On March 20th, David Smith, Joseph Myers, Craig Kaplan and Chaim Goodman-Strauss announced on the arXiv that they’d found an ein-Stein (a stone), that is, one piece to tile the entire plane, in uncountably many different ways, all of them non-periodic (that is, the pattern does not even allow a translation symmetry).

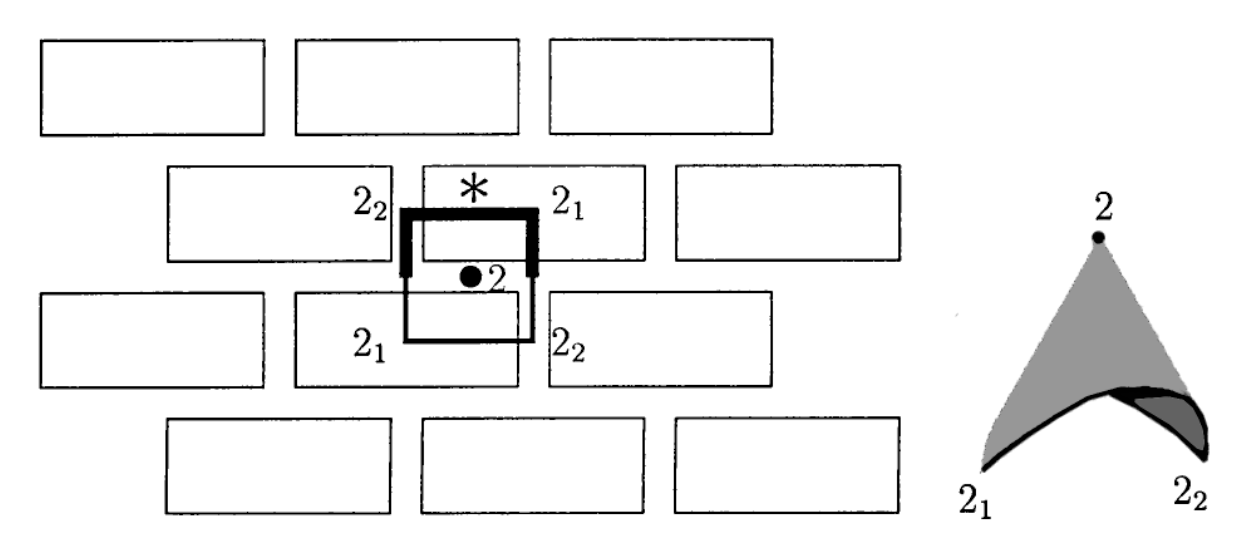

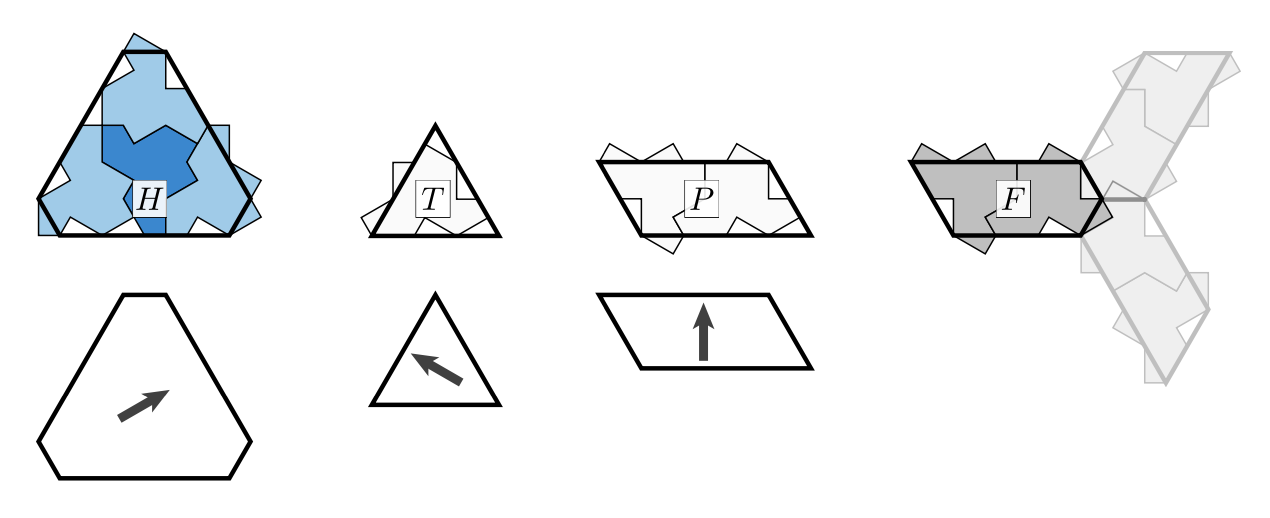

This einStein, called the ‘hat’ (some prefer ‘t-shirt’), has a very simple form : you take the most symmetric of all plane tessellations, $\ast 632$ in Conway’s notation, and glue sixteen copies of its orbifold (or if you so prefer, eight ‘kites’) to form the gray region below:

(all images copied from the aperiodic monotile paper)

Surprisingly, you do not even need to impose gluing conditions (unlike in the two-piece aperiodic kite and dart Penrose tilings), but you’ll need flipped hats to fill up the gaps left.

A few years ago, I wrote some posts on Penrose tilings, including details on inflation and deflation, aperiodicity, uncountability, Conway worms, and more:

- Penrose’s aperiodic tilings

- Conway’s musical sequences

- Conway’s musical sequences (2)

- de Bruijn’s pentagrids

- de Bruijn’s pentagrids (2)

