A few days before Halloween, Norbert Dufourcq (who died december 17th 1990…), sent me a comment, containing lots of useful information, hinting I did get it wrong about the church of the Bourbali wedding in the previous post.

Norbert Dufourcq, an organist and student of Andre Machall, the organist-in-charge at the Saint-Germain-des-Prés church in 1939, the place where I speculated the Bourbaki wedding took place, concluded his comment with :

“P.S. Lieven, you _do_ know about the Schola Cantorum, now, don’t you?!?”.

Euh… actually … no, I did not …

La Schola Cantorum is a private music school in Paris. It was founded in 1894 by Charles Bordes, Alexandre Guilmant and Vincent d’Indy as a counterbalance to the Paris Conservatoire’s emphasis on opera. Its alumni include many significant figures in 20th century music, such as Erik Satie and Cole Porter.

La Schola Cantorum is a private music school in Paris. It was founded in 1894 by Charles Bordes, Alexandre Guilmant and Vincent d’Indy as a counterbalance to the Paris Conservatoire’s emphasis on opera. Its alumni include many significant figures in 20th century music, such as Erik Satie and Cole Porter.

Schola Cantorum is situated 69, rue Saint Jacques, Paris, just around the corner of the Ecole Normal Superieure, home base to the Bourbakis. In fact, closer investigation reveals striking similarities and very close connections between the circle of artists at la Schola and the Bourbaki group.

In december 1934, the exact month the Bourbaki group was formed, a radical reorganisation took place at the Schola, when Nestor Lejeune became the new director. He invited several young musicians, many from the famous Dukas-class, to take up teaching positions at the Schola.

Here’s a picture of part of the Dukas class of 1929, several of its members will play a role in the upcoming events :

from left to right next to the piano : Pierre Maillard-Verger, Elsa Barraine, Yvonne Desportes, Tony Aubin, Pierre Revel, Georges Favre, Paul Dukas, René Duclos, Georges Hugon, Maurice Duruflé. Seated on the right : Claude Arrieu, Olivier Messiaen.

The mid-1930s in Paris saw the emergence of two closely-related groups with a membership which overlapped : La Spirale and La Jeune France. La Spirale was founded in 1935 under the leadership of Georges Migot; its other committee members were Paul Le Flem, his pupil André Jolivet, Edouard Sciortino, Claire Delbos, her husband Olivier Messiaen, Daniel-Lesur and Jules Le Febvre. The common link between almost all of these musicians was their connection with the Schola Cantorum.

On the left : Les Jeunes Musiciens Français : André Jolivet on the Piano. Standing from left to right :

On the left : Les Jeunes Musiciens Français : André Jolivet on the Piano. Standing from left to right :

Olivier Messiaen, Yves Baudrier, Daniel-Lesur.

Nigel Simeone wrote this about Messiaen and La Jeune France :

“The extremely original and independent-minded Messiaen had already shown himself to be a rather unexpected enthusiast for joining groups: in December 1932 he wrote to his friend Claude Arrieu about a letter from another musician, Jacques Porte, outlining plans for a new society to be called Les Jeunes Musiciens Français.

Messiaen agreed to become its vice-president, but nothing seems to have come of the project. Six months later, in June 1933, he had a frustrating meeting with Roger Désormière on behalf of the composers he described to Arrieu as ‘les quatre’, all of them Dukas pupils: Elsa Barraine, the recently-deceased Jean Cartan, Arrieu and Messiaen himself; during the early 1930s Messiaen and Arrieu organised concerts featuring all four composers.”

Finally, we’re getting a connection with the Bourbaki group! Norbert Dufourcq mentioned it already in his comment “Messiaen was also a good friend of Jean Cartan (himself a composer, and Henri’s brother)”. Henri Cartan was one of the first Bourbakis and an excellent piano player himself.

Finally, we’re getting a connection with the Bourbaki group! Norbert Dufourcq mentioned it already in his comment “Messiaen was also a good friend of Jean Cartan (himself a composer, and Henri’s brother)”. Henri Cartan was one of the first Bourbakis and an excellent piano player himself.

The Cartan family picture on the right : standing from left to right, father Elie Cartan (one of the few older French mathematicians respected by the Bourbakis), Henri and his mother Marie-Louise. Seated, the younger children, from left to right : Louis, Helene (who later became a mathematician, herself) and the composer Jean Cartan, who sadly died very young from tuberculoses in 1932…

The december 1934 revolution in French music at the Schola Cantorum, instigated by Messiaen and followers, was the culmination of a process that started a few years before when Jean Cartan was among the circle of revolutionados. Because Messiaen was a fiend of the Cartan family, they surely must have been aware of the events at the Schola (or because it was merely a block away from the ENS), and, the musicians’ revolt may very well have been an example to follow for the first Bourbakis…(?!)

Anyway, we now know the intended meaning of the line “with lemmas sung by the Scholia Cartanorum” on the wedding-invitation. Cartanorum is NOT (as I claimed last time) bad Latin for ‘Cartesiorum’, leading to Descartes and the Saint-Germain-des-Pres church, but is in fact passable Latin (plur. gen.) of CARTAN(us), whence the translation “with lemmas sung by the school of the Cartans”. There’s possibly a double pun intended here : first, a reference to (father) Cartan’s lemma and, of course, to La Schola where the musical Cartan-family felt at home.

