For three summers in a row, Bourbaki held its congres in ‘Sallieres-les-bains’, located near Die, in the Drôme.

- La Tribu 36, from June 27th till July 9th 1955

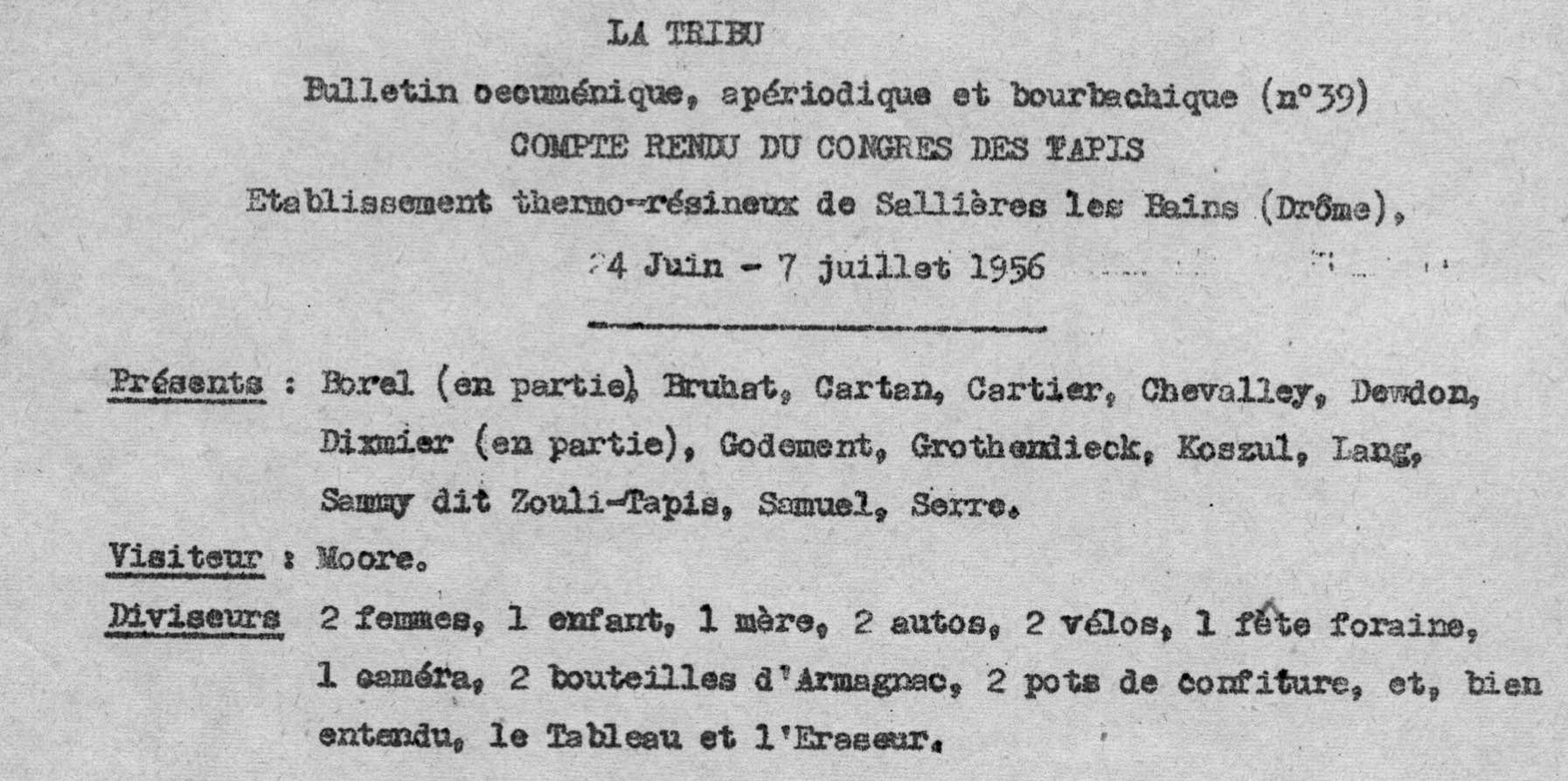

- La Tribu 39, from June 24th till July 7th 1956, ‘Congres des Tapis’

- La Tribu 42, from June 23rd till July 7th 1957, ‘Congres oecumenique du diabolo’

There are several ways to determine the exact location of a Bourbaki congres.

