Before ChatGPT, the hype among productivity boosters was a PKMs or Personal knowledge management system.

It gained popularity through Tiago Forte’s book ‘Building a second brain’, and (for academics perhaps a more useful read) ‘How to take smart notes’ by Sönke Ahrens.

These books promote new techniques for note-taking (and for storing these notes) such as the PARA-method, the CODE-system, and Zettelkasten.

Unmistakable Creative has some posts on the principles behing the ‘second brain’ approach.

Your brain isn’t like a hard drive or a dropbox, where information is stored in folders and subfolders. None of our thoughts or ideas exist in isolation. Information is organized in a series of non-linear associative networks in the brain.

Networked thinking is not just a more efficient way to organize information. It frees your brain to do what it does best: Imagine, invent, innovate, and create. The less you have to remember where information is, the more you can use it to summarize that information and turn knowledge into action.

and

A network has no “correct” orientation and thus no bottom and no top. Each individual, or “node,” in a network functions autonomously, negotiating its own relationships and coalescing into groups. Examples of networks include a flock of birds, the World Wide Web, and the social ties in a neighborhood. Networks are inherently “bottom-up” in that the structure emerges organically from small interactions without direction from a central authority.

-Tiago Forte, Tagging for Personal Knowledge Management

There are several apps you can use to start building your second brain, the more popular seem to be Roam Research, LogSeq, and Obsidian.

These systems allow you to store, link and manipulate a large collection of notes, query them as a database, modify them in various ways via plugins or scripts, and navigate the network created via graph-views.

Exactly the kind of things we need to modify the simple system from the shape of languages-post into a proper topos of the unconscious.

I’ve been playing around with Obsidian which I like because it has good LaTeX plugins, powerful database tools via the Dataview plugin, and one can execute codeblocks within notes in almost any programming language (python, haskell, lean, Mathematica, ruby, javascript, R, …).

Most of all it has a vibrant community of users, an excellent forum, and a well-documented Obsidian hub.

There’s just one problem, I’m a terrible note-taker, so how can I begin to load my ‘second brain’?

Obsidian has several plugins to import data, such as your Kindle highlights, your Twitter feed, your Readwise-data, and many others, but having been too lazy in the past, I cannot use any of them.

In fact, the only useful collection of notes I have are my blog-posts. So, I’ve uploaded NeverEndingBooks into Obsidian, one note per post (admittedly, not very Zettelkasten-like), half a million words in total.