- Penrose tilings and non-commutative geometry

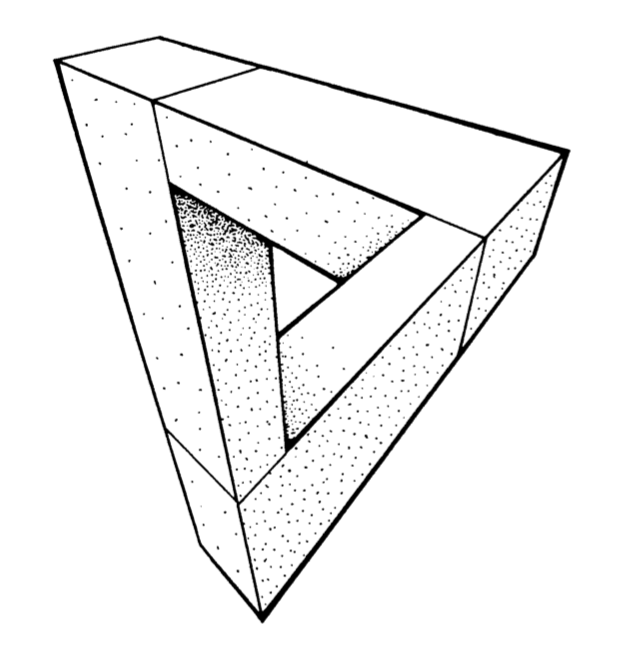

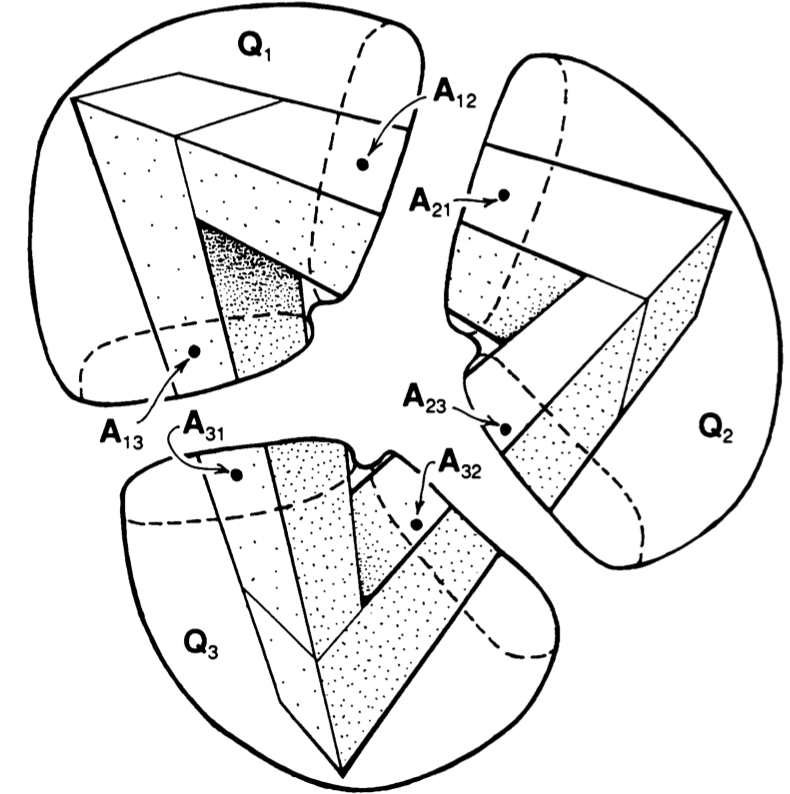

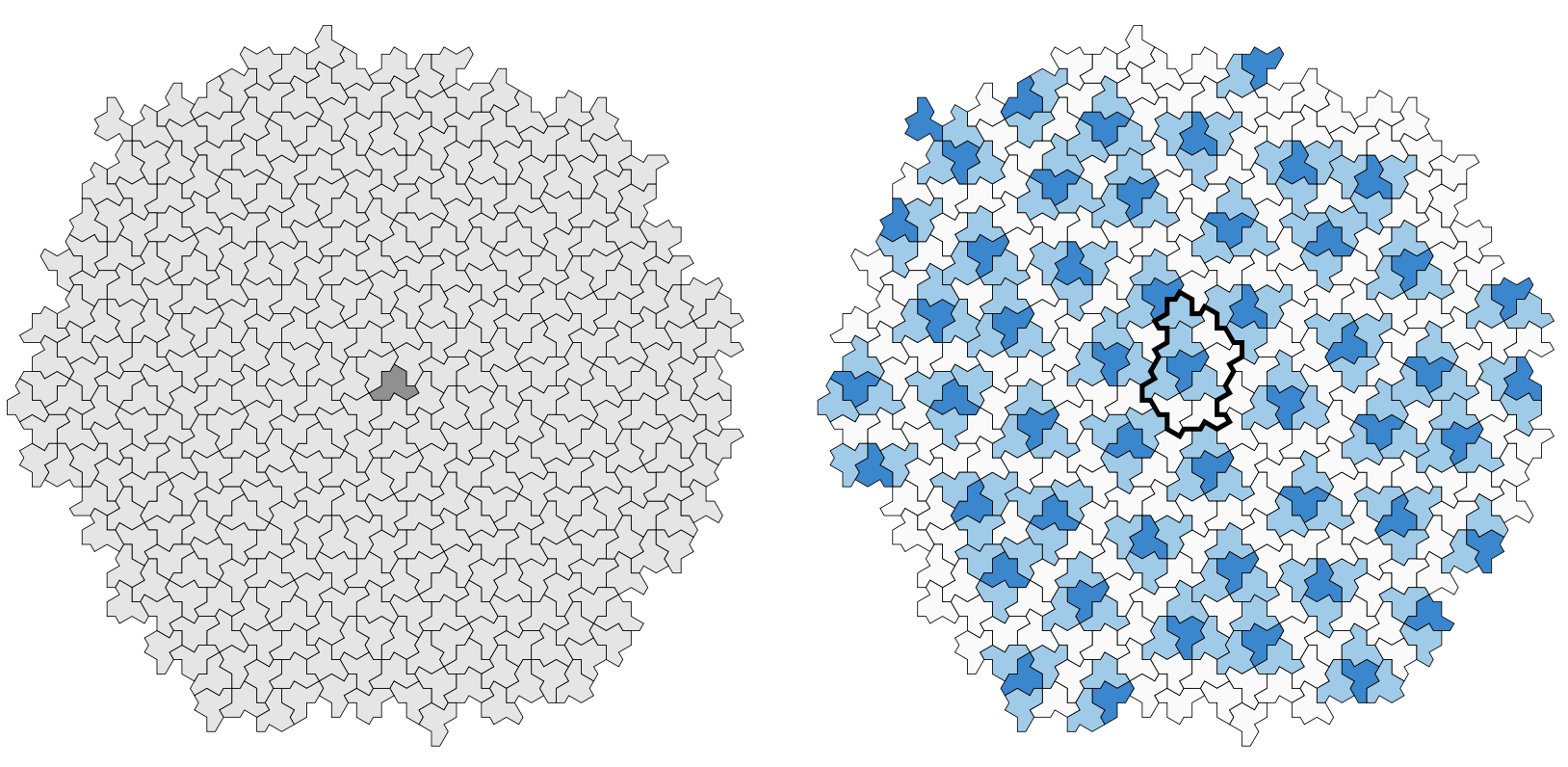

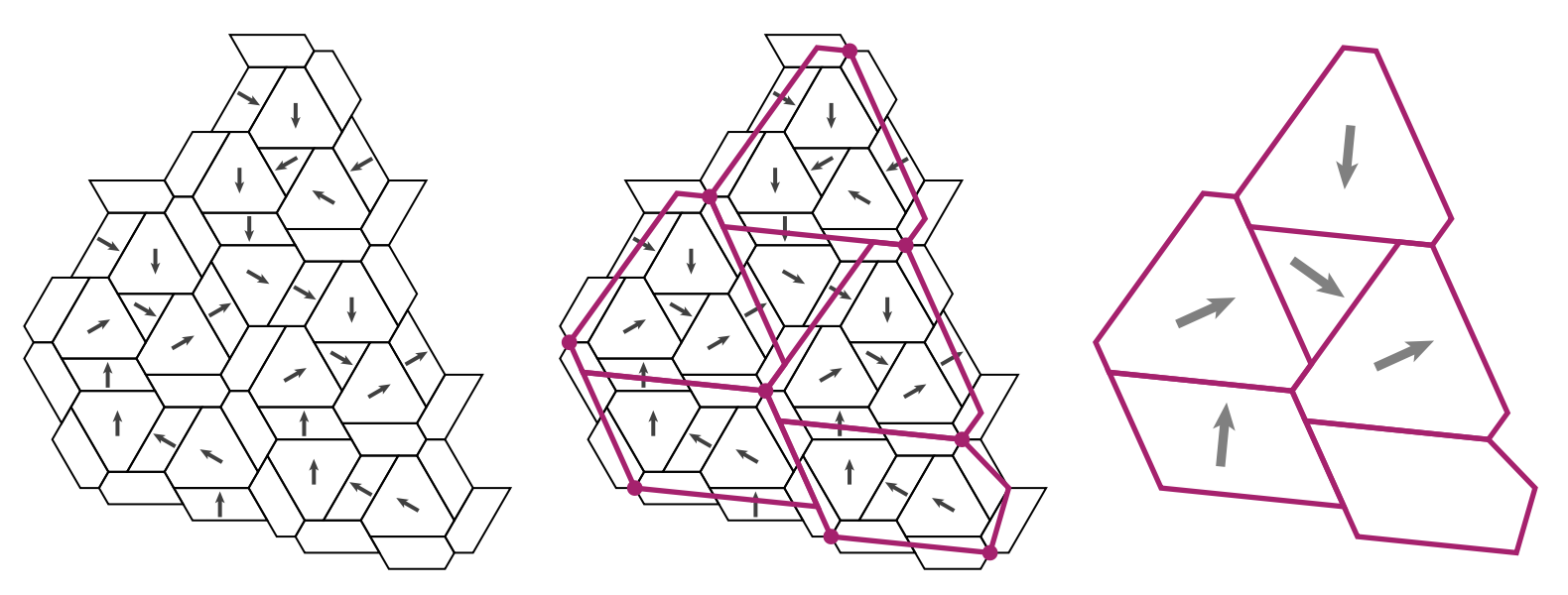

To prove that hats tile the plane, and do so aperiodically, the authors do not apply inflation and deflation directly on the hats, but rather on associated tilings by ‘meta-tiles’ (rough outlines of blocks of hats). To understand these meta-tiles it is best to look at a large patch of hats:

Here, the dark-blue hats are the ‘flipped’ ones, and the thickened outline around the central one gives the boundary of the ’empire’ of a flipped hat, that is, the collection of all forced tiles around it. So, around each flipped hat we find such an empire, possibly with different orientation. Also note that most of the white hats (there are also isolated white hats at the centers of triangles of dark-blue hats) make up ‘lines’ similar to the Conway worms in the case of the