While this blog is still online, I might as well correct, and add to, previous posts.

Later this week new Twenty One Pilots material is expected, so this might be a good time to add some remarks to a series of posts I ran last summer, trying to find a connection between Dema-lore and the actual history of the Bourbaki group. Here are links to these posts:

- Bourbaki and TØP : East is up

- Bourbaki = Bishops or Banditos?

- Where’s Bourbaki’s Dema?

- Weil photos used in Dema-lore

- Dema2Trench, AND REpeat

- TØP PhotoShop mysteries

- 9 Bourbaki founding members, really?

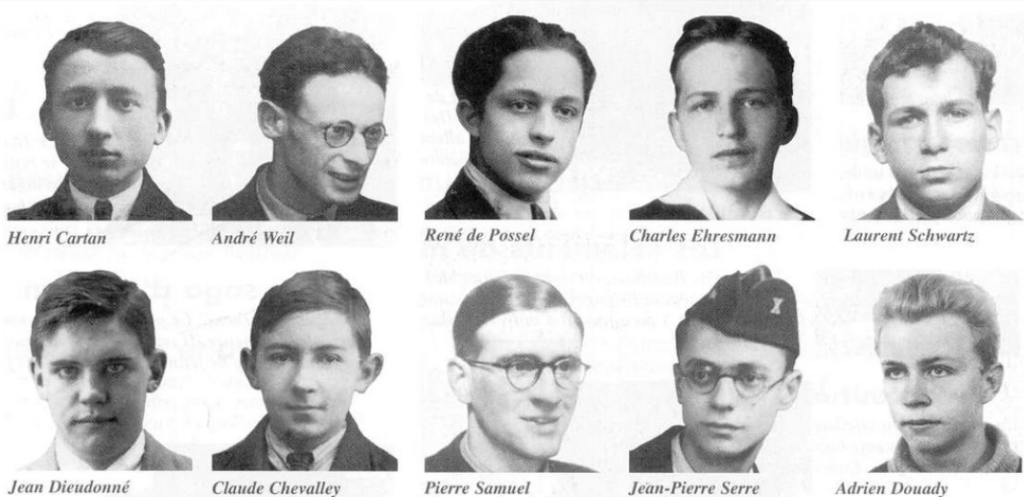

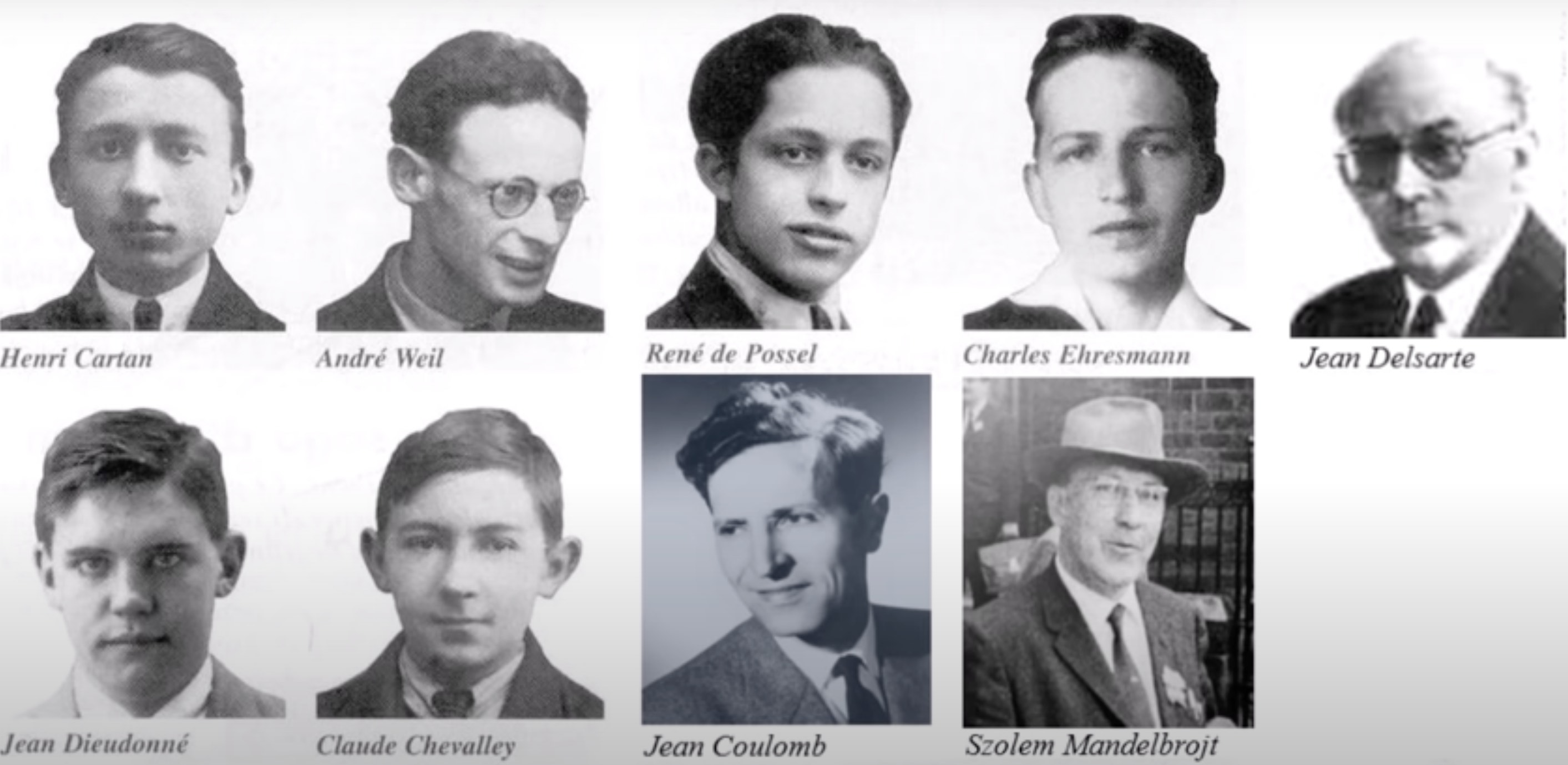

In the post “9 Bourbaki founding members, really?” I questioned Wikipedia’s assertion that there were exactly nine founding members of Nicolas Bourbaki:

- Henri Cartan

- Claude Chevalley

- Jean Coulomb

- Jean Delsarte

- Jean Dieudonne

- Charles Ehresmann

- Szolem Mandelbrojt

- Rene de Possel

- Andre Weil