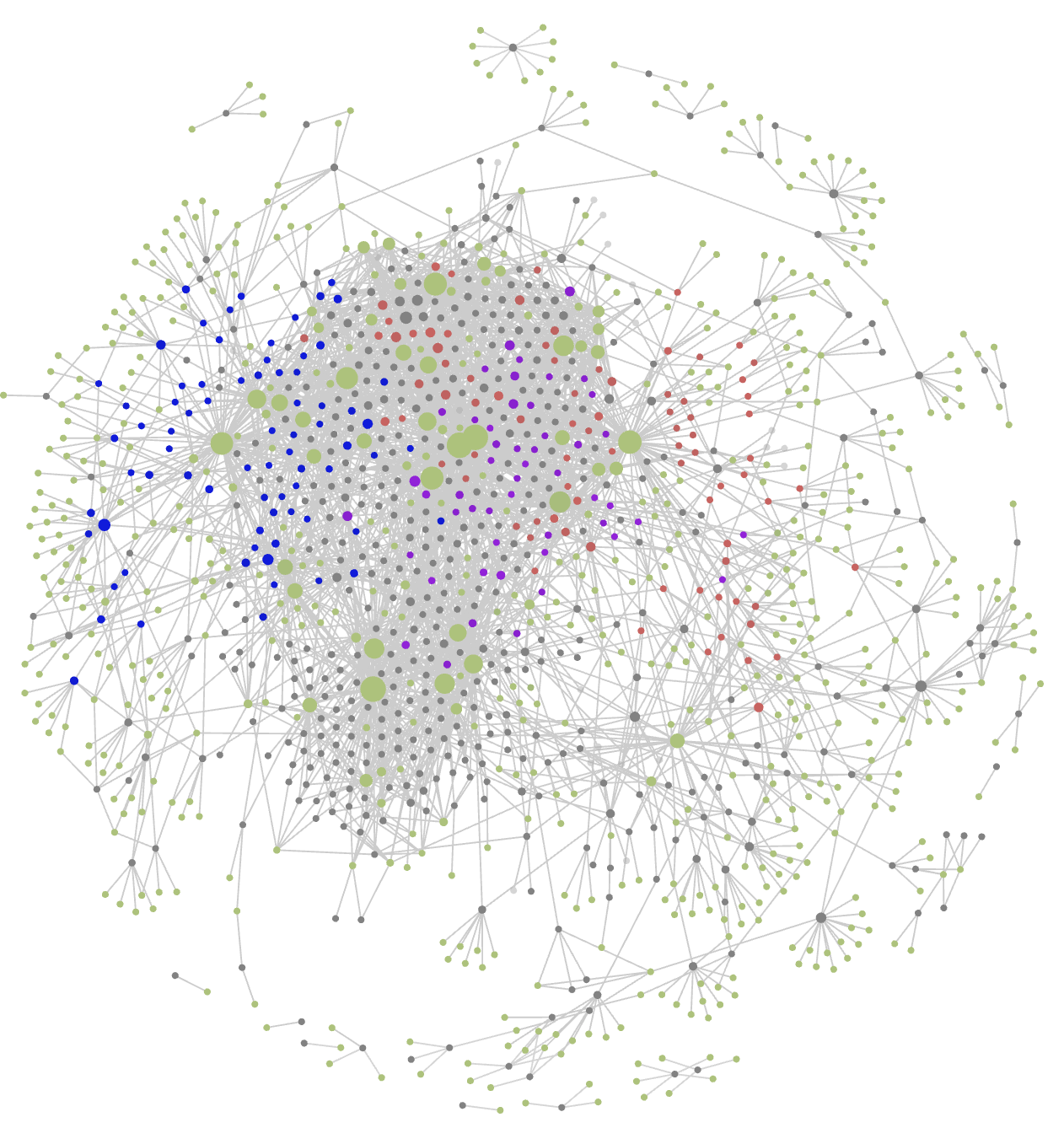

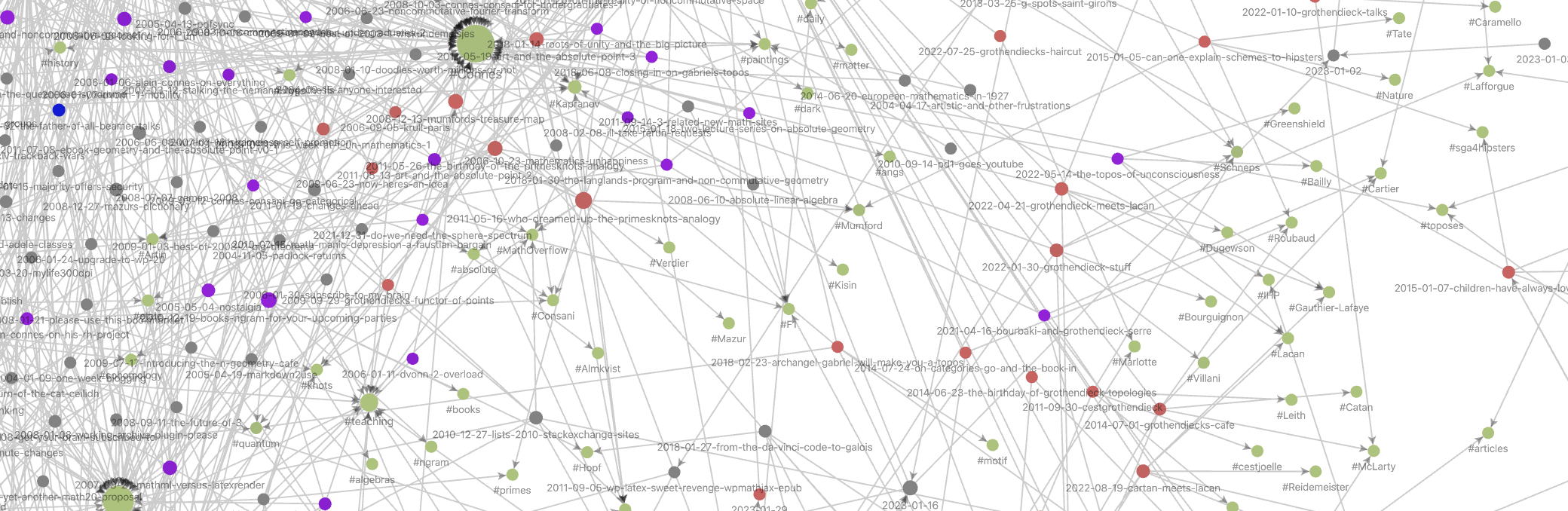

Fortunately, I did tag most of these posts at the time. Together with other meta-data this results in the Graph view below (under ‘Files’ toggled tags, under ‘Groups’ three tag-colours, and under ‘Display’ toggled arrows). One can add colour-groups based on tags or other information (here, red dots are posts tagged ‘Grothendieck’, the blue ones are tagged ‘Conway’, the purple ones tagged ‘Connes’, just for the sake of illustration). In Obsidian you can zoom into this graph, place a pointer on a node to highlight the connecting dots, and much more.

Because I tend to forget such things, and as it may be useful to other people running a WordPress-blog making heavy use of MathJax, here’s the procedure I followed:

1. Follow the instructions from Convert wordpress articles to markdown.

- Export your WordPress posts to XML

- Install Node.js

- Run the wordpress-export-to-markdown script

In the wizard I’ve opted to go only for yearly folders, to prefix posts with the date, and to save all images.

2. This gives you a directory with one folder per year containing markdown versions of your posts, and in each year-folder a subfolder ‘img’ containing all images.

Turn this directory into an Obsidian-vault by opening Obsidian, click on the ‘open another vault’ icon (third from bottom-left), select ‘Open folder as vault’ and navigate to your directory.

3. You will notice that most of your LaTeX cannot be parsed because during the markdown-process backslashes are treaded as special character, resulting in two backslashes for every LaTeX-command…

