The Clique (Twenty Øne Piløts fanatic fanbase) is convinced that the nine Bishops of Dema were modelled after the Bourbaki-group.

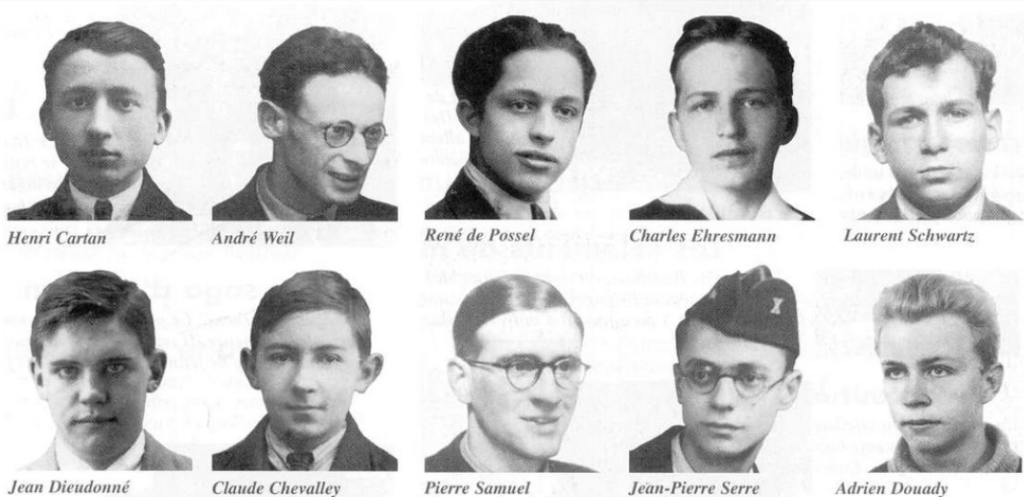

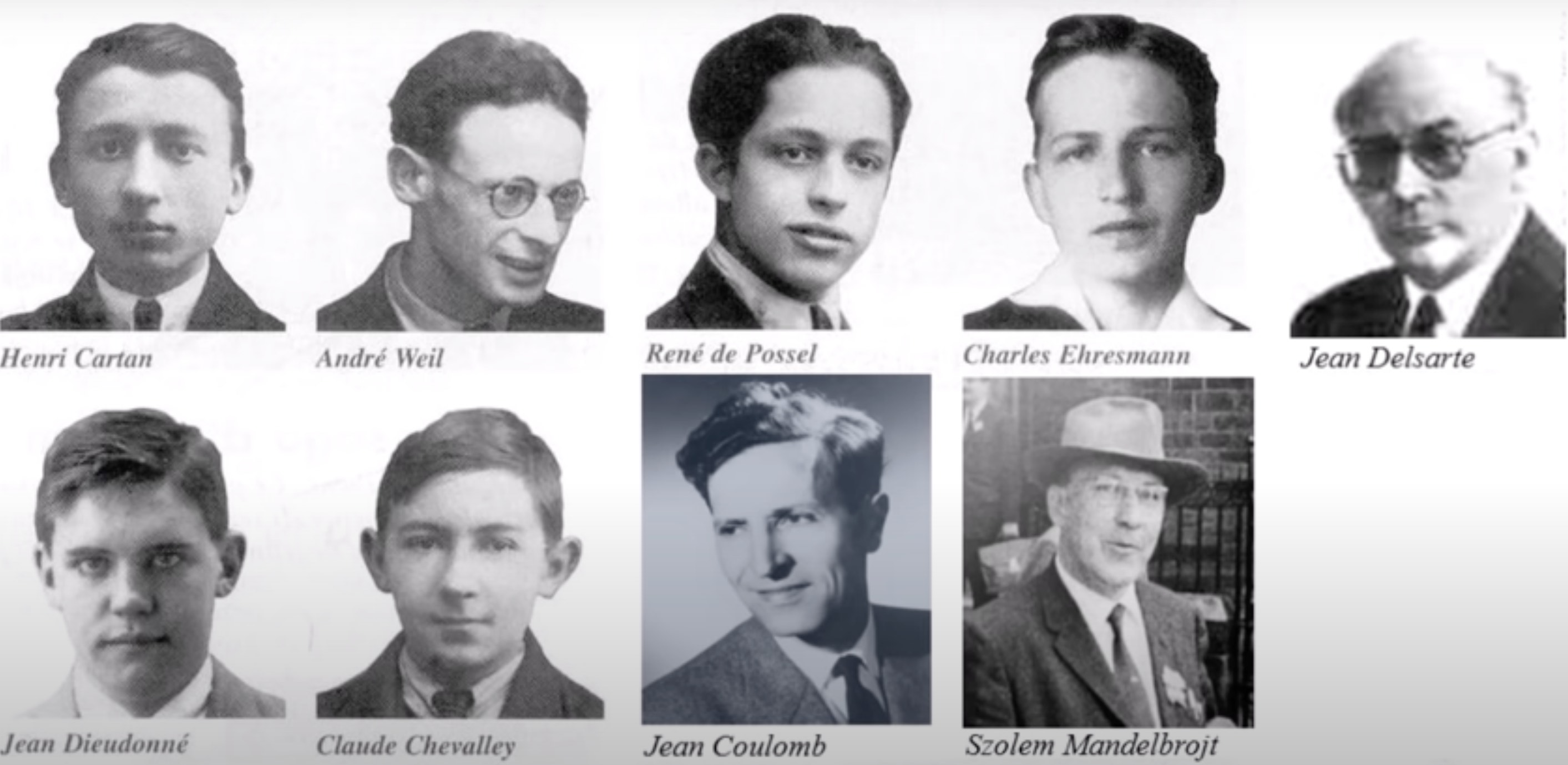

It is therefore of no surprise to see a Photoshopped version circulating of this classic picture of some youthful Bourbaki-members (note Jean-Pierre Serre poster-boying for Elon Musk’s site),

replacing some of them with much older photos of other members. Crucial seems to be that there are just nine of them.

I don’t know whether the Clique hijacked Bourbaki’s Wikipedia page, or whether they were inspired by its content to select those people, but if you look at that Wikipedia page you’ll see in the right hand column:

Founders

- Henri Cartan

- Claude Chevalley

- Jean Coulomb

- Jean Delsarte

- Jean Dieudonné

- Charles Ehresmann

- René de Possel

- André Weil

Really? Come on.

We know for a fact that Charles Ehresmann was brought in to replace Jean Leray, and Jean Coulomb to replace Paul Dubreil. Surely, replacements can’t be founders, can they?

