You better subscribe to the French newspaper Liberation if you’re interested in the latest whereabouts of Grothendieck’s ‘gribouillis’. And even then it is hard to turn this info into a consistent tale. A futile attempt…

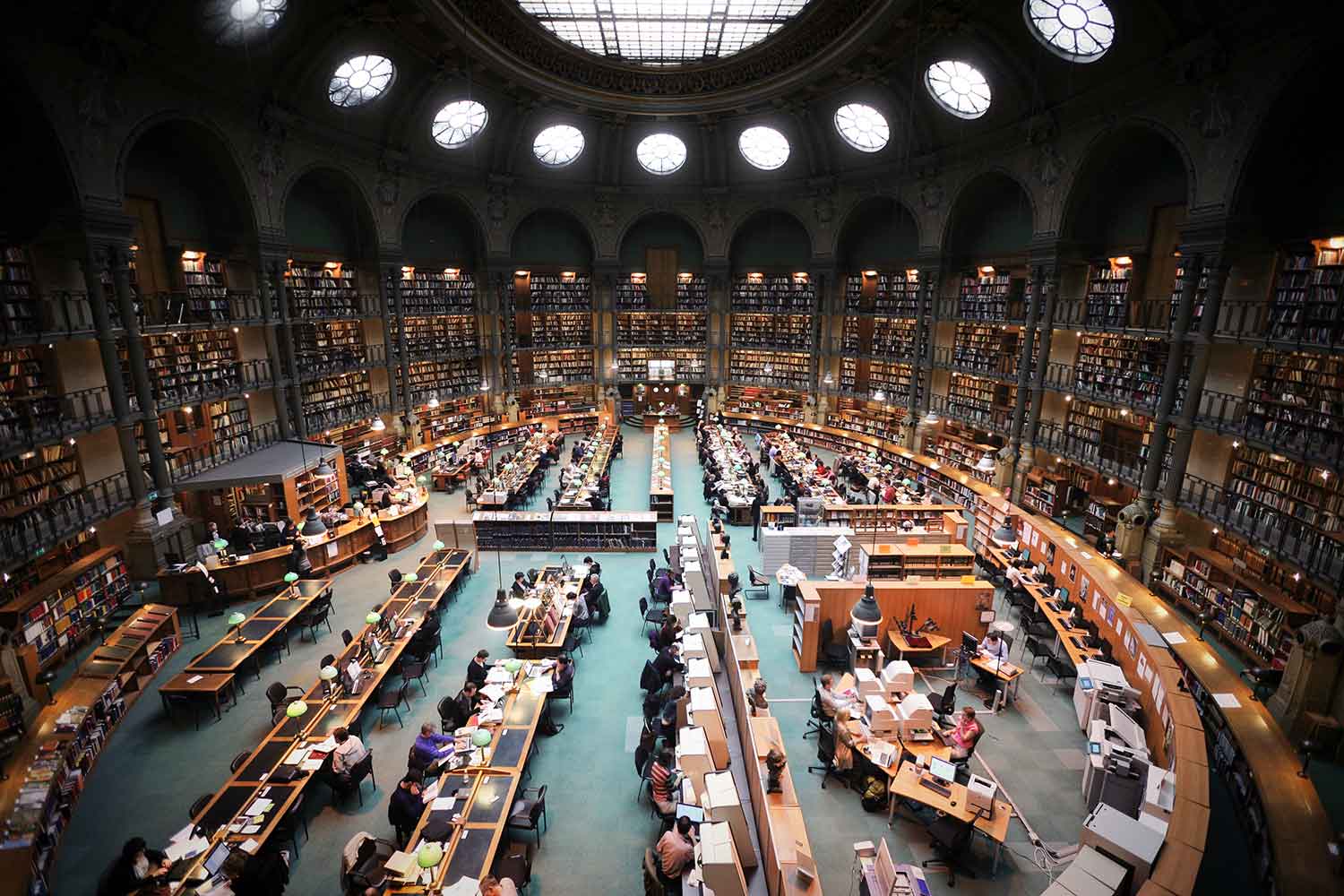

“In the Bibliotheque Nationale de France?”

A year ago it all seemed pretty straightforward. Georges Maltsiniotis gave a talk at the Grothendieck conference on a small part of the 65.000 pages discovered after Grothendieck’s death in Lasserre.

He said that Grothendieck’s family has handed over all non-family related material to the Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

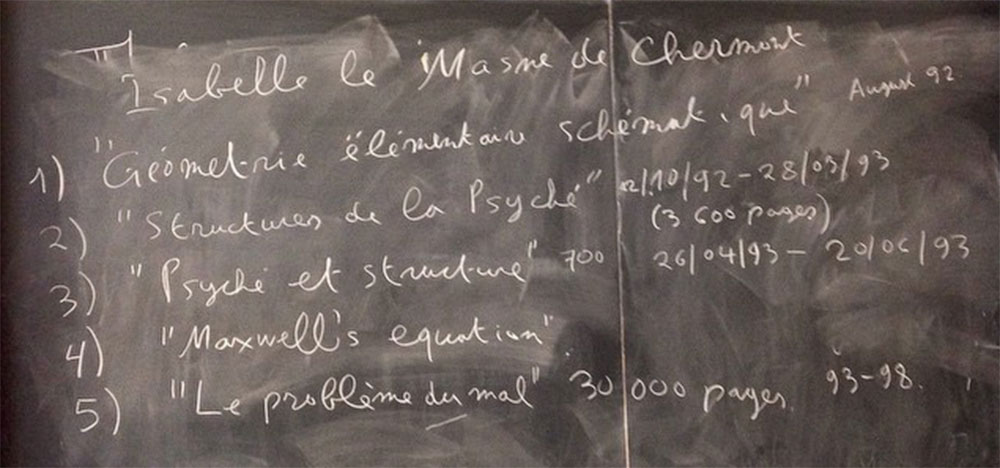

Maltsiniotis insisted that the BNF wants to make these notes available to the academic community, after they made an inventory (which may take some time) and mentioned that the person responsible at the BNF is Isabelle le Masme de Chermont.

