Someone from down under commented on the group think post yesterday :

Nice post, but I might humbly suggest that there’s not much in it that anyone would disagree with. I’d be interested in your thoughts on the following:

1. While many doomed research programs have the seven symptoms you mention, so do some very promising research programs. For instance, you could argue that Grothendieck’s school did. While it did eventually explode, it remains one of the high points in the history of mathematics. But at the time, many people (Mordell, Siegel) thought it was all garbage. Indeed there was even doubt into the late eighties. Is there anything close to a necessary and sufficient condition that an outsider can use to get some idea of whether a research group is doing work that will last?

2. Pretty much everyone thinks they’re underappreciated. It’s easy to advise them to pull a Perelman because it costs you nothing. But most unappreciated researchers are unappreciated for a good reason. How can unappreciated researchers decide whether their ideas really are good or not before spending ten years of their lives finding out?

First the easy bit : the ‘do a Perelman’-sentence seems to have been misread by several people (probably due to my inadequate English). I never suggested ‘unappreciated researchers’ to pull a Perelman but rather the key figures in seemingly successful groups making outrageous claims for power-reasons. Here is what I actually wrote

An aspect of these groupthinking science-groups that worries me most of all is their making of exagerated claims to potential applications, not supported (yet) by solid proof. Short-time effect may be to attract more people to the subject and to keep doubting followers on board, but in the long term (at least if the claimed results remain out of reach) this will destroy the subject itself (and, sadly enough, also closeby subjects making no outrageous claims!). My advice to people making such claims is : do a Perelman! Rather than doing a PR-job, devote yourself for as long as it takes to prove your hopes, somewhere in splendid isolation and come back victoriously. I have a spare set of keys if you are in search for the perfect location!

Before I will try to answer both questions let me stress that this is just my personal opinion to which I attach no particular value. Sure, I will forget things and will over-stress others. You can always leave a comment if you think I did, but I will not enter a discussion. I think it is important that a person develops his or her own scientific ethic and tries to live by it. 1. Is there anything close to a necessary and sufficient condition that an outsider can use to get some idea of whether a research group is doing work that will last? Clearly, the short answer to this is “no”. Still, there are some signs an outsider might pick up to form an opinion. – What is the average age of the leading people in the group? (the lower, the better) – The percentage of talks given by young people at a typical conference of the group (the higher, the better) – The part of a typical talk in the subject spend setting up notation, referring to previous results and namedropping (the lower, the better) – The number of group-outsiders invited to speak at a typical conference (the higher, the better) – The number of self-references in a typical paper (the lower, the better) – The number of publications by the group in non-group controlled journals (the higher, the better) – The number of group-controlled journals (the lower, the better) – The readablity of survey papers and textbooks on the subject (the higher, the better) – The complexity of motivating examples not covered by competing theories (the lower, the better) – The number of subject-gurus (the higher, the better) – The number of phd-students per guru (the lower, the better) – The number of main open problems (the higher, the better) – The Erdoes-like number of a typical group-member wrt. John Conway (the lower, the better) Okay, Im starting to drift but I hope you get the point. It is not that difficult to set up your own tools to measure the amount to which a scientific group suffers from group think. Whether the group will make a long-lasting contribution is another matter which is much harder to predict. Here, I would go for questions like : – Does the theory offer a new insight into classical & central mathematical objects such as groups, curves, modular forms, Dynkin diagrams etc. ? – Does the theory offer tools to reduce the complexity of a problem or does is instead add a layer of technical complexity? That is, are they practicing mathematics or obscurification? 2. How can unappreciated researchers decide whether their ideas really are good or not before spending ten years of their lives finding out? Here is my twofold advice to all the ‘unappreciated’ : (1) be at least as critical to your own work as you are to that of others (it is likely you will find out that you are rightfully under-appreciated compared to others) and (2) enjoy the tiny tokens of appreciation because they are likely all that you will ever get. Speaking for myself, I do not feel unappreciated compared to what I did. I did prove a couple of good results to which adequate reference is given and I had a couple of crazy ideas which were ridiculed by some at the time. A silly sense of satisfaction comes from watching the very same people years later fall over each other trying to reclaim some of the credit for these ideas. Okay, it may not have the same status of recognition as a Fields medal or a plenary talk at the ICM but it is enough to put a smile on my face from time to time and to continue stubbornly with my own ideas.

