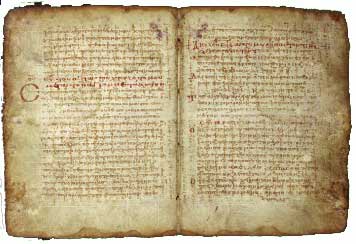

The Archimedes codex is a good read, especially when you are (like me) a failed archeologist. The palimpsest (Greek for ‘scraped again’) is the worlds first Kyoto-approved ‘sustainable writing’. Isn’t it great to realize that one of the few surviving texts by Archimedes only made it because some monks recycled an old medieval parchment by scraping off most of the text, cutting the pages in half, rebinding them and writing a song-book on them…

The Archimedes-text is barely visible as vertical lines running through the song-lyrics. There is a great website telling the story in all its detail.

Contrary to what the books claims I don’t think we will have to rewrite maths history. Didn’t we already know that the Greek were able to compute areas and volumes by approximating them with polygons resp. polytopes? Of course one might view this as a precursor to integral calculus… And then the claim that Archimedes invented ordinal calculus. Sure the Greek knew that there were ‘as many’ even integers than integers… No, for me the major surprise was their theory about the genesis of mathematical notation.

The Greek were pure ASCII mathematicians : they wrote their proofs out in full text. Now, here’s an interesting theory how symbols got into maths… pure laziness of the medieval monks transcribing the old works! Copying a text was a dull undertaking so instead of repeating ‘has the same ratio as’ for the 1001th time, these monks introduced abbreviations like $\Sigma $ instead… and from then on things got slightly out of hand.

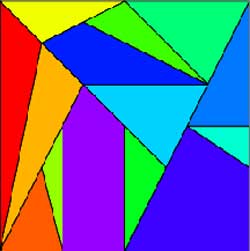

Another great chapter is on the stomachion, perhaps the oldest mathematical puzzle. Just a few pages made in into the palimpsest so we do not really know what (if anything) Archimedes had to say about it, but the conjecture is that he was after the number of different ways one could make a square with the following 14 pieces

People used computers to show that the total number is $17152=2^8 \times 67 $. The 2-power is hardly surprising in view of symmetries of the square (giving $8 $) and the fact that one can flip one of the two vertical or diagonal parts in the alternative description of the square

but I sure would like to know where the factor 67 is coming from… The MAA and UCSD have some good pages related to the stomachion puzzle. Finally, the book also views the problema bovinum as an authentic Archimedes, so maybe I should stick to my promise to blog about it, after all…

One Comment