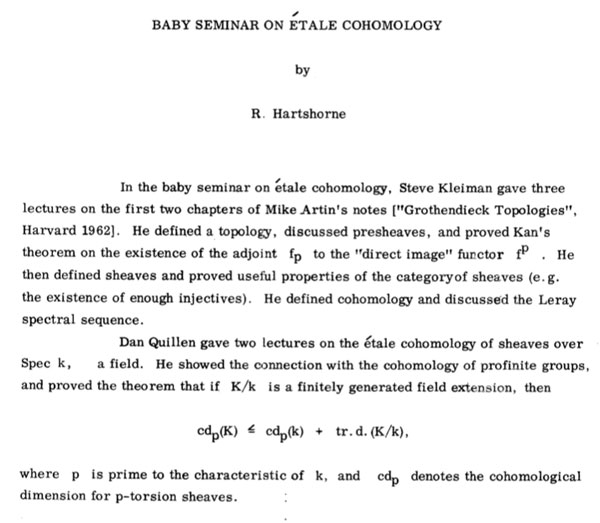

Artin and Verdier ran a seminar on the etale cohomology of number fields leading to their duality result, and, three young turks : Daniel Quillen, Steve Kleiman and Robin Hartshorne ran a Baby Seminar on Etale cohomology

Probably it is safe to say that the talks by Artin, Verdier and Tate on July 10th sparked the primes=knots idea, and if not then, a couple of days later.

5. The birthplace : the Whitney Estate

The ‘Woods Hole’ conference took place at the Whitney Estate and all the lectures took place in the rustic rooms of the main building and the participants (and their families) were housed in rented cottages in the neighborhood, for the duration of the summer.

The only picture i managed to find from the Whitney house comes from a rather surprising source : Gardeners and Caretakers ofWoods Hole. Anyway, here it is :

Probably, the knots=primes analogy was first dreamed up inside, or in the immediate neighborhood, on a walk to or from the cottages, overlooking the harbor.

Leave a Comment