The quickest one is to get hold of the corresponding Diktat which often not only gives the address, but also travel instructions on how to get there. But strangely, no Diktats for congresses after 1953 are cleared by the ACNB.

Next, one can look in the previous La Tribu issue, as it contains a section on the next congres. In La Tribu 35 we find on page 2 : “Next congres : from June 25th till July 6th, in a location to be determined”. La Tribu 38 on page 5 reads (rough translation)

Next congres : will be held around the usual dates (June 23rd till July 7th, with a margin of 2 or 3 days). To facilitate things for Borel and Weil, Koko (=Koszul) will quickly look for a pleasant place in the Vosges or l’Alsace region. If this fails, he’ll immediately warn Cartan who will then take care of Die.

La Tribu 41 mentions on page 6: next congress will be held in Die from June 23rd till July 7th.

Finally, it may be that La Tribu itself gives more details. Strangely, La Tribu 36 is not among the issues recently cleared by the ACNB.

We know of its existence from Kromer’s paper La Machine de Grothendieck, and from a letter from Serre to Grothendieck from July 13th 1955 in which he writes that the Bourbaki congres in Sallieres-les-bains went well and that Grothendieck’s paper on Homological algebra (now known as the Tohoku-paper) was carefully read and converted everyone (‘even Dieudonne, who seems completely functorised’).

In La Tribu 39 we immediately strike gold, the heading tells us that the congres was held in the ‘Etablissement Thermo-resineux de Sallieres les bains’.

But, if you google for this, all you get are some pretty old postcards, such as this one

with one exception, a site set up to save the chapel of the Thermes de Sallieres-les-bains, which gives some historical information (google-translated):

“In Die, in the middle of the 19th century, the thermo-resinous establishments of Salières-les-bains opened. Until 1972, i.e. for 120 years, spa guests came there every summer to treat their bronchial tubes and rheumatism with the vapours of mugho pine. The center of Die and its cathedral being 4km away, it is in this 51m² chapel that the curists gathered. Mass was even sometimes said there because a priest was regularly among the spa guests. But after the closure, the small family farm can no longer maintain all the large buildings of the inn and their chapel, whose roof has now collapsed…”

And, there is the book Des bains de vapeurs térébenthinés aux pastilles de Pin mugho by Cécile Raynal, containing a short paragraph on the installation in Sallieres: (G-translate)

“Located a short distance from Martouret, this hydro-mineral establishment was created by a breeder, owner of the Sallieres estate, Mr. Taillotte. He equipped himself with facilities for resinous baths and also used hydrotherapy. More especially frequented by the patients of the surroundings, under the supervision of Dr. Magnan, a doctor from Die, the establishment charged moderate prices and functioned only in the summer. The installations would have lasted until the 1970s.”

So, it is perfectly possible that the Bourbakis stayed here in the mid 50ties. But, how did they know of this place and what’s the link with Cartan?

If you look at the map (Sallieres is the red marker) you’ll find in the immediate neighborhood the former Abbey of Valcroissant (for the Dome du Glandasse read La Tribu 42, page2)

