Wikipedia claims:

“The word scheme was first used in the 1956 Chevalley Seminar, in which Chevalley was pursuing Zariski’s ideas.”

and refers to the lecture by Chevalley ‘Les schemas’, given on December 12th, 1955 at the ENS-based ‘Seminaire Henri Cartan’ (in fact, that year it was called the Cartan-Chevalley seminar, and the next year Chevalley set up his own seminar at the ENS).

Items recently added to the online Bourbaki Archive give us new information on time and place of the birth of the concept of schemes.

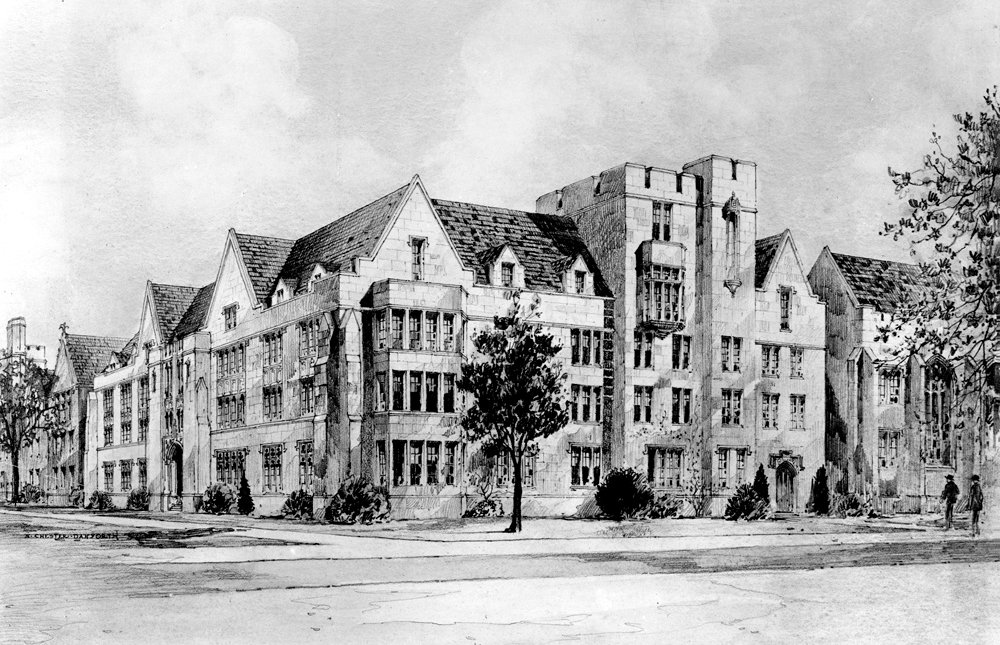

From May 30th till June 2nd 1955 the ‘second caucus des Illinois’ Bourbaki-congress was held in ‘le grand salon d’Eckhart Hall’ at the University of Chicago (Weil’s place at that time).

Only six of the Bourbaki members were present:

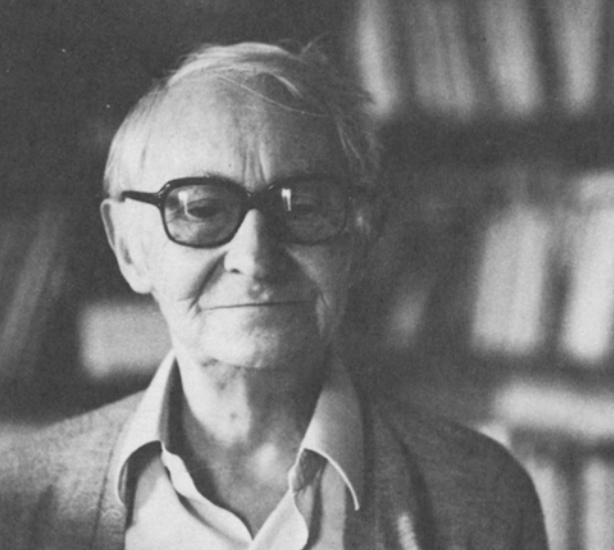

- Jean Dieudonne (then 49), the scribe of the Bourbaki-gang.

- Andre Weil (then 49), called ‘Le Pape de Chicago’ in La Tribu, and responsible for his ‘Foundations of Algebraic Geometry’.

- Claude Chevalley (then 46), who wanted a better, more workable version of algebraic geometry. He was just nominated professor at the Sorbonne, and was prepping for his seminar on algebraic geometry (with Cartan) in the fall.