A remark before trying to solve this: another option might be to use the wordpress-to-hugo-exporter, resulting in clean LaTeX, but lacking the possibility to opt for yearly-folders (it dumps all posts into one folder), and it makes a mess of the image-files.

4. So, we will need to do a lot of search&replaces in all files, and need a convenient tool for this.

First option was the Sublime Text app, which is free and does the search&replaces quickly. The problem is that you have to save each of the files, one at a time! This may take hours.

I’ve done it using the Search and Replace app (3$) which allows you to make several searches/replaces at the same time (I messed up LaTeX code in previous exports, so needed to do many more changes). It warns you that it is dangerous to replace strings in all files (which is the reason why Sublime Text makes it difficult), you can ignore it, but only after you put the ‘img’ folders away in a safe place. Otherwise it will also try to make the changes to these files, recognise that they are not text-files, and drop them altogether…

That’s it.

I now have a backup network-version of this blog.

As we mentioned in the previous post a first attempt to construct the ‘topos of the unconscious’ might be to start with a collection of notes (the ‘conscious’) and work on the semantics of text-snippets to unravel (a part of) the unconscious underpinning of these notes. We also mentioned that the poset-structure in that post should be replaced by a more involved network structure.

What interests me most is whether such an approach might be doable ‘in practice’, and Obsidian looks like the perfect tool to try this out.

What we need is a sufficiently large set of notes, of independent interest, to inject into Obsidian. The more meta it is, the better…

(tbc)

Previously in this series:

Next:

Leave a Comment