Today we will explain how curves defined over

$\overline{\mathbb{Q}} $ determine permutation representations

of the carthographic groups. We have seen that any smooth projective

curve $C $ (a Riemann surface) defined over the algebraic

closure $\overline{\mathbb{Q}} $ of the rationals, defines a

_Belyi map_ $\xymatrix{C \ar[rr]^{\pi} & & \mathbb{P}^1} $ which is only ramified over the three points

$\\{ 0,1,\infty \\} $. By this we mean that there are

exactly $d $ points of $C $ lying over any other point

of $\mathbb{P}^1 $ (we call $d $ the degree of

$\pi $) and that the number of points over $~0,1~ $ and

$~\infty $ is smaller than $~d $. To such a map we

associate a _dessin d\’enfant_, a drawing on $C $ linking the

pre-images of $~0 $ and $~1 $ with exactly $d $

edges (the preimages of the open unit-interval). Next, we look at

the preimages of $~0 $ and associate a permutation

$\tau_0 $ of $~d $ letters to it by cycling

counter-clockwise around these preimages and recording the edges we

meet. We repeat this procedure for the preimages of $~1 $ and

get another permutation $~\tau_1 $. That is, we obtain a

subgroup of the symmetric group $ \langle \tau_0,\tau_1

\rangle \subset S_d $ which is called the monodromy

group of the covering $\pi $.

For example, the

dessin on the right is

associated to a degree $8 $ map $\mathbb{P}^1 \rightarrow

\mathbb{P}^1 $ and if we let the black (resp. starred) vertices be

the preimages of $~0 $ (respectively of $~1 $), then the

corresponding partitions are $\tau_0 = (2,3)(1,4,5,6) $

and $\tau_1 = (1,2,3)(5,7,8) $ and the monodromy group

is the alternating group $A_8 $ (use

GAP ).

But wait! The map is also

ramified in $\infty $ so why don\’t we record also a

permutation $\tau_{\infty} $ and are able to compute it from

the dessin? (Note that all three partitions are needed if we want to

reconstruct $C $ from the $~d $ sheets as they encode in

which order the sheets fit together around the preimages). Well,

the monodromy group of a $\mathbb{P}^1 $ covering ramified only

in three points is an epimorphic image of the fundamental

group of the sphere

minus three points $\pi_1(\mathbb{P}^1 – { 0,1,\infty

}) $ That is, the group of all loops beginning and

ending in a basepoint upto homotopy (that is, two such loops are the

same if they can be transformed into each other in a continuous way

while avoiding the three points).

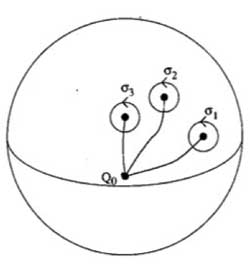

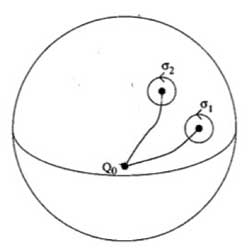

This group is generated by loops

This group is generated by loops

$\sigma_i $ running from the basepoint to nearby the i-th

point, doing a counter-clockwise walk around it and going back to be

basepoint $Q_0 $ and the epimorphism to the monodromy group is given by sending

$\sigma_1 \mapsto \tau_0~\quad~\sigma_2 \mapsto

\tau_1~\quad~\sigma_3 \mapsto \tau_{\infty} $

Now,

these three generators are not independent. In fact, this fundamental

group is

$\pi_1(\mathbb{P}^1 – \\{ 0,1,\infty \\}) =

\langle \sigma_1,\sigma_2,\sigma_3~\mid~\sigma_1 \sigma_2

\sigma_3 = 1 \rangle $

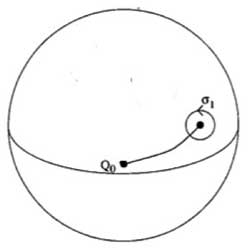

To understand this, let us begin

To understand this, let us begin

with an easier case, that of the sphere minus one point. The fundamental group of the plane minus one point is