Well, unfortunately it is not quite that simple. There’s this silly semantic discussion: from what moment on can you call someone a Bourbaki-member…

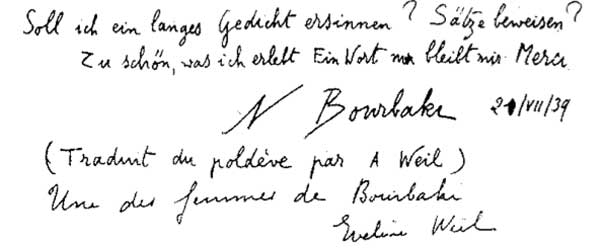

The collective name ‘Nicolas Bourbaki’ was adopted only at the Bourbaki-congress in Besse in July 1935 (see also this post).

But, before the Besse-meeting there were ten ‘proto-Bourbaki’ meetings, the first one on December 10th, 1934 in Cafe Capoulade. These meetings have been described masterly by Liliane Beaulieu in A Parisian Cafe and Ten Proto-Bourbaki Meetings (1934-35) (btw. if you know a direct link to the pdf, please drop it in the comments).

During these early meetings, the group called itself ‘The Committee for the Treatise on Analysis’, and not yet Bourbaki, whence the confusion.

Do we take the Capoulade-1934 meeting as the origin of the Bourbaki group (in which case the founding-members would be Cartan, Chevalley, De Possel, Delsarte, Dieudonne, and Weil), or was the Bourbaki-group founded at the Besse-congress in 1935 (when Cartan, Chevalley, Coulomb, De Possel, Dieudonne, Mandelbrojt, and Weil were present)?

