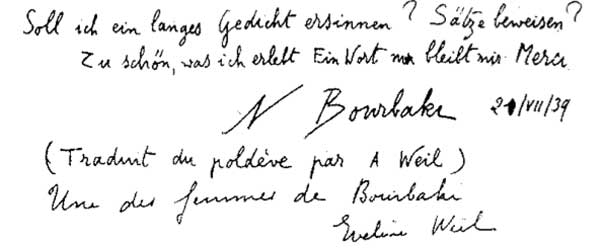

Last time we’ve seen that on June 3rd 1939, the very day of the Bourbaki wedding, Malraux’ movie ‘L’espoir’ had its first (private) viewing, and we mused whether Weil’s wedding card was a coded invitation to that event.

But, there’s another plausible explanation why the Bourbaki wedding might have been scheduled for June 3rd : it was intended to be a copy-cat Royal Wedding…

The media-hype surrounding the wedding of Prince William to Pippa’s sister led to a hausse in newspaper articles on iconic royal weddings of the past.

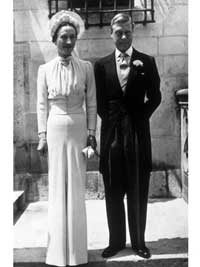

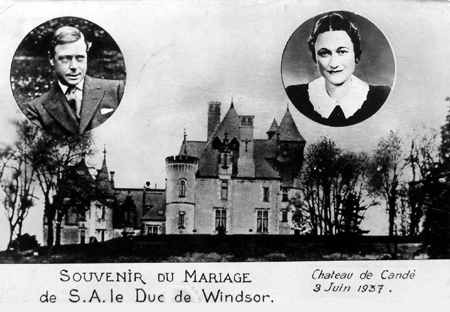

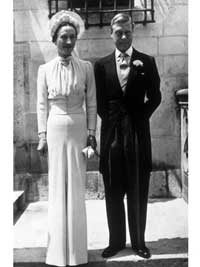

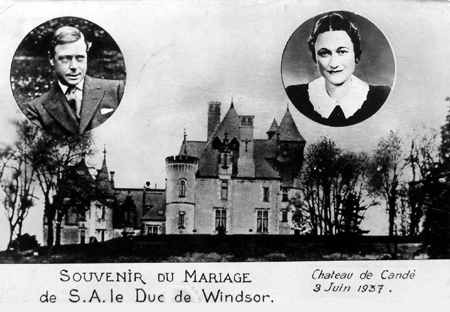

One of these, the marriage of Edward VIII, Duke of Windsor and Wallis Warfield Spencer Simpson, was held on June 3rd 1937 : “This was the scandal of the century, as far as royal weddings go. Edward VIII had just abdicated six months before in order to marry an American twice-divorced commoner. The British Establishment at the time would not allow Edward VIII to stay on the throne and marry this woman (the British Monarch is also the head of the Church of England), so Edward chose love over duty and fled to France to await the finalization of his beloved’s divorce. They were married in a private, civil ceremony, which the Royal Family boycotted.”

One of these, the marriage of Edward VIII, Duke of Windsor and Wallis Warfield Spencer Simpson, was held on June 3rd 1937 : “This was the scandal of the century, as far as royal weddings go. Edward VIII had just abdicated six months before in order to marry an American twice-divorced commoner. The British Establishment at the time would not allow Edward VIII to stay on the throne and marry this woman (the British Monarch is also the head of the Church of England), so Edward chose love over duty and fled to France to await the finalization of his beloved’s divorce. They were married in a private, civil ceremony, which the Royal Family boycotted.”

But, what does this wedding have to do with Bourbaki?

For starters, remember that the wedding-card-canular was concocted in the spring of 1939 in Cambridge, England. So, if Weil and his Anglo-American associates needed a common wedding-example, the Edward-Wallis case surely would spring to mind. One might even wonder about the transposed symmetry : a Royal (Betti, whose father is from the Royal Poldavian Academy), marrying an American (Stanislas Pondiczery).

Even Andre Weil must have watched this wedding with interest (perhaps even sympathy). He too had to wait a considerable amount of time for Eveline’s divorce (see this post) to finalize, so that they could marry on october 30th 1937, just a few months after Edward & Wallis.

