Just as cartographers like

Just as cartographers like

Mercator drew maps of

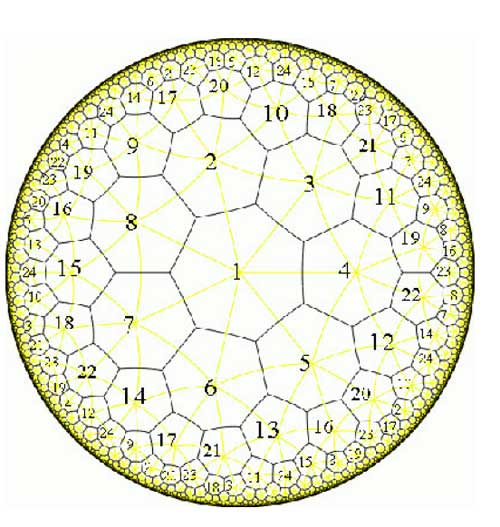

the then known world, we draw dessins

d ‘enfants to depict the

associated algebraic curve defined over

$\overline{\mathbb{Q}} $.

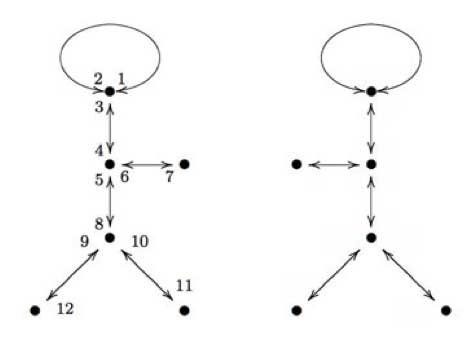

In order to see that such a dessin

d’enfant determines a permutation representation of one of

Grothendieck’s cartographic groups, $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}),

\Gamma_0(2) $ or $\Gamma(2) $ we need to have realizations of these

groups (as well as their close relatives

$PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}),GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ and $PGL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $) in

terms of generators and relations.

As this lesson will be rather

technical I’d better first explain what we will prove (so that you can

skip it if you feel comfortable with the statements) and why we want to

prove it. What we will prove in detail below is that these groups

can be written as free (or amalgamated) group products. We will explain

what this means and will establish that

$PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) = C_2

\ast C_3, \Gamma_0(2) = C_2 \ast C_{\infty}, \Gamma(2)

= C_{\infty} \ast C_{\infty} $

$SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) =

C_4 \ast_{C_2} C_6, GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) = D_4 \ast_{D_2} D_6,

PGL_2(\mathbb{Z}) = D_2 \ast_{C_2} D_3 $

where $C_n $ resp.

$D_n $ are the cyclic (resp. dihedral) groups. The importance of these

facts it that they will allow us to view the set of (isomorphism classes

of) finite dimensional representations of these groups as

noncommutative manifolds . Looking at the statements above we

see that these arithmetical groups can be build up from the first

examples in any course on finite groups : cyclic and dihedral

groups.

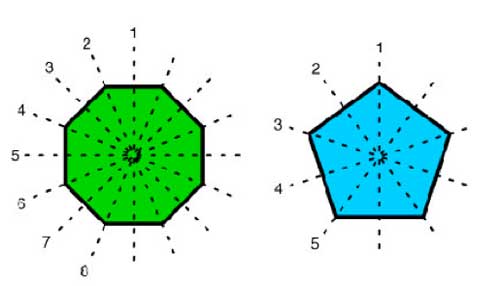

Recall that the cyclic group of order n, $C_n $ is the group of

rotations of a regular n-gon (so is generated by a rotation r with

angle $\frac{2 \pi}{n} $ and has defining relation $r^n = 1 $, where 1

is the identity). However, regular n-gons have more symmetries :

flipping over one of its n lines of symmetry

The dihedral group $D_n $ is the group generated by the n

rotations and by these n flips. If, as before r is a generating

rotation and d is one of the flips, then it is easy to see that the

dihedral group is generated by r and d and satisfied the defining

relations

$r^n=1 $ and $d^2 = 1 = (rd)^2 $

Flipping twice

does nothing and to see the relation $~(rd)^2=1 $ check that doing twice a

rotation followed by a flip brings all vertices back to their original

location. The dihedral group $D_n $ has 2n elements, the n-rotations

$r^i $ and the n flips $dr^i $.

In fact, to get at the cartographic

groups we will only need the groups $D_4, D_6 $ and their

subgroups. Let us start by finding generators of the largest

group $GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ which is the group of all invertible $2

\times 2 $ matrices with integer coefficients.

Consider the

elements

$U = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix},

V = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ -1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}/tex] and $R =

\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $

and form the

matrices

$X = UV = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 \\ 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}, Y = VU = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1

\end{bmatrix} $

By induction we prove the following relations in

$GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $

$X^n \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d

\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} a-nc & b-nd \\ c & d \end{bmatrix} $

and $\begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c& d \end{bmatrix} X^n =

\begin{bmatrix} a & b-na \\ c & d-nc \end{bmatrix} $

$Y^n \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix} =

\begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c+na & d+nb \end{bmatrix} $ and

$\begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix} Y^n = \begin{bmatrix}

a+nb & b \\ c+nd & d \end{bmatrix} $

The determinant ad-bc of

a matrix in $GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ must be $\pm 1 $ whence all rows and

columns of

$\begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix} \in

GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $

consist of coprime numbers and hence a and

c can be reduced modulo each other by left multiplication by a power

of X or Y until one of them is zero and the other is $\pm 1 $. We

may even assume that $a = \pm 1 $ (if not, left multiply with U).

