Arnold has written a follow-up to the paper mentioned last time called “Polymathematics : is mathematics a single science or a set of arts?” (or here for a (huge) PDF-conversion).

On page 8 of that paper is a nice summary of his 25 trinities :

I learned of this newer paper from a comment by Frederic Chapoton who maintains a nice webpage dedicated to trinities.

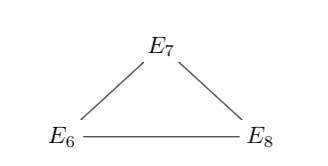

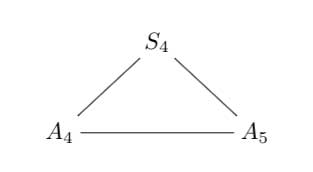

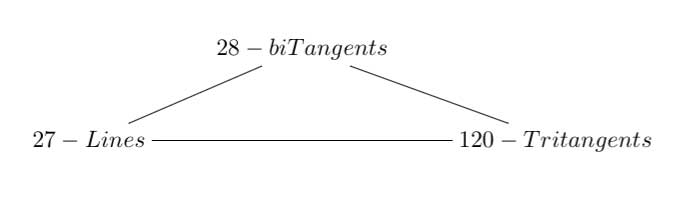

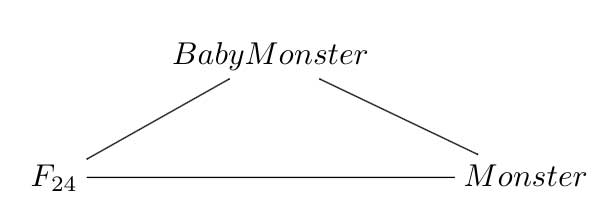

In his list there is one trinity on sporadic groups :

where $F_{24} $ is the Fischer simple group of order $2^{21}.3^{16}.5^2.7^3.11.13.17.23.29 = 1255205709190661721292800 $, which is the third largest sporadic group (the two larger ones being the Baby Monster and the Monster itself).

I don’t know what the rationale is behind this trinity. But I’d like to recall the (Baby)Monster history as a warning against the trinity-reflex. Sometimes, there is just no way to extend a would be trinity.

The story comes from Mark Ronan’s book Symmetry and the Monster on page 178.

Let’s remind ourselves how we got here. A few years earlier, Fischer has created his ‘transposition’ groups Fi22, Fi23, and Fi24. He had called them M(22), M(23), and M(24), because they were related to Mathieu’s groups M22,M23, and M24, and since he used Fi22 to create his new group of mirror symmetries, he tentatively called it $M^{22} $.

It seemed to appear as a cross-section in something even bigger, and as this larger group was clearly associated with Fi24, he labeled it $M^{24} $. Was there something in between that could be called $M^{23} $?

Fischer visited Cambridge to talk on his new work, and Conway named these three potential groups the Baby Monster, the Middle Monster, and the Super Monster. When it became clear that the Middle Monster didn’t exist, Conway settled on the names Baby Monster and Monster, and this became the standard terminology.

Marcus du Sautoy’s account in Finding Moonshine is slightly different. He tells on page 322 that the Super Monster didn’t exist. Anyone knowing the factual story?

Some mathematical trickery later revealed that the Super Monster was going to be impossible to build: there were certain features that contradicted each other. It was just a mirage, which vanished under closer scrutiny. But the other two were still looking robust. The Middle Monster was rechristened simply the Monster.

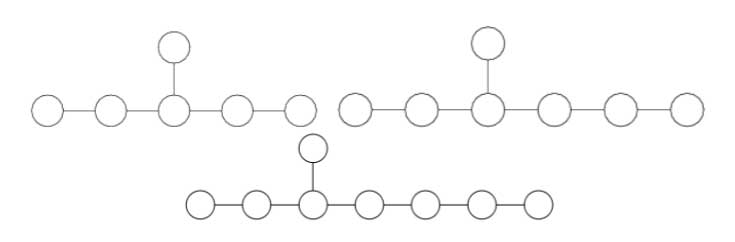

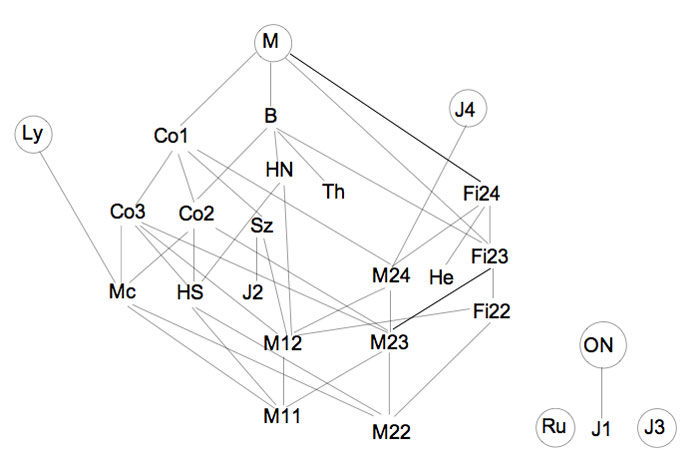

And, the inclusion diagram of the sporadic simples tells yet another story.