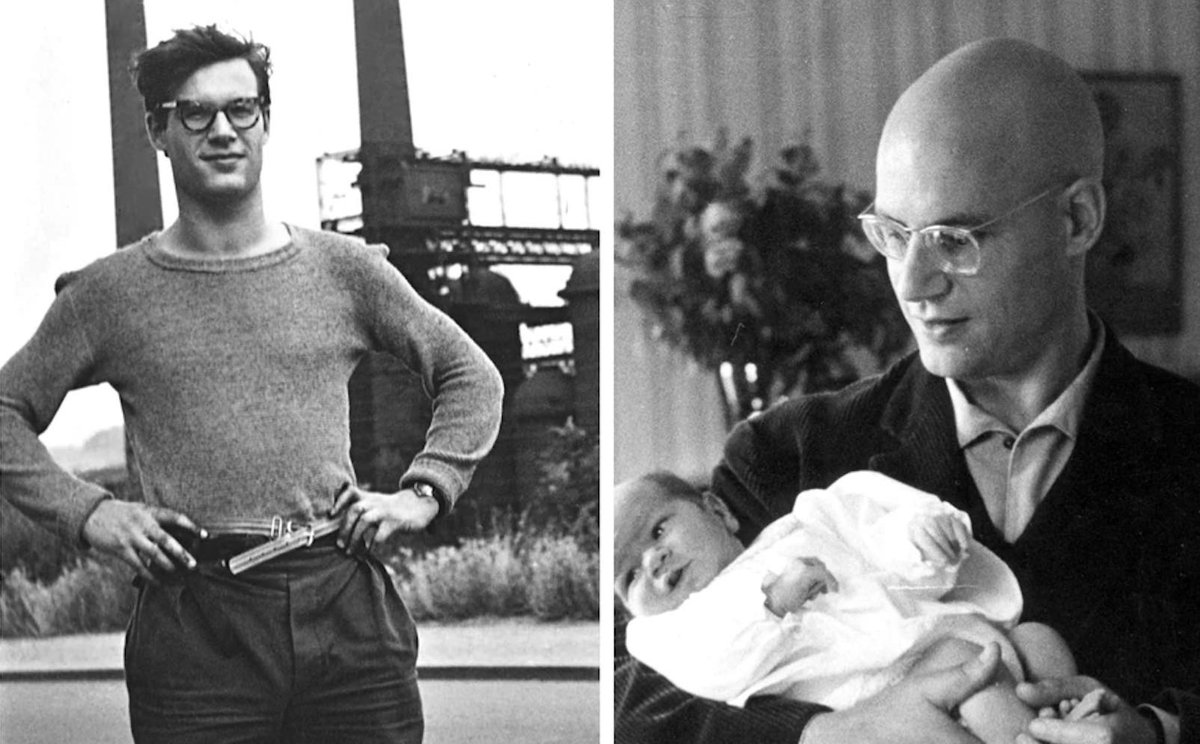

- Pierre Samuel (then 34), who studied in France but got his Ph.D. in 1949 from Princeton under the supervision of Oscar Zariski. He was a Bourbaki-guinea pig in 1945, and from 1947 attended most Bourbaki congresses. He just got his book Methodes d’algebre abstraite en geometrie algebrique published.

- Armand Borel (then 32), a Swiss mathematician who was in Paris from 1949 and obtained his Ph.D. under Jean Leray before moving on to the IAS in 1957. He was present at 9 of the Bourbaki congresses between 1955 and 1960.

- Serge Lang (then 28), a French-American mathematician who got his Ph.D. in 1951 from Princeton under Emil Artin. In 1955, he just got a position at the University of Chicago, which he held until 1971. He attended 7 Bourbaki congresses between 1955 and 1960.

The issue of La Tribu of the Eckhart-Hall congress is entirely devoted to algebraic geometry, and starts off with a bang:

“The Caucus did not judge the plan of La Ciotat above all reproaches, and proposed a completely different plan.

I – Schemes

II – Theory of multiplicities for schemes

III – Varieties

IV – Calculation of cycles

V – Divisors

VI – Projective geometry

etc.”

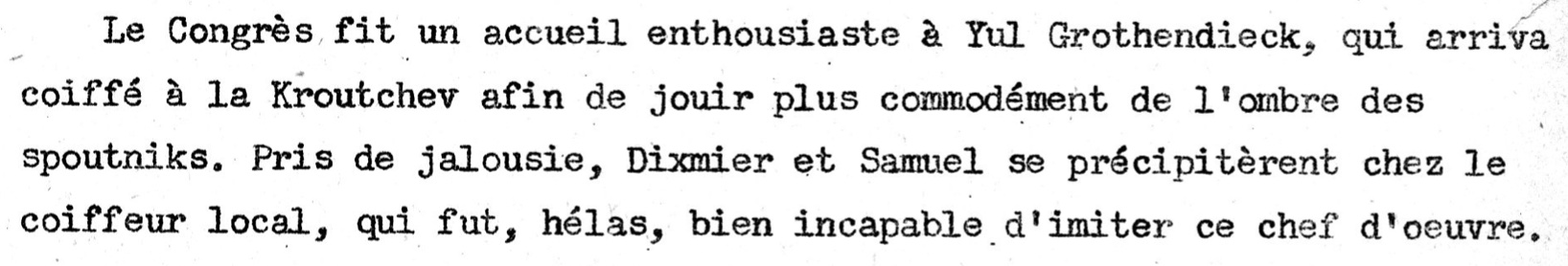

In the spring of that year (February 27th – March 6th, 1955) a Bourbaki congress was held ‘Chez Patrice’ at La Ciotat, hosting a different group of Bourbaki members (Samuel was the singleton intersection) : Henri Cartan (then 51), Jacques Dixmier (then 31), Jean-Louis Koszul (then 34), and Jean-Pierre Serre (then 29, and fresh Fields medaillist).

