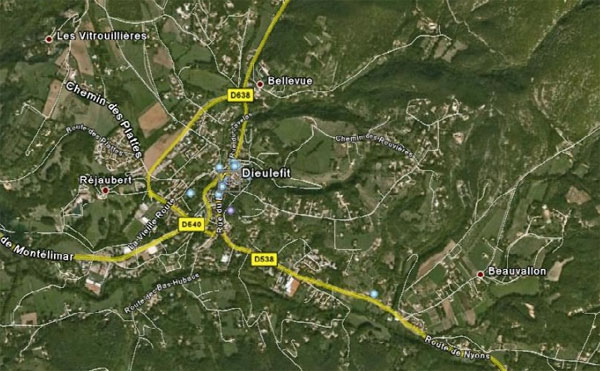

The last pre-war Bourbaki congress, held in september 1938 in Dieulefit, is surrounded by mystery. Compared to previous meetings, fewer documents are preserved in the Bourbaki archives and some sentences in the surviving notules have been made illegible. We will have to determine the exact location of the Dieulefit-meeting before we can understand why this had to be done. It’s Bourbaki’s own tiny contribution to ‘le miracle de silence’…

First, the few facts we know about this Bourbaki congress, mostly from Andre Weil‘s autobiography ‘The Apprenticeship of a Mathematician’.

First, the few facts we know about this Bourbaki congress, mostly from Andre Weil‘s autobiography ‘The Apprenticeship of a Mathematician’.

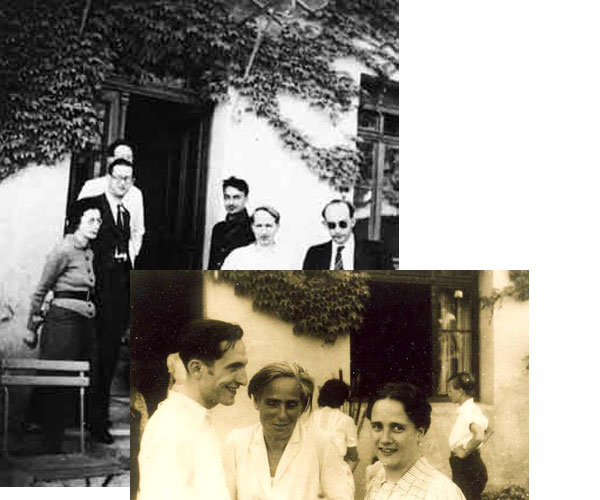

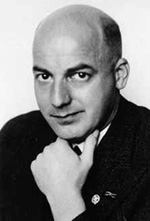

The meeting was held in Dieulefit in the Drome-Provencale region, sometime in september 1938 prior to the Munich Agreement (more on this next time). We know that Elie Cartan did accept Bourbaki’s invitation to join them and there is this one famous photograph of the meeting. From left to right : Simone Weil (accompanying Andre), Charles Pison, Andre Weil (hidden), Jean Dieudonne (sitting), Claude Chabauty, Charles Ehresmann, and Jean Delsarte.

Failing further written documentation, ‘all’ we have to do in order to pinpoint the exact location of the meeting is to find a match between this photograph and some building in Dieulefit…

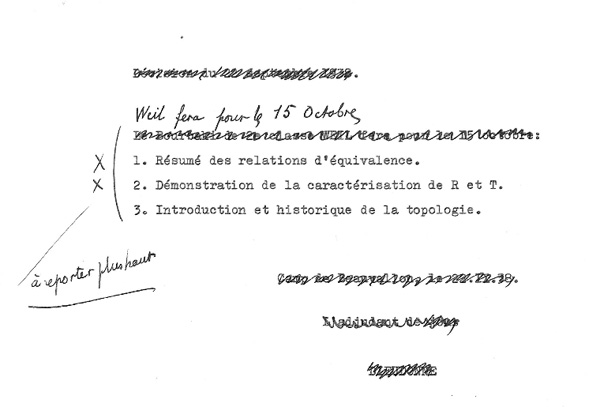

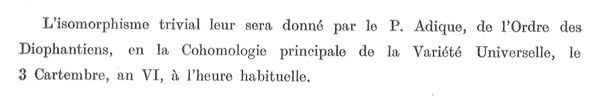

The crucial clue is provided by the couple of sentences, on the final page of the Bourbaki-archive document deldi_001 Engagements de Dieulefit, someone (Jean Delsarte?) has tried to make illegible (probably early on).

