It has been many, many years since I’ve last visited the Bourbaki Archives.

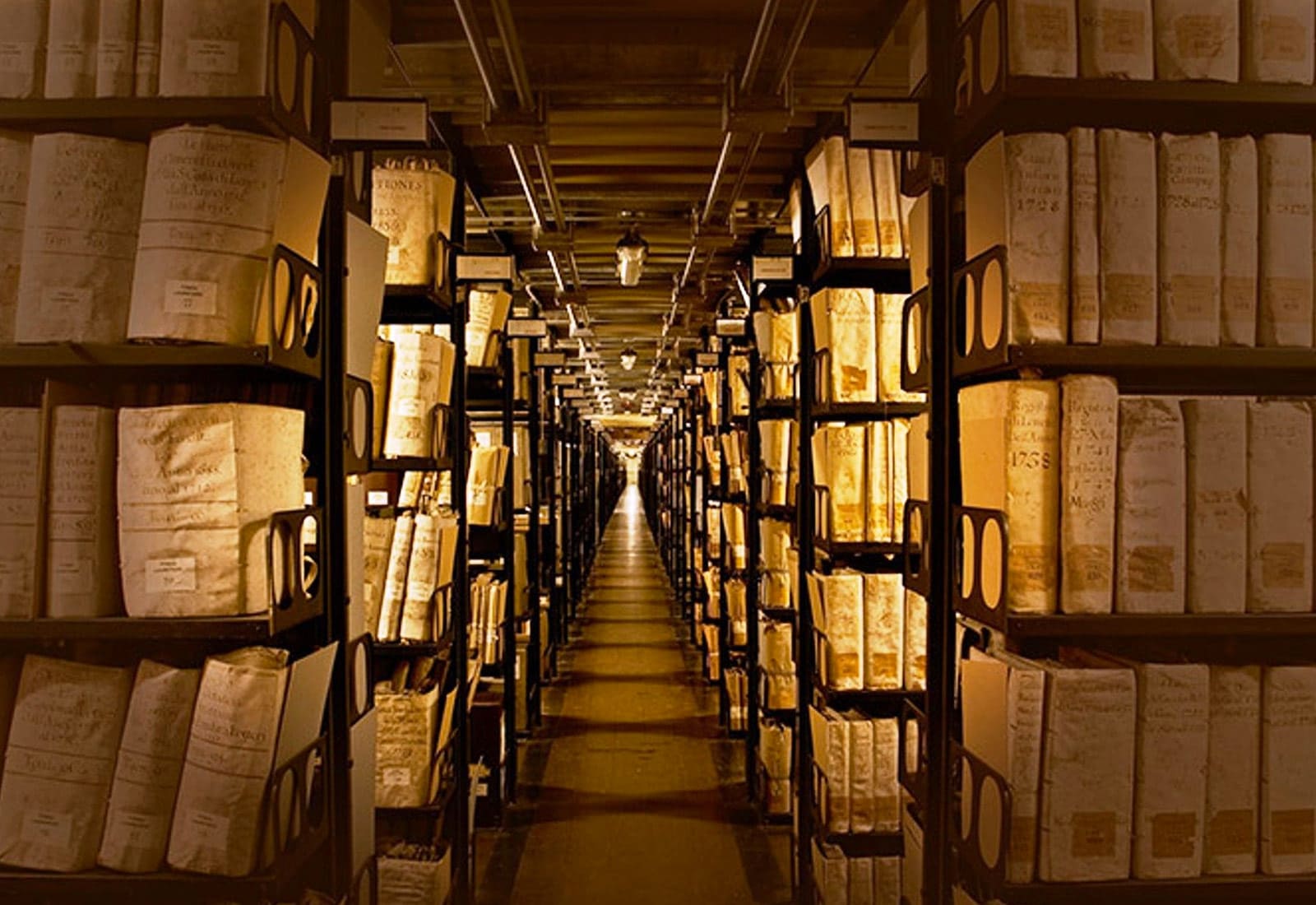

The underground repository of the Bourbaki Secret Archives is a storage facility built beneath the cave of the former Capoulade Cafe. Given its sporadic use by staff and scholars, the entire space – including the Gallery of all intermediate versions of every damned Bourbaki book, the section reserved to Bourbaki’s internal notes, such as his Diktats, and all numbers of La Tribu, and the Miscellania, containing personal notes and other prullaria once belonging to its members – is illuminated by amber lighting activated only when movement is detected by strategically placed sensors, and is guarded by a private security firm, hired by the ACNB.

This description (based on that of the Vatican Secret Archives in the book The Magdalene Reliquary by Gary McAvoy) is far from the actual situation. The Bourbaki Archive has been pieced together from legates donated by some of its former members (including Delsarte, Weil, de Possel, Cartan, Samuel, and others), and consist of well over a hundredth labeled carton and plastic cases, fitting easily in a few standard white Billy Ikea bookcases.

The publicly available Bourbaki Archive is even much smaller. The Association des collaborateurs de Nicolas Bourbaki has strong opinions on which items can be put online. For years the available issues of La Tribu were restricted to those before 1953. I was once told that one of the second generation Bourbaki-members vetoed further releases.

