Guest post by Fred Van Oystaeyen.

Guest post by Fred Van Oystaeyen.

In my book “Virtual Topology and Functorial Geometry” (Taylor and Francis, 2009) I proposed a noncommutative version of space-time ; it is a toy model, but mathematically correct and I included a few philosophical remarks about : “What if reality is noncommutative ?”.

I want to add a few ideas about how “strange” ideas in quantum mechanics all fit naturally in the noncommutative world. First let us talk about noncommutative geometry in an intuitive way.

Then noncommutative space may be thought of as a set of noncommutative places but these noncommutative places need not be sets, in particular they are not sets of points. There is a noncommutative join $\vee$ and a noncommutative intersection $\wedge$, and they satify the axioms (very natural ones) of a noncommutative topology.

The non-commutativity is characterized by the existence of non $\wedge$-idempotent places, i.e. places with a nontrivial self intersection. This allows the $\wedge$ to be noncommutative. From algebraic geometric it follows that one may be interested to let $\vee$ be an abelian operation (hence defining a virtual topology) so let us assume this from hereon.

The set of $\wedge$-idempotent noncommutative-places forms the “commutative shadow” of the noncommutative space; it has operations $\vee$ and $\mathop{\wedge}\limits_{\bullet}$ which are abelian and $\sigma \mathop{\wedge}\limits_{\bullet}\tau$ may be thought of as the largest $\wedge$-idempotent smaller than $\sigma$ and $\tau$ in the partial ordering of the noncommutative space.

The $\wedge$-idempotent noncommutative places are sets in a commutative topology and these are the observable places in the noncommutative space. In the book I present a dynamic (time !) model allowing further elaboration on the noncommutative space but for now let us stick to the intuitive model and assume that space is in fact noncommutative with commutative shadow built upon our space time of physics.

In fact all observations, measurings and predictions made in physics are not about reality but about our observations of reality, so it may be an eternal fact that our observations of reality are described in our brains by commutative methods. Nevertheless we can observe effect of objects existing at noncommutative places in “neighboring” $\wedge$-idempotents sets or observable places.

First if an object exists at a noncommutative place it also exists at all subplaces (a harmless assumption not really essential for the rest). So if there is a noncommutative place, where some object exists, parts of this object may be observed at idempotent subplaces of the noncommutative place. These may even be disjoint in the commutative shadow, not “too far apart” as one object exists on the total noncommutative space.

Since only a part of the noncommutative object is observed on the $\wedge$-idempotent subplace it is not clear that one may actually recognize the observations at different commutative places as belonging to the same noncommutative object. Once one observes one observable place that object seems to exist only on that (commutative) place. Hence a quantum particle can be thought of as existing on several “places” but once observed it looks like it only exists there. This is a first natural phenomenon reflecting “strange” quantum mechanical principles.

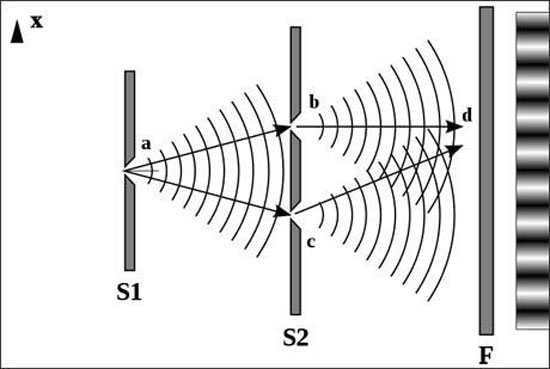

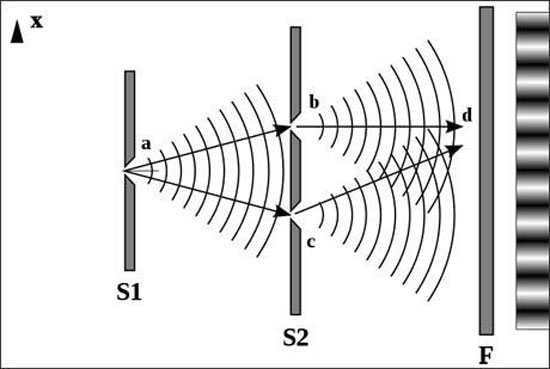

Secondly let us look at the double slit experiment. The slits correspond to commutative places $\sigma_1$ and $\sigma_2$ and $\sigma_1 \mathop{\wedge}\limits_{\bullet}\sigma_2=\emptyset$, however in the noncommutative world $\sigma_1\wedge\sigma_2$ need not be empty, only it has no $\wedge$-idempotent subplaces !

Therefore if a photon is defined on a noncommutative place with “light”-effect on observable places “near enough” to it (in a neighborhood small enough to have an observable effect say) then the photon may pass though both slits without splitting or without splitting reality (parallel universes) but just moving into the noncommutative space inside $\sigma_1$ and $\sigma_2$ !

The observable effect at the slits will appear in commutative places near enough (for example, intersecting) to $\sigma_1$ or to $\sigma_2$. As the photon moves on, observable effects will appear in commutative places intersecting the one near to $\sigma_1$ or the one near to $\sigma_2$ and these may themselves have nonempty intersections.

At the moment the effect via $\sigma_1$ interacts with the effect via $\sigma_2$. As the photon progresses in its observed direction other $\wedge$-idempotents showing observable effects may meet and so several interactions between observable effects (via $\sigma_1$ and $\sigma_2$) build a picture of interference.

The symmetry of this picture actually suggests a symmetric arrangement of commutative places around a noncommutative place. So the noncommutativity of space may explain this phenomenon without holographic principle or parallel universes.

In a similar way dark mass may well be mass existing in a non-observable noncommutative place (i.e. containing no observable places). If a lot of mass is in a non-observable noncommutative place its gravity may pull matter from surrounding observable places into the noncommutative place and this may explain black holes. All kinds of problems relating to black holes may have natural non commutative solutions, e.g. information may pass from observable places to noncommutative places and is not lost, only non-observable.

In fact is the definition of information not depending on the nature and capability of the recipient ? There are many philosophically interesting ramifications of these ideas, for example every chemical or neurochemical activity should also be placed in the noncommutative space.

In the book I mentioned how “free will” could be a noncommutative space aspect of the brain activity. I also mention a possible relations with string theory. I am not a specialist in all these things but now I reached the point that I “feel” noncommutative space is a better approximation of the reality and one should investigate it further.

Mathblogging.org is a recent initiative and may well become the default starting place to check on the status of the mathematical blogosphere.

Mathblogging.org is a recent initiative and may well become the default starting place to check on the status of the mathematical blogosphere. Guest post by

Guest post by