Fine, but does this brings us any closer to the intended place of the Bourbaki-Petard wedding? Well, let’s reconsider the hidden ‘clues’ we discovered last time : the phrase “They will receive the trivial isomorphism from P. Adic, of the Order of the Diophantines” might suggest that the church belongs to a a religious order and is perhaps an abbey- or convent-church and the phrase “the organ will be played by Monsieur Modulo” requires us to identify this mysterious Mister Modulo, because Norbert Dufourcq rightfully observed :

Fine, but does this brings us any closer to the intended place of the Bourbaki-Petard wedding? Well, let’s reconsider the hidden ‘clues’ we discovered last time : the phrase “They will receive the trivial isomorphism from P. Adic, of the Order of the Diophantines” might suggest that the church belongs to a a religious order and is perhaps an abbey- or convent-church and the phrase “the organ will be played by Monsieur Modulo” requires us to identify this mysterious Mister Modulo, because Norbert Dufourcq rightfully observed :

“note however that in 1939, it wasn’t as common to have a friend-organist perform at a wedding as it is today: the appointed organists, especially at prestigious Paris positions, were much less likely to accept someone play in their stead.”

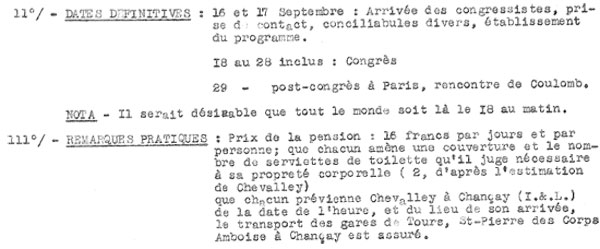

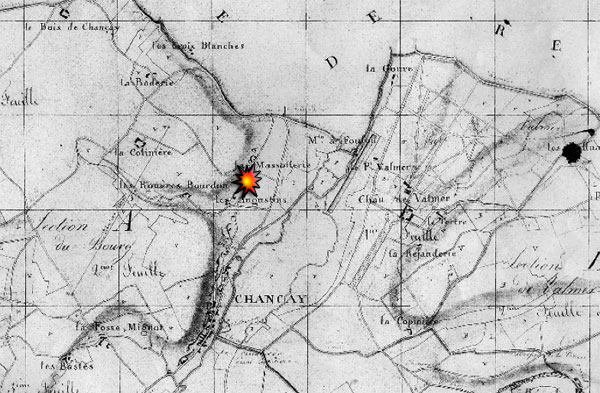

The history of La Schola Cantorum reveals something that might have amused Frank Smithies (remember he was one of the wedding-invitation-composers) : the Schola is located in the Convent(!) of the Brittish Benedictines…

In 1640 some Benedictine monks, on the run after the religious schism in Britain, found safety in Paris under the protection of Cardinal Richelieu and Anne of Austria at Val-de-Grace, where the Schola is now housed.

As is the case with most convents, the convent of the Brittish Benedictines did have its own convent church, now called l’église royale Notre-Dame du Val-de-Grâce (remember that one of the possible interpretations for “of the universal variety” was that the name of the church would be “Notre-Dame”…).

This church is presently used as the concert hall of La Schola and is famous for its … musical organ : “In 1853, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll installed a new organ in the Church of Sainte-geneviève which had been restored in its rôle as a place of worship by Prince President Louis-Napoléon. In 1885, upon the decision of President Jules Grévy, this church once again became the Pantheon and, six years later, according to an understanding between the War and Public Works Departments, the organ was transferred to the Val-de-Grâce, under the supervision of the organ builder Merklin. Beforehand, the last time it was heard in the Pantheon must have been for the funeral service of Victor Hugo.

This church is presently used as the concert hall of La Schola and is famous for its … musical organ : “In 1853, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll installed a new organ in the Church of Sainte-geneviève which had been restored in its rôle as a place of worship by Prince President Louis-Napoléon. In 1885, upon the decision of President Jules Grévy, this church once again became the Pantheon and, six years later, according to an understanding between the War and Public Works Departments, the organ was transferred to the Val-de-Grâce, under the supervision of the organ builder Merklin. Beforehand, the last time it was heard in the Pantheon must have been for the funeral service of Victor Hugo.

In 1927, a raising was carried out by the builder Paul-Marie Koenig, and the inaugural concert was given by André Marchal and Achille Philippe, the church’s organist. Added to the register of historic monument in 1979, Val-de-Grâce’s “ little great organ ”, as Cavaillé-Coll called it, was restored in 1993 by the organ builders François Delangue and Bernard Hurvy.

The organ of Val-de-Grâce is one the rare parisian surviving witnesses of the art of Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, an instrument that escaped abusive and definitive transformations or modernizations. This explain why, in spite of its relatively modest scale, this organ enjoys quite a reputation, and this, as far as the United States.”