and related it to

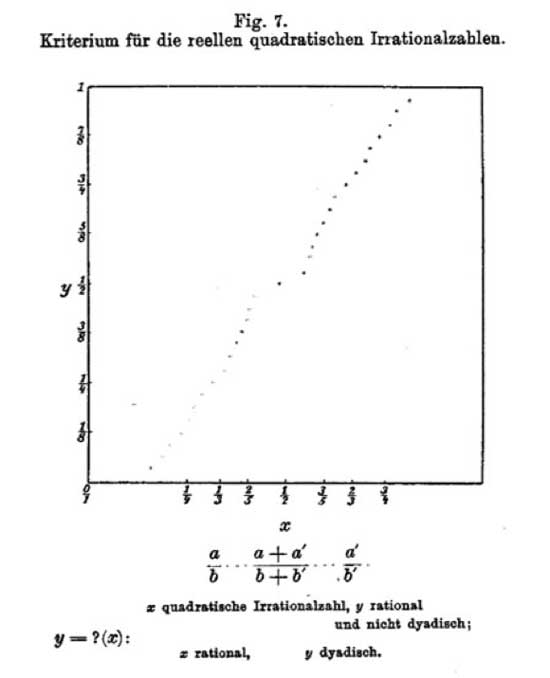

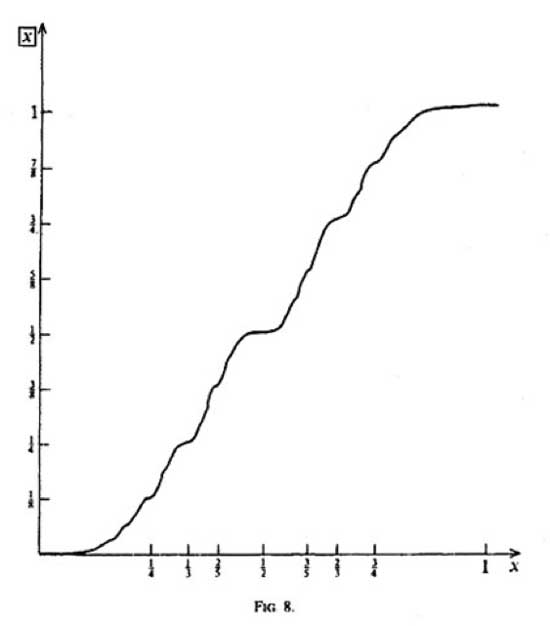

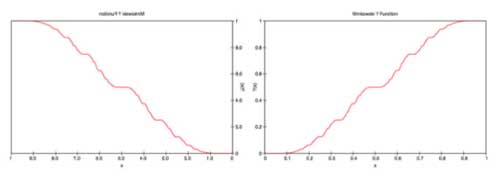

and related it to But from this

But from this That is, $?(x-1) = 1 – ?(x) $ Observe that the left-hand

That is, $?(x-1) = 1 – ?(x) $ Observe that the left-hand

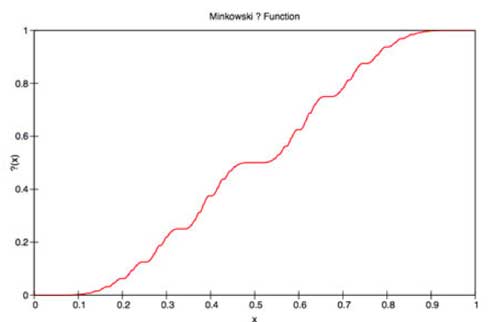

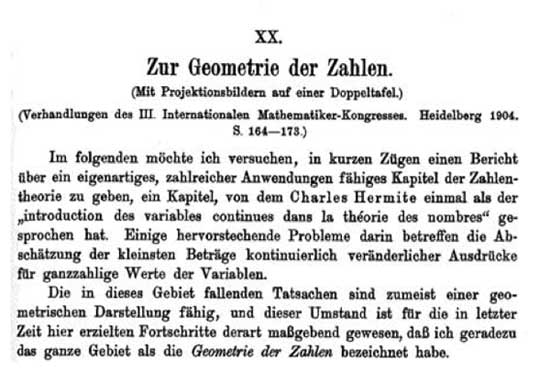

What concerns

What concerns