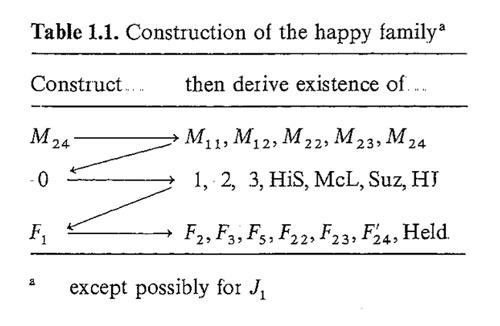

Anyhow, this inclusion diagram is helpful in seeing the three generations of the Happy Family (as well as the Pariahs) of the sporadic groups, terminology invented by Robert Griess in his 100+p Inventiones paper on the construction of the Monster (which he liked to call, for obvious reasons, the Friendly Giant denoted by FG).

The happy family appears in Table 1.1. of the introduction.

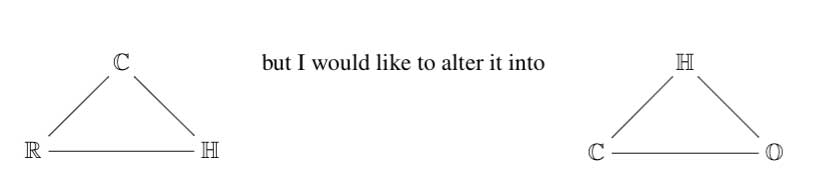

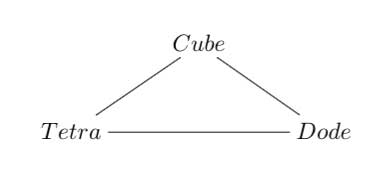

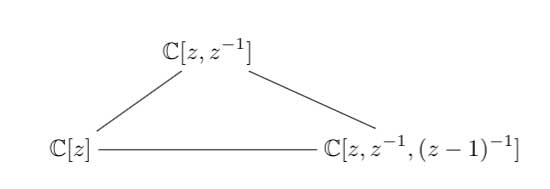

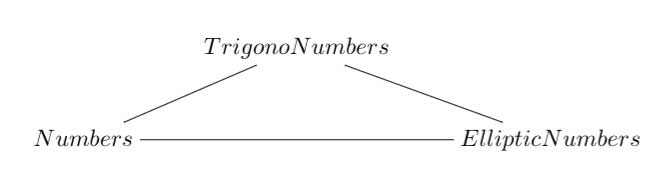

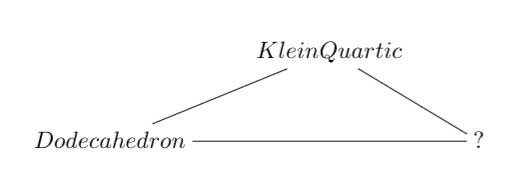

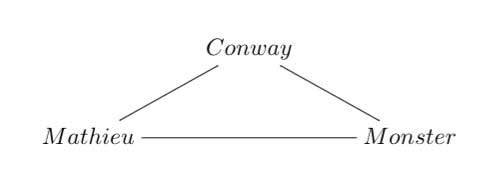

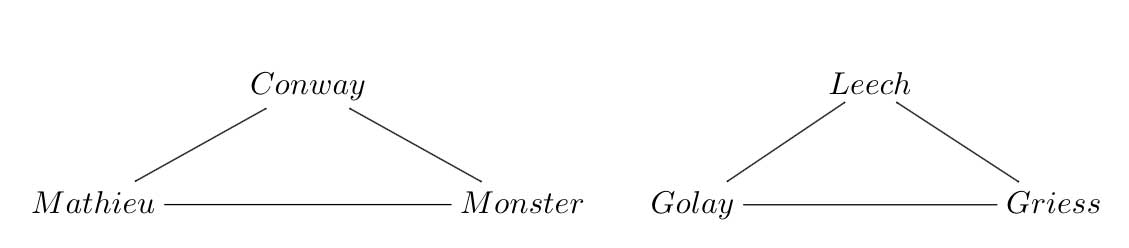

It was this picture that made me propose the trinity on the left below in the previous post. I now like to add another trinity on the right, and, the connection between the two is clear.

Here $Golay $ denotes the extended binary Golay code of which the Mathieu group $M_{24} $ is the automorphism group. $Leech $ is of course the 24-dimensional Leech lattice of which the automorphism group is a double cover of the Conway group $Co_1 $. $Griess $ is the Griess algebra which is a nonassociative 196884-dimensional algebra of which the automorphism group is the Monster.

I am aware of a construction of the Leech lattice involving the quaternions (the icosian construction of chapter 8, section 2.2 of SPLAG). Does anyone know of a construction of the Griess algebra involving octonions???

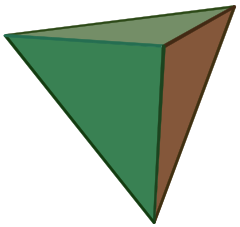

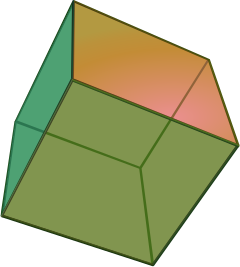

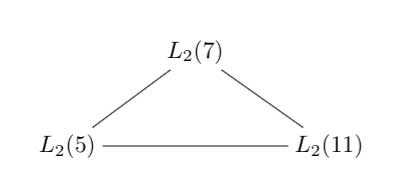

3 Comments Referring to the triple of exceptional Galois groups $L_2(5),L_2(7),L_2(11) $ and its connection to the Platonic solids I

Referring to the triple of exceptional Galois groups $L_2(5),L_2(7),L_2(11) $ and its connection to the Platonic solids I