Blowing the picture up, it isn’t too hard to guess that the header should read ‘Décision du 22 septembre 1938’ and that the first sentence is ‘Le Bourbaki de 2e classe WEIL fera pour le 15 octobre’. The document is signed

Camp de Beauvallon, le 22.IX.38.

L’adjudant de jour

DIEUDONNE

Now we are getting somewhere. Beauvallon is the name of an hamlet of Dieulefit, situated approximately 2.5km to the east of the center.

Beauvallon is rather famous for its School, founded in 1929 by Marguerite Soubeyran and Catherine Krafft, which was the first ‘modern’ boarding school in France for both boys and girls having behavioral problems. From 1936 on the school’s director was Simone Monnier.

These three women were politically active and frequented several circles. Already in 1938 (at about the time of the Bourbaki congress) they knew the reality of the Nazi persecutions and planned to prepare their school to welcome, care for and protect refugees and Jewish children.

From 1936 on about 20 Spanish republican refugees found a home here and in the ‘pension’ next to the school. When the war started, about 1500 people were hidden from the German occupation in Dieulefit (having a total population of 3500) : Jewish children, intellectuals, artists, trade union leaders, etc. etc. many in the Ecole and the Pension.

Because of the towns solidarity with the refugees, none were betrayed to the Germans, Le miracle de silence à Dieulefit.

It earned the three Ecole-women the title of “Juste” after the war. More on this period can be read here.

But what does this have to do with Bourbaki? Well, we claim that the venue of the 1938 Bourbaki congress was the Ecole de Beauvallon and they probably used Le Pension for their lodgings.

We have photographic evidence comparing the Bourbaki picture with a picture taken in 1943 at the Ecole (the woman in the middle is Marguerite Soubeyran). Compare the distance between door and window, the division of the windows and the ivy on the wall.

Below two photographs of the entire school building : on the left, the school with ‘Le Pension’ next to it around 1938 (the ivy clad wall with the Bourbaki-door is to the right) and on the right, the present Ecole de Beauvallon (this site also contains a lot of historical material). The ivy has gone, but the main features of the building are still intact, only the shape of the small roof above the Bourbaki-door has changed.

During their stay, it is likely the Bourbakis became aware of the plans the school had would war break out. Probably, Jean Delsarte removed all explicit mention to the Ecole de Beauvallon from the archives upon their return. Bourbaki’s own small contribution to Dieulefit’s miracle of silence.

Leave a Comment

For example, the local-global, or

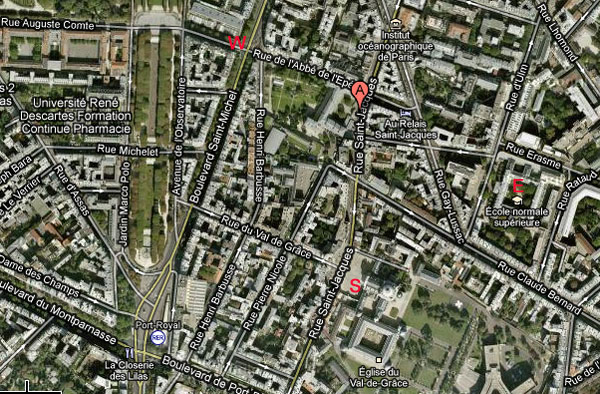

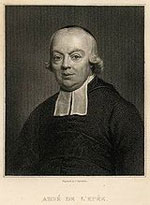

For example, the local-global, or  Crossing the boulevard Saint-Michel, one enters the 5-th arrondissement via the … rue de l’Abbe de l’Epee…

Crossing the boulevard Saint-Michel, one enters the 5-th arrondissement via the … rue de l’Abbe de l’Epee…