$~\mathbb{Z} $ as it encodes how many times we walk around the

point. However, on the sphere the situation is different as we can make

our walk around the point longer and longer until the whole walk is done

at the backside of the sphere and then we can just contract our walk to

the basepoint. So, there is just one type of walk on a sphere minus one

point (upto homotopy) whence this fundamental group is trivial. Next,

let us consider the sphere minus two points

Repeat the foregoing to the walk $\sigma_2 $, that

is, strech the upper part of the circular tour all over the backside of

the sphere and then we see that we can move it to fit with the walk

$\sigma_1$ BUT for the orientation of the walk! That is, if we do this

modified walk $\sigma_1 \sigma_2^{\’} $ we just made the

trivial walk. So, this fundamental group is $\langle

\sigma_1,\sigma_2~\mid~\sigma_1 \sigma_2 = 1 \rangle =

\mathbb{Z} $ This is also the proof of the above claim. For,

we can modify the third walk $\sigma_3 $ continuously so that

it becomes the walk $\sigma_1 \sigma_2 $ but

with the reversed orientation ! As $\sigma_3 =

(\sigma_1 \sigma_2)^{-1} $ this allows us to compute the

\’missing\’ permutation $\tau_{\infty} = (\tau_0

\tau_1)^{-1} $ In the example above, we obtain

$\tau_{\infty}= (1,2,6,5,8,7,4)(3) $ so it has two cycles

corresponding to the fact that the dessin has two regions (remember we

should draw ths on the sphere) : the head and the outer-region. Hence,

the pre-images of $\infty$ correspond to the different regions of the

dessin on the curve $C $. For another example,

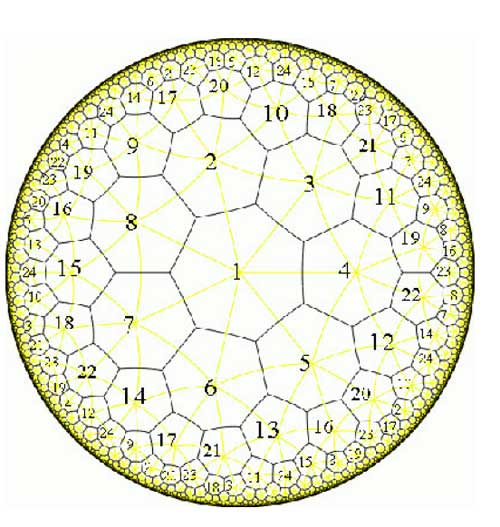

consider the degree 168 map

$K \rightarrow \mathbb{P}^1 $

which is the modified orbit map for the action of

$PSL_2(\mathbb{F}_7) $ on the Klein quartic.

The corresponding dessin is the heptagonal construction of the Klein

quartic

Here, the pre-images of 1 correspond to the midpoints of the

84 edges of the polytope whereas the pre-images of 0 correspond to the

56 vertices. We can label the 168 half-edges by numbers such that

$\tau_0 $ and $\tau_1 $ are the standard generators b

resp. a of the 168-dimensional regular representation (see the atlas

page ).

Calculating with GAP the element $\tau_{\infty} = (\tau_0

\tau_1)^{-1} = (ba)^{-1} $ one finds that this permutation

consists of 24 cycles of length 7, so again, the pre-images of

$\infty $ lie one in each of the 24 heptagonal regions of the

Klein quartic. Now, we are in a position to relate curves defined

over $\overline{Q} $ via their Belyi-maps and corresponding

dessins to Grothendiecks carthographic groups $\Gamma(2) $,

$\Gamma_0(2) $ and $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $. The

dessin gives a permutation representation of the monodromy group and

because the fundamental group of the sphere minus three

points $\pi_1(\mathbb{P}^1 – \\{ 0,1,\infty \\}) =

\langle \sigma_1,\sigma_2,\sigma_3~\mid~\sigma_1 \sigma_2

\sigma_3 = 1 \rangle = \langle \sigma_1,\sigma_2

\rangle $ is the free group op two generators, we see that

any dessin determines a permutation representation of the congruence

subgroup $\Gamma(2) $ (see this

post where we proved that this

group is free). A clean dessin is one for which one type of

vertex has all its valancies (the number of edges in the dessin meeting

the vertex) equal to one or two. (for example, the pre-images of 1 in

the Klein quartic-dessin or the pre-images of 1 in the monsieur Mathieu

example ) The corresponding

permutation $\tau_1 $ then consists of 2-cycles and hence the

monodromy group gives a permutation representation of the free

product $C_{\infty} \ast C_2 =

\Gamma_0(2) $ Finally, a clean dessin is said to be a

quilt dessin if also the other type of vertex has all its valancies

equal to one or three (as in the Klein quartic or Mathieu examples).

Then, the corresponding permutation has order 3 and for these

quilt-dessins the monodromy group gives a permutation representation of

the free product $C_2 \ast C_3 =

PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ Next time we will see how this lead

Grothendieck to his anabelian geometric approach to the absolute Galois

group.