A year later there’s still no sign of the Lasserre papers in their database.

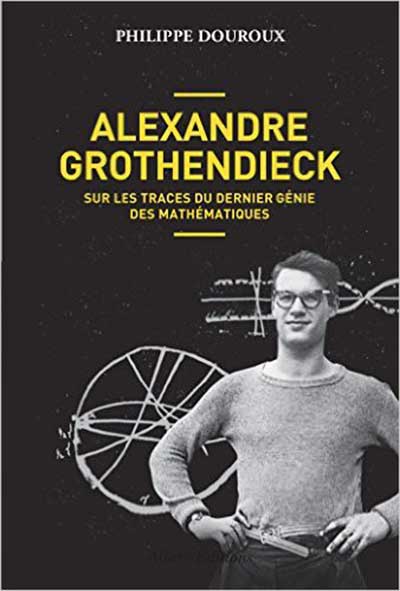

Earlier this year, Liberation-jounalist Philippe Douroux, published a book on Grothendieck’s life: “Alexandre Grothendieck, sur les traces du dernier genie des mathematiques”.

In this book, and in follow-up articles in Liberation, he follows the trail of Grothendieck’s gribouillis and suggests that we’d better look in stranger places, such as a police station or even a botanical institute…

“In a Parisian police station?”

From chapter 46 of Douroux’ book:

On November 13th 2015, while the terrorist-attacks on the Bataclan and elsewhere were going on, a Mercedes break with on board Alexandre Jr. Grothendieck and Jean-Bernard, a librarian specialised in ancient writings, was approaching Paris from Lasserre. On board: 5 metallic cases, 2 red ones, 1 green and 2 blues.

At about 2 into the night they arrived at the ‘commissariat du Police’ of the 6th arrondissement. Jean-Bernard pushed open a heavy blue carriage porch, crossed the courtyard opened a second door and then a third one and delivered the cases.

Comparing this description with the image above from google maps, the Lasserre boxes might be in the white building behind the police station.

I have no clue what the function of this building is, or why the boxes were delivered at that place, not at all close to the Bibliotheque Nationale.

As to why they are not at the BNF, this is probably a question of money.

Before the BNF can accept a legacy, French law says they have to agree on its value with the family. Their initial estimate was ridiculously low: 45.000 Euros or less than one Euro a page. In a similar case, the archives of Michel Foucault, a former professor at the College de France, were acquired by the BNF for no less than 4.800.000 Euro.

“At the botanical institute in Montpellier?”

The mysterious white building in Paris is the best guess to hold the 65.000 pages Grothendieck wrote in Lasserre.

However, there are also the 20.000 pages of the Mormoiron gribouillis, consisting of 5 boxes (Pamper-boxes it is said) rescued by Malgoire in 1991 from Grothendieck’s bonfire.

In 2010, after Grothendieck’s letter that his work should be destroyed, Malgoire donated the Pamper-boxes to the university of Montpellier. The university put them in solid archive boxes and placed them in the Botanical Institute.

As Grothendieck donated these writings to Malgoire, who donated them in turn to his university, the University of Montpellier claimed to own the Mormoiron-gribouillis, and started a silly legal battle with Grothendieck’s children.

On May 3rd the children won, and the documents should have been handed over to the family by mid July 2016. The intention was that they would join the Lasserre notes in Paris.

Mid June, however, the region of Languedoc-Roussillon gave the University of Montpellier 57.000 Euro so that the Grothendieck-notes could be scanned and archived. Probably, a delaying tactic.

So, my best guess is that the Mormoiron gribouillis are still in Montpellier.

Leave a Comment

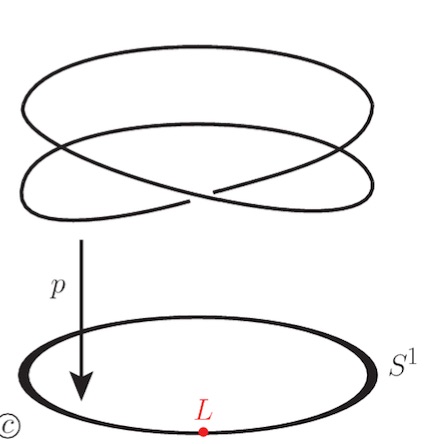

Let’s look at a finite field $\mathbb{F}_p$. Here, Galois extensions of $\mathbb{F}_p$ (and there is just one such extension of degree $n$, upto isomorphism) correspond to connected etale covers of the circle $S^1$.

Let’s look at a finite field $\mathbb{F}_p$. Here, Galois extensions of $\mathbb{F}_p$ (and there is just one such extension of degree $n$, upto isomorphism) correspond to connected etale covers of the circle $S^1$.