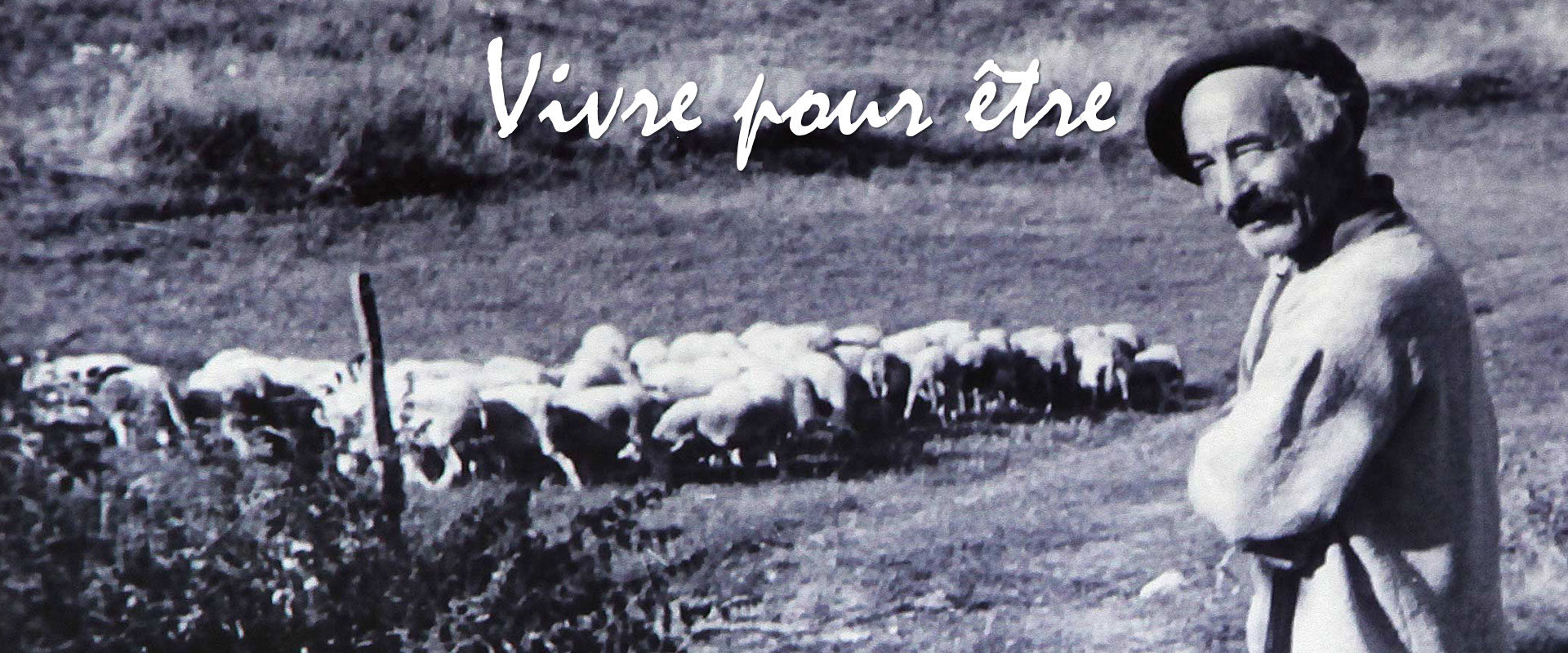

“The abbey was bought in the 1950s by the mathematician and philosopher Marcel Légaut and his wife, who chose to restore it while maintaining agricultural activity, particularly livestock. The restoration led in particular to the classification of the abbey in the inventory of historical monuments, a classification which took place on October 25, 1971. The restoration continued in the 21st century, led by Rémy Légaut, son of Marcel, his wife Martine, and the association of “Friends of Valcroissant” created by André Pitte and Serge Durand.”

Marcel Legaut was a very interesting person, who did a Grothendieck avant-la-lettre. From wikipedia

“Marcel Légaut was born in Paris, where he received his Ph.D. in Mathematics from the École Normale Supérieure in 1925. He taught in various faculties (among them Rennes and Lyon) until 1943. Under the impact of the Second World War and the rapid French defeat in 1940, Légaut acknowledged the lack of certain fundamental aspects in his life as well as in the lives of other university professors and civil servants. That is why he tried to alternate teaching with farm work. After three years his project was no longer accepted and he left the University to live as a shepherd in the Pré-Alpes (Haut-Diois).”

Legaut also wrote about twenty books on catholic faith. Again from wikipedia (and compare to Grothendieck’s later years):

“Légaut offers, in his books, his meditation, his testimony and his prayer, resulting from the intimate conversation he holds with himself, with his friends and with God. Meditation, testimony and prayer are, in every human being, the three categories corresponding to the different destinataries of intimate “conversation”, which is, in short, the sort of communication that every spiritual life aims to achieve according to its deep instinct.”