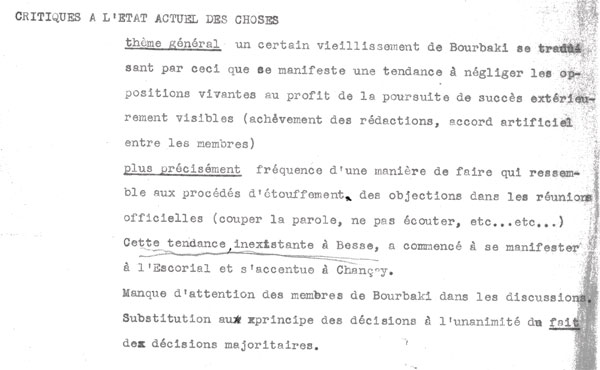

But, there’s more. The royal wedding took place at the Chateau de Cande, just south of Tours (the A on the google-map below). Now, remember that the 2nd Bourbaki congress was held at the Chevalley family-property in Chancay (see the Escorial post) a bit to the north-east of Tours (the marker on the map). As this conference took place only a month after the Royal Wedding (from 10th till 20th of July 1937), the event surely must have been the talk of the town.

Early on, we concluded that the Bourbaki-Petard wedding took place at 12 o’clock (‘a l’heure habituelle’). So did the Edward-Wallis wedding. More precisely, the civil ceremony began at 11.47 and the local mayor had to come to the castle for the occasion, and, afterwards the couple went into the music-room, which was converted into an Anglican chapel for the day, at precisely 12 o’clock.

The emphasis on the musical organ in the Bourbaki wedding-invitation allowed us to identify the identity of ‘Monsieur Modulo’ to be Olivier Messiaen as well as that of the wedding church. Now, the Chateau de Cande also houses an impressive organ, the Skinner opus 718 organ.

The emphasis on the musical organ in the Bourbaki wedding-invitation allowed us to identify the identity of ‘Monsieur Modulo’ to be Olivier Messiaen as well as that of the wedding church. Now, the Chateau de Cande also houses an impressive organ, the Skinner opus 718 organ.

For the wedding ceremony, Edward and Wallis hired the services of one of the most renowned French organists at the time : Marcel Dupre who was since 1906 Widor’s assistent, and, from 1934 resident organist in the Saint-Sulpice church in Paris. Perhaps more telling for our story is that Dupre was, apart from Paul Dukas, the most influential teacher of Olivier Messiaen.

On June 3rd, 1937 Dupre performed the following pieces. During the civil ceremony, an extract from the 29e Bach cantate, canon in re-minor by Schumann and the prelude of the fugue in do-minor of himself. When the couple entered the music room he played the march of the Judas Macchabee oratorium of Handel and the cortege by himself. During the religious ceremony he performed his own choral, adagium in mi-minor by Cesar Franck, the traditional ‘Oh Perfect Love’, the Jesus-choral by Bach and the toccata of the 5th symphony of Widor. Compare this level of detail to the minimal musical hint given in the Bourbaki wedding-invitation

“Assistent Simplexe de la Grassmannienne (lemmas chantees par la Scholia Cartanorum)”

This is one of the easier riddles to solve. The ‘simplicial assistent of the Grassmannian’ is of course Hermann Schubert (Schubert cell-decomposition of Grassmannians). But, the composer Franz Schubert only left us one organ-composition : the Fugue in E-minor.

I have tried hard to get hold of a copy of the official invitation for the Edward-Wallis wedding, but failed miserably. There must be quite a few of them still out there, of the 300 invited people only 16 showed up… You can watch a video newsreel film of the wedding.

As Claude Chevalley’s father had an impressive diplomatic career behind him and lived in the neighborhood, he might have been invited, and, perhaps the (unused) invitation was lying around at the time of the second Bourbaki-congress in Chancay,just one month after the Edward-Wallis wedding…

One of these, the marriage of

One of these, the marriage of

The emphasis on the musical organ in the Bourbaki wedding-invitation

The emphasis on the musical organ in the Bourbaki wedding-invitation