In the La Ciotat-Tribu,nr. 35 there are also a great number of pages (page 14 – 25) used to explain a general plan to deal with algebraic geometry. Their summary (page 3-4):

“Algebraic Geometry : She has a very nice face.

Chap I : Algebraic varieties

Chap II : The rest of Chap. I

Chap III : Divisors

Chap IV : Intersections”

There’s much more to say comparing these two plans, but that’ll be for another day.

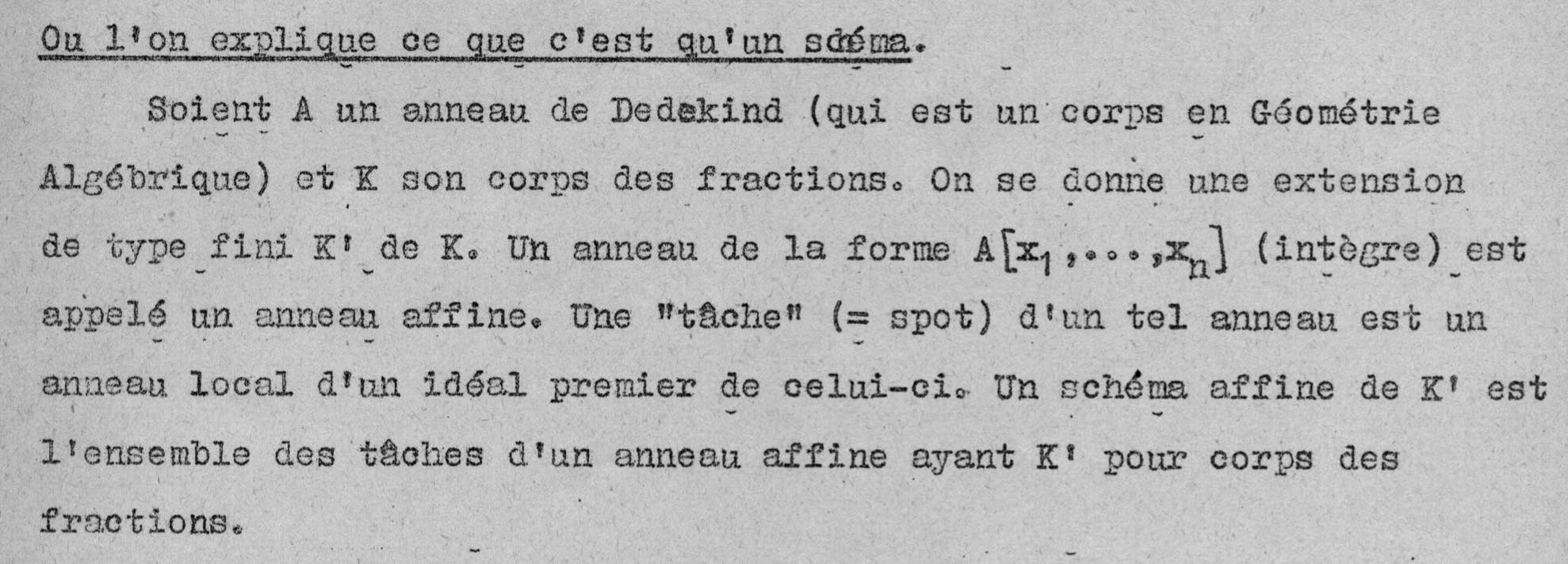

We’ve just read the word ‘schemes’ for the first (?) time. That unnumbered La Tribu continues on page 3 with “where one explains what a scheme is”:

So, what was their first idea of a scheme?

Well, you had your favourite Dedekind domain $D$, and you considered all rings of finite type over $D$. Sorry, not all rings, just all domains because such a ring $R$ had to have a field of fractions $K$ which was of finite type over $k$ the field of fractions of your Dedekind domain $D$.

They say that Dedekind domains are the algebraic geometrical equivalent of fields. Yeah well, as they only consider $D$-rings the geometric object associated to $D$ is the terminal object, much like a point if $D$ is an algebraically closed field.

But then, what is this geometric object associated to a domain $R$?

In this stage, still under the influence of Weil’s focus on valuations and their specialisations, they (Chevalley?) take as the geometric object $\mathbf{Spec}(R)$, the set of all ‘spots’ (taches), that is, local rings in $K$ which are the localisations of $R$ at prime ideals. So, instead of taking the set of all prime ideals, they prefer to take the set of all stalks of the (coming) structure sheaf.

But then, speaking about sheaves is rather futile as there is no trace of any topology on this set, then. Also, they make a big fuss about not wanting to define a general schema by gluing together these ‘affine’ schemes, but then they introduce a notion of ‘apparentement’ of spots which basically means the same thing.

It is still very early days, and there’s a lot more to say on this, but if no further documents come to light, I’d say that the birthplace of ‘schemes’, that is , the place where the first time there was a documented consensus on the notion, is Eckhart Hall in Chicago.

Leave a Comment