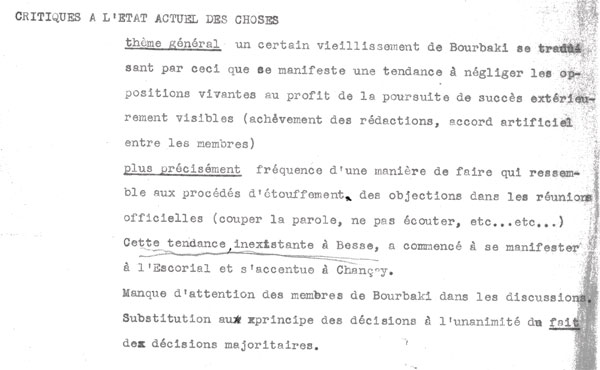

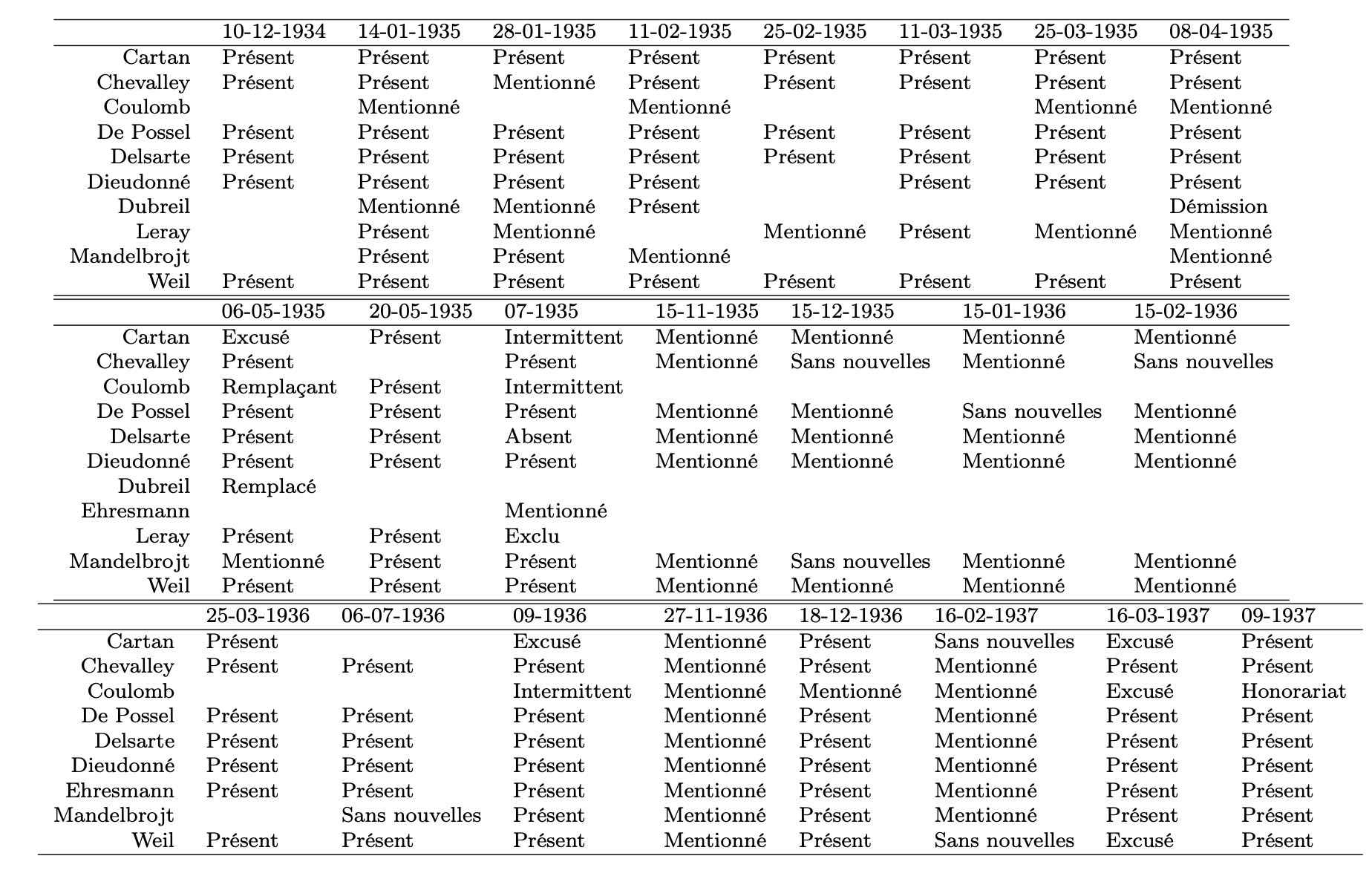

Here’s a summary of which people were present at all meetings from December 1934 until the second Chancay-congress in September 1939, taken from Gatien Ricotier ‘Projets collectifs et personnels autour de Bourbaki dans les années 1930 à 1950′:

07-1935 is the Besse-congress, 09-1936 is the ‘Escorial’-congress (or Chancay 1) and 09-1937 is the second Chancay-congress. The ten dates prior to July 1935 are the proto-Bourbaki meetings.

Even though Delsarte was not present at the Besse-1935 congress, and De Possel moved to Algiers and left Bourbaki in 1941, I assume most people would agree that the six people present at the first Capoulade-meeting (Cartan, Chevalley, De Possel, Delsarte, Dieudonne, and Weil) should certainly be counted among the Bourbaki founding members.

What about the others?

We can safely eliminate Dubreil: he was present at just one proto-Bourbaki meeting and left the group in April 1935.

Also Leray’s case is straightforward: he was even excluded from the Besse-meeting as he didn’t contribute much to the group, and later he vehemently opposed Bourbaki, as we’ve seen.

Coulomb’s role seems to restrict to securing a venue for the Besse-meeting as he was ‘physicien-adjoint’ at the ‘Observatoire Physique du Globe du Puy-de-Dome’.

Because of this he could rarely attend the Julia-seminar or Bourbaki-meetings, and his interest in mathematical physics was a bit far from the themes pursued in the seminar or by Bourbaki. It seems he only contributed one small text, in the form of a letter. Due to his limited attendance, even after officially been asked to replace Dubreil, he can hardly be counted as a founding member.