So,

by left multiplication by powers of X and Y and U we can bring any

element of $GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ into the form

$\begin{bmatrix}

\pm 1 & \beta \\ 0 & \pm 1 \end{bmatrix} $

and again by left

multiplication by a power of X we can bring it in one of the four

forms

$\begin{bmatrix} \pm 1 & 0 \\ 0 & \pm 1 \end{bmatrix}

= { 1,UR,RU,U^2 } $

This proves that $GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ is

generated by the elements U,V and R.

Similarly, the group

$SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ of all $2 \times 2 $ integer matrices with

determinant 1 is generated by the elements U and V as using the

above method and the restriction on the determinant we will end up with

one of the two matrices

${ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix} } =

{ 1,U^2 } $

so we never need the matrix R. As for

relations, there are some obvious relations among the matrices U,V and

R, namely

$U^2=V^3 $ and $1=U^4=R^2=(RU)^2=(RV)^2$ $

The

real problem is to prove that all remaining relations are consequences

of these basic ones. As R clearly has order two and its commutation

relations with U and V are just $RU=U^{-1}R $ and $RV=V^{-1}R $ we can

pull R in any relation to the far right and (possibly after

multiplying on the right with R) are left to prove that the only

relations among U and V are consequences of $U^2=V^3 $ and

$U^4=1=V^6 $.

Because $U^2=V^3 $ this element is central in the

group generated by U and V (which we have seen to be

$SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $) and if we quotient it out we get the modular

group

$\Gamma = PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $

Hence in order to prove our claim

it suffices that

$PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) = \langle

\overline{U},\overline{V} : \overline{U}^2=\overline{V}^3=1

\rangle $

Phrased differently, we have to show that

$PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ is the free group product of the cyclic groups of

order two and three (those generated by $u = \overline{U} $ and

$v=\overline{V} $) $C_2 \ast C_3 $

Any element of this free group

product is of the form $~(u)v^{a_1}uv^{a_2}u \ldots

uv^{a_k}(u) $ where beginning and trailing u are optional and

all $a_i $ are either 1 or 2.

So we have to show that in

$PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ no such word can give the identity

element. Today, we will first sketch the classical argument based

on the theory of groups acting on trees due to Jean-Pierre

Serre and Hyman Bass. Tomorrow, we will give a short elegant proof due to

Roger Alperin and draw

consequences to the description of the carthographic groups as

amalgamated free products of cyclic and dihedral groups.

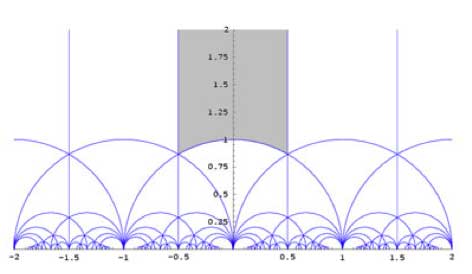

Recall

that $GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ acts via Moebius

transformations on

the complex plane $\mathbb{C} = \mathbb{R}^2 $ (actually it is an

action on the Riemann sphere $\mathbb{P}^1_{\mathbb{C}} $) given by the

maps

$\begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix}.z =

\frac{az+b}{cz+d} $

Note that the action of the

center of $GL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ (that is of $\pm \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0

\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $) acts trivially, so it is really an action of

$PGL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $.

As R interchanges the upper and lower half-plane

we might as well restrict to the action of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ on the

upper-halfplane $\mathcal{H} $. It is quite easy to see that a

fundamental domain

for this action is given by the greyed-out area

To see that any $z \in \mathcal{H} $ can be taken into this

region by an element of $PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ note the following two

Moebius transformations

$\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}.z = z+1 $ and $\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ -1

& 0 \end{bmatrix}.z = -\frac{1}{z} $

The first

operation takes any z into a strip of length one, for example that

with Re(z) between $-\frac{1}{2} $ and $\frac{1}{2} $ and the second

interchanges points within and outside the unit-circle, so combining the

two we get any z into the greyed-out region. Actually, we could have

taken any of the regions in the above tiling as our fundamental domain

as they are all translates of the greyed-out region by an element of

$PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $.

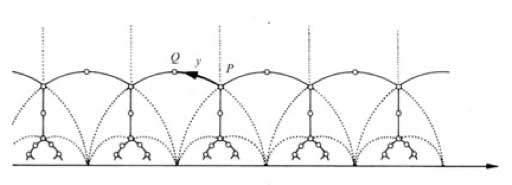

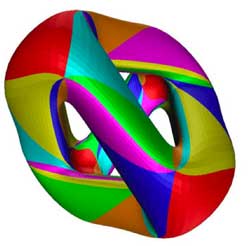

Of course, points on the boundary of the

greyed-out fundamental region need to be identified (in order to get the

identification of $\overline{\mathcal{H}/PSL_2(\mathbb{Z})} $ with the

Riemann sphere $S^2=\mathbb{P}^1_{\mathbb{C}} $). For example, the two

halves of the boundary by the unit circle are interchanged by the action

of the map $z \rightarrow -\frac{1}{z} $ and if we take the translates under

$PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) $ of the indicated circle-part

we get a connected tree with fundamental domain the circle

part bounded by i and $\rho = \frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i $.

Calculating the stabilizer subgroup of i (that is, the subgroup of

elements fixing i) we get that this subgroup

is $\langle u \rangle = C_2 $ whereas the stabilizer subgroup of

$\rho $ is $\langle v \rangle = C_3 $.

Using this facts and the general

results of Jean-Pierre Serres book Trees

one deduces that $PSL_2(\mathbb{Z}) = C_2 \ast C_3 $

and hence that the obvious relations among U,V and R given above do

indeed generate all relations.

As a tribute for this clever

As a tribute for this clever