As a result, we only had the fading (and often coloured) memories of Bourbaki-members to rely on if we wanted to reconstruct key events, for example, Bourbaki’s reluctance to include category theory in its works. Rather than to work on source material, we had to content ourselves with interviews, such as this one, the relevant part starts at 51.40 into the clip. See here for some other interesting time-slots.

On a recent visit to the Bourbaki Archives I was happy to see that all volumes of “La Tribu” (the internal newsletter of Bourbaki) are now online from 1940 until 1960.

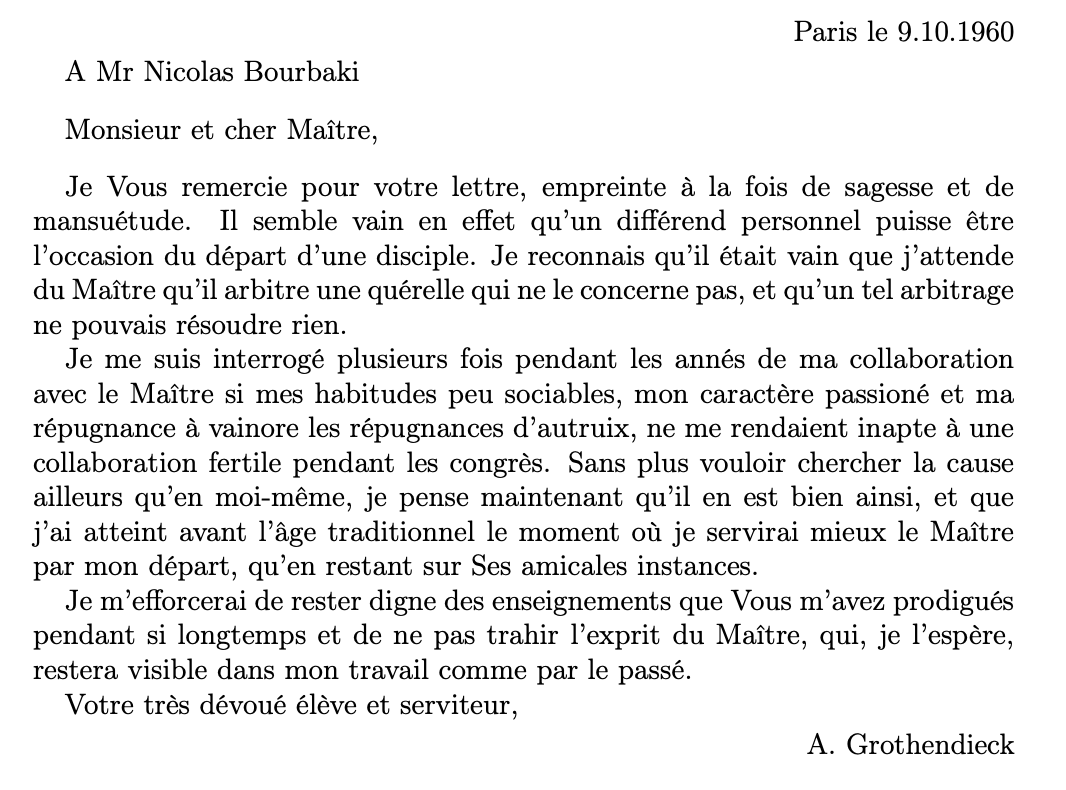

Okay, it’s not the entire story yet but, for all you Grothendieck aficionados out there, it should be enough as G resigned from Bourbaki in 1960 with this letter (see here for a translation).

Grothendieck was present at just twelve Bourbaki congresses in the period between 1955 and 1960 (he was also present as a ‘cobaye’ at a 1951 congress in Nancy).

The period 1955-60 was crucial in the modern development of algebraic geometry. Serre’s ‘FAC’ was published, as was Grothendieck’s ‘Tohoku-paper’, there was the influential Chevalley seminar, and the internal Bourbaki-fight about categories and the functorial view.

Perhaps the definite paper on the later issue is Ralf Kromer’s La ‘Machine de Grothendieck’ se fonde-t-elle seulement sur les vocables metamathematiques? Bourbaki et les categories au cours des annees cinquante.

Kromer had access to most issues of La Tribu until 1962 (from the Delsarte archive in Nancy), but still felt the need to justify his use of these sources to the ACNB (footnote 9 of his paper):

“L’autorisation que j’ai obtenue par le Comité scientifique des Archives de la création des mathématiques, unité du CNRS qui fut chargée jusqu’en 2003 de la mise à disposition de ces archives, me donne également le droit d’utiliser les sources datant des années postérieures à l’année 1953, que j’avais consultées auparavant aux Archives Jean Delsarte, soit avant que l’ACNB (Association des Collaborateurs de Nicolas Bourbaki) ne rende publique sa décision d’ouvrir ses archives et ne décide des parties qui seraient consultables.

J’ai ainsi bénéficié d’une occasion qui ne se présenterait sans doute plus aujourd’hui, mais c’est en toute légitimité que je puis m’appuyer sur cette riche documentation. Toutefois, la collection des Archives Jean Delsarte étant à son tour limitée aux années antérieures à 1963, je n’ai pu étudier la discussion ultérieure.”

The Association des Collaborateurs de Nicolas Bourbaki made retirement from active B-membership mandatory at the age of 50. One might expect of it to open up all documents in its archives which are older than fifty years.

Meanwhile, we’ll have a go at the 1940-1960 issues of La Tribu.

Leave a Comment