This leaves Szolem Mandelbrojt and Charles Ehresmann.

We’ve already described Mandelbrojt as the odd-man-out among the early Bourbakis. According to the Bourbaki archive he only contributed one text. On the other hand, he also played a role in organising the Besse-meeting and in providing financial support for Bourbaki. Because he was present already early on (from the second proto-Bourbaki meeting) until the Chancay-1937 meeting, some people will count him among the founding members.

Personally I wouldn’t call Charles Ehresmann a Bourbaki founding member because he joined too late in the process (March 1936). Still, purists (those who argue that Bourbaki was founded at Besse) will say that at that meeting he was put forward to replace Jean Leray, and later contributed actively to Bourbaki’s meetings and work, and for that reason should be included among the founding members.

What do you think?

How many Bourbaki founding members are there? Six (the Capoulade-gang), seven (+Mandelbrojt), eight (+Mandelbrojt and Ehresmann), or do you still think there were nine of them?

In this series:

- Bourbaki and TØP : East is up

- Bourbaki = Bishops or Banditos?

- Where’s Bourbaki’s Dema?

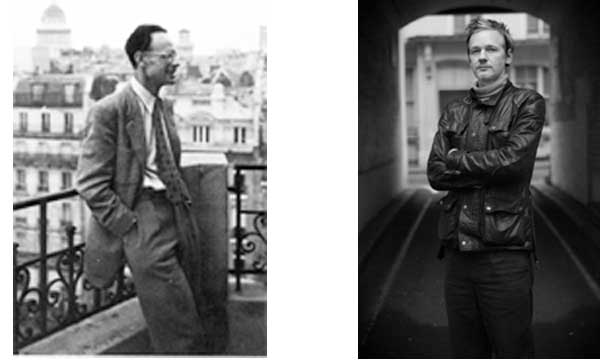

- Weil photos used in Dema-lore

- Dema2Trench, AND REpeat

- TØP PhotoShop mysteries

- 9 Bourbaki founding members, really?

- Bourbaki and Dema, two remarks

- Clancy and Nancago

- What about Simone Weil?

- Vialism versus Weilism

- The dangerous bend symbol