Penrose tilings. We can break up these ‘worms’ into ‘propeller-blades’ (gray) and ‘parallelograms’ (white). This gives us four types of blocks, the ‘meta-tiles’:

The empire of a flipped hat consists of an H-block (for Hexagon) made of one dark-blue (flipped) and three light-blue (ordinary) hats, one P-block (for Parallelogram), one F-block (for Fylfot, a propellor blade), and one T-block (for Triangle) for the remaining hat.

The H,T and P blocks have rotational symmetries, whereas the underlying block of hats does not. So we mark the intended orientation of the hats by an arrow, pointing to the side having two or three hat-pieces sticking out.

Any hat-tiling gives us a tiling with the meta-tile pieces H,T,P and F. Conversely, not every tiling by meta-tiles has an underlying hat-tiling, so we have to impose gluing conditions on the H,T,P and F-pieces. We can do this by using the boundary of the underlying hat-block, cutting away and adding hat-parts. Then, any H,T,P and F-tiling satisfying these gluing conditions will come from an underlying hat-tiling.

The idea is now to devise ‘inflation’- and ‘deflation’-rules for the H,T,P and F-pieces. For ‘inflation’ start from a tiling satisfying the gluing (and orientation) conditions, and look for the central points of the propellors (the thick red points in the middle picture).

These points will determine the shape of the larger H,T,P and F-pieces, together with their orientations. The authors provide an applet to see these inflations in action.

Choose your meta-tile (H,T,P or F), then click on ‘Build Supertiles’ a number of times to get larger and larger tilings, and finally unmark the ‘Draw Supertiles’ button to get a hat-tiling.

For ‘deflation’ we can cut up H,T,P and F-pieces into smaller ones as in the pictures below:

Clearly, the hard part is to verify that these ‘inflated’ and ‘deflated’ tilings still satisfy the gluing conditions, so that they will have an underlying hat-tiling with larger (resp. smaller) hats.

This calls for a lengthy case-by-case analysis which is the core-part of the paper and depends on computer-verification.

Once this is verified, aperiodicity follows as in the case of Penrose tilings. Suppose a tiling is preserved under translation by a vector $\vec{v}$. As ‘inflation’ and ‘deflation’ only depend on the direct vicinity of a tile, translation by $\vec{v}$ is also a symmetry of the inflated tiling. Now, iterate this process until the diameter of the large tiles becomes larger than the length of $\vec{v}$ to obtain a contradiction.

Siobhan Roberts wrote a fine article Elusive ‘Einstein’ Solves a Longstanding Math Problem for the NY-times on this einStein.

It would be nice to try this strategy on other symmetric tilings: break the symmetry by gluing together a small number of its orbifolds in such a way that this extended tile (possibly with its reversed image) tile the plane, and find out whether you discovered a new einStein!

Leave a Comment