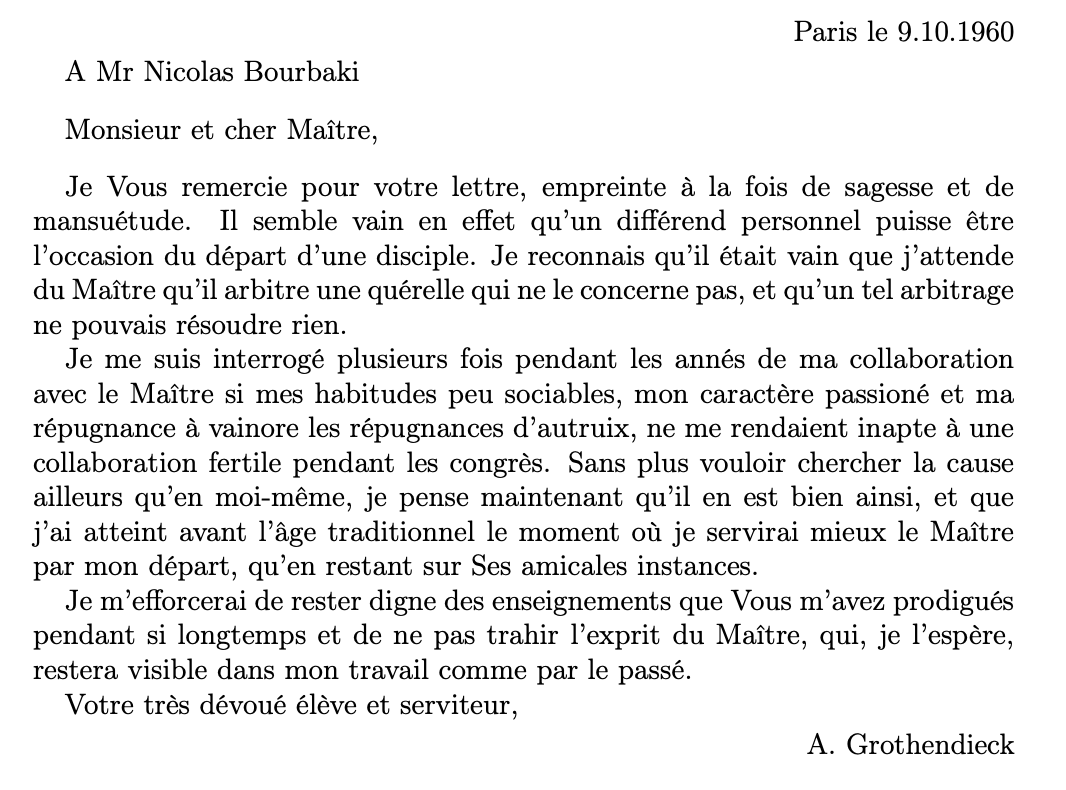

Marcel Legaut is also one of the 24 ‘mutants’ in Grothendieck’s Clef des songes. Is it possible the two met during the Bourbaki congres in Sallieres-les-bains?

In this article on Legaut there’s this recollection by Pierre Cartier:

“Pierre Cartier believes that Grothendieck and Légaut had already met in the fifties, on the occasion of a Bourbaki meeting which took place in the Alps in Pelvoux-le Poët. Légaut, who lived at no great distance, was acquainted with Henri Cartan, André Weil and other members of Bourbaki. Cartier remembers that he himself visited Légaut at the time, and recalls Légaut actually attending the Bourbaki meeting.”

I beg to differ on the place of the Bourbaki meeting, I’m convinced it was during a congres in Sallieres-les-bains. We now also see the link with Cartan. Probably it was Legaut who mentioned the nearby wellness-center to Cartan.

Do the buildings of the ‘Etablissement Thermo-resineux de Sallieres les bains’ still exist, and what is their exact location?

If you intend to go on a little pelgrimage, point your GPS to 44.737347, 5.398835. Perhaps you can stay for a few days in the renovated Abbaye de Valcroissant, they offer courses in herbal medicine, aromatherapy and natural cosmetics, which are organised from March to November.

Leave a Comment