By why would the Val-de-Grace organiste at the time Achille Philip, “organiste titulaire du Val-de-Grâce de 1903 à 1950 et professeur d’orgue et d’harmonie à la Schola Cantorum de 1904 à 1950”, be called ‘Mister Modulo’ in the wedding-invitations line “L’orgue sera tenu par Monsieur Modulo”???

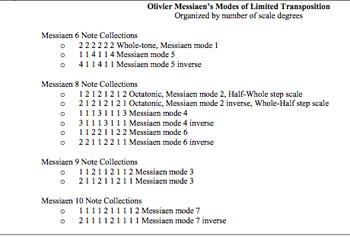

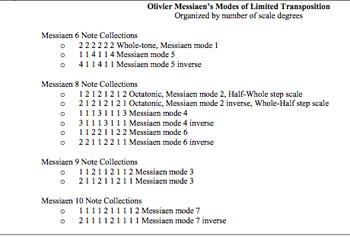

Again, the late Norbert Dufourcq comes to our rescue, proposing a good candidate for ‘Monsieur Modulo’ : “As for “modulo”, note that the organist at Notre-Dame at that time, Léonce de Saint-Martin, was also the composer of a “Suite Cyclique”, though I admit that this is just wordplay: there is nothing “modular” about this work. Maybe a more serious candidate would be Olivier Messiaen (who was organist at the Église de la Trinité): his “modes à transposition limitée” are really about Z/12Z→Z/3Z and Z/12Z→Z/4Z. “

Messiaen’s ‘Modes of limited transposition’ were compiled in his book ‘Technique de mon langage musical’. This book was published in Paris by Leduc, as late as 1944, 5 years after the wedding-invitation.

Messiaen’s ‘Modes of limited transposition’ were compiled in his book ‘Technique de mon langage musical’. This book was published in Paris by Leduc, as late as 1944, 5 years after the wedding-invitation.

Still, several earlier works of Messiaen used these schemes, most notably La Nativité du Seigneur, composed in 1935 : “The work is one of the earliest to feature elements that were to become key to Messiaen’s later compositions, such as the extensive use of the composer’s own modes of limited transposition, as well as influence from birdsong, and the meters and rhythms of Ancient Greek and traditional Indian music.”

More details on Messiaen’s modes and their connection to modular arithmetic can be found in the study Implementing Modality in Algorithmic Composition by Vincent Joseph Manzo.

Hence, Messiaen is a suitable candidate for the title ‘Monsieur Modulo’, but would he be able to play the Val-de-Grace organ while not being the resident organist?

Remember, the Val-de-Grace church was the concert hall of La Schola, and its musical organ the instrument of choice for the relevant courses. Now … Olivier Messiaen taught at the Schola Cantorum and the École Normale de Musique from 1936 till 1939. So, at the time of the Bourbaki-Petard wedding he would certainly be allowed to play the Cavaillé-Coll organ.

Perhaps we got it right, the second time around : the Bourbaki-Pétard wedding was held on June 3rd 1939 in the church ‘l’église royale Notre-Dame du Val-de-Grâce’ at 12h?

On the left : Les Jeunes Musiciens Français : André Jolivet on the Piano. Standing from left to right :

On the left : Les Jeunes Musiciens Français : André Jolivet on the Piano. Standing from left to right : Finally, we’re getting a connection with the Bourbaki group! Norbert Dufourcq mentioned it already in his comment “Messiaen was also a good friend of Jean Cartan (himself a composer, and Henri’s brother)”.

Finally, we’re getting a connection with the Bourbaki group! Norbert Dufourcq mentioned it already in his comment “Messiaen was also a good friend of Jean Cartan (himself a composer, and Henri’s brother)”.  Fine, but does this brings us any closer to the intended place of the Bourbaki-Petard wedding? Well, let’s reconsider the hidden ‘clues’ we discovered last time : the phrase “They will receive the trivial isomorphism from P. Adic, of the Order of the Diophantines” might suggest that the church belongs to a a religious order and is perhaps an abbey- or convent-church and the phrase “the organ will be played by Monsieur Modulo” requires us to identify this mysterious Mister Modulo, because Norbert Dufourcq rightfully observed :

Fine, but does this brings us any closer to the intended place of the Bourbaki-Petard wedding? Well, let’s reconsider the hidden ‘clues’ we discovered last time : the phrase “They will receive the trivial isomorphism from P. Adic, of the Order of the Diophantines” might suggest that the church belongs to a a religious order and is perhaps an abbey- or convent-church and the phrase “the organ will be played by Monsieur Modulo” requires us to identify this mysterious Mister Modulo, because Norbert Dufourcq rightfully observed : This church is presently used as the concert hall of La Schola and is famous for its …

This church is presently used as the concert hall of La Schola and is famous for its …  Messiaen’s

Messiaen’s

Let’s consider “Scholia Cartanorum” more closely. It may be Latin, admittedly very bad Latin, for ‘the Scholiums of Cartesius’, that is, ‘of

Let’s consider “Scholia Cartanorum” more closely. It may be Latin, admittedly very bad Latin, for ‘the Scholiums of Cartesius’, that is, ‘of  the abbay church of

the abbay church of