We will see later that the cyclic subgroup $T_6 \subset \mathbb{F}_{p^6}^* $ is a 2-dimensional torus.

We will see later that the cyclic subgroup $T_6 \subset \mathbb{F}_{p^6}^* $ is a 2-dimensional torus.

Take a finite set of polynomials $f_i(x_1,\ldots,x_k) \in \mathbb{F}_p[x_1,\ldots,x_k] $ and consider for every fieldextension $\mathbb{F}_p \subset \mathbb{F}_q $ the set of all k-tuples satisfying all these polynomials and call this set

$X(\mathbb{F}_q) = { (a_1,\ldots,a_k) \in \mathbb{F}_q^k~:~f_i(a_1,\ldots,a_k) = 0~\forall i } $

Then, $T_6 $ being a 2-dimensional torus roughly means that we can find a system of polynomials such that

$T_6 = X(\mathbb{F}_p) $ and over the algebraic closure $\overline{\mathbb{F}}_p $ we have $X(\overline{\mathbb{F}}_p) = \overline{\mathbb{F}}_p^* \times \overline{\mathbb{F}}_p^* $ and $T_6 $ is a subgroup of this product group.

It is known that all 2-dimensional tori are rational. In particular, this means that we can write down maps defined by rational functions (fractions of polynomials) $f~:~T_6 \rightarrow \mathbb{F}_p \times \mathbb{F}_p $ and $j~:~\mathbb{F}_p \times \mathbb{F}_p \rightarrow T_6 $ which define a bijection between the points where f and j are defined (that is, possibly excluding zeroes of polynomials appearing in denumerators in the definition of the maps f or j). But then, we can use to map f to represent ‘most’ elements of $T_6 $ by just 2 pits, exactly as in the XTR-system.

Making the rational maps f and j explicit and checking where they are ill-defined is precisely what Karl Rubin and Alice Silverberg did in their CEILIDH-system. The acronym CEILIDH (which they like us to pronounce as ‘cayley’) stands for Compact Efficient Improves on LUC, Improves on Diffie-Hellman…

A Cailidh is a Scots Gaelic word meaning ‘visit’ and stands for a ‘traditional Scottish gathering’.

Between 1997 and 2001 the Scottish ceilidh grew in popularity again amongst youths. Since then a subculture in some Scottish cities has evolved where some people attend ceilidhs on a regular basis and at the ceilidh they find out from the other dancers when and where the next ceilidh will be.

Privately organised ceilidhs are now extremely common, where bands are hired, usually for evening entertainment for a wedding, birthday party or other celebratory event. These bands vary in size, although are commonly made up of between 2 and 6 players. The appeal of the Scottish ceilidh is by no means limited to the younger generation, and dances vary in speed and complexity in order to accommodate most age groups and levels of ability.

Anyway, let us give the details of the Rubin-Silverberg approach. Take a large prime number p congruent to 2,6,7 or 11 modulo 13 and such that $\Phi_6(p)=p^2-p+1 $ is again a prime number. Then, if $\zeta $ is a 13-th root of unity we have that $\mathbb{F}_{p^{12}} = \mathbb{F}_p(\zeta) $. Consider the elements

$\begin{cases} z = \zeta + \zeta^{-1} \\ y = \zeta+\zeta^{-1}+\zeta^5+\zeta^{-5} \end{cases} $

Then, for every $~(u,v) \in \mathbb{F}_p \times \mathbb{F}_p $ define the map $j $ to $T_6 $ by

$j(u,v) = \frac{r-s \sqrt{13}}{r+s \sqrt{13}} \in T_6 $

and one can verify that this is indeed an element of $T_6 $ provided we take

$\begin{cases} r = (3(u^2+v^2)+7uv+34u+18v+40)y^2+26uy-(21u(3+v)+9(u^2+v^2)+28v+42) \\

s = 3(u^2+v^2)+7uv+21u+18v+14 \end{cases} $

Conversely, for $t \in T_6 $ write $t=a + b \sqrt{13} $ using the basis $\mathbb{F}_{p^6} = \mathbb{F}_{p^3}1 \oplus \mathbb{F}_{p^3} \sqrt{13} $, so $a,b \in \mathbb{F}_{p^3} $ and consequently write

$\frac{1+a}{b} = w y^2 + u (y + \frac{y^2}{2}) + v $

with $u,v,w \in \mathbb{F}_p $ using the basis ${ y^2.y+\frac{y^2}{2},1 } $ of $\mathbb{F}_{p^3}/\mathbb{F}_p $. Okay, then the invers of $j $ iis the map $f~:~T_6 \rightarrow \mathbb{F}_p \times \mathbb{F}_p $ given by

$f(t) = (\frac{u}{w+1},\frac{v-3}{w+1}) $

and it takes some effort to show that f and j are indeed each other inverses, that j is defined on all points of $\mathbb{F}_p \times \mathbb{F}_p $ and that f is defined everywhere except at the two points

${ 1,-2z^5+6z^3-4z-1 } \subset T_6 $. Therefore, as long as we avoid these two points in our Diffie-Hellman key exchange, we can perform it using just $2=\phi(6) $ pits : I will send you $f(g^a) $ allowing you to compute our shared key $f(g^{ab}) $ or $g^{ab} $ from my data and your secret number b.

But, where’s the cat in all of this? Unfortunately, the cat is dead…

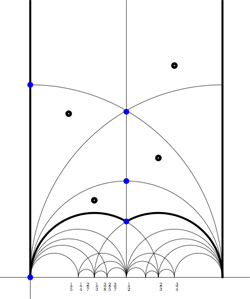

we get the special polygonal region bounded by the thick edges, the vertical edges are identified as are the two bottom edges. Hence, this fundamental domain has 6 vertices (the 5 blue dots and the point at $i \infty $) and 8 hyperbolic triangles (4 colored black, indicated by a black dot, and 4 white ones).

we get the special polygonal region bounded by the thick edges, the vertical edges are identified as are the two bottom edges. Hence, this fundamental domain has 6 vertices (the 5 blue dots and the point at $i \infty $) and 8 hyperbolic triangles (4 colored black, indicated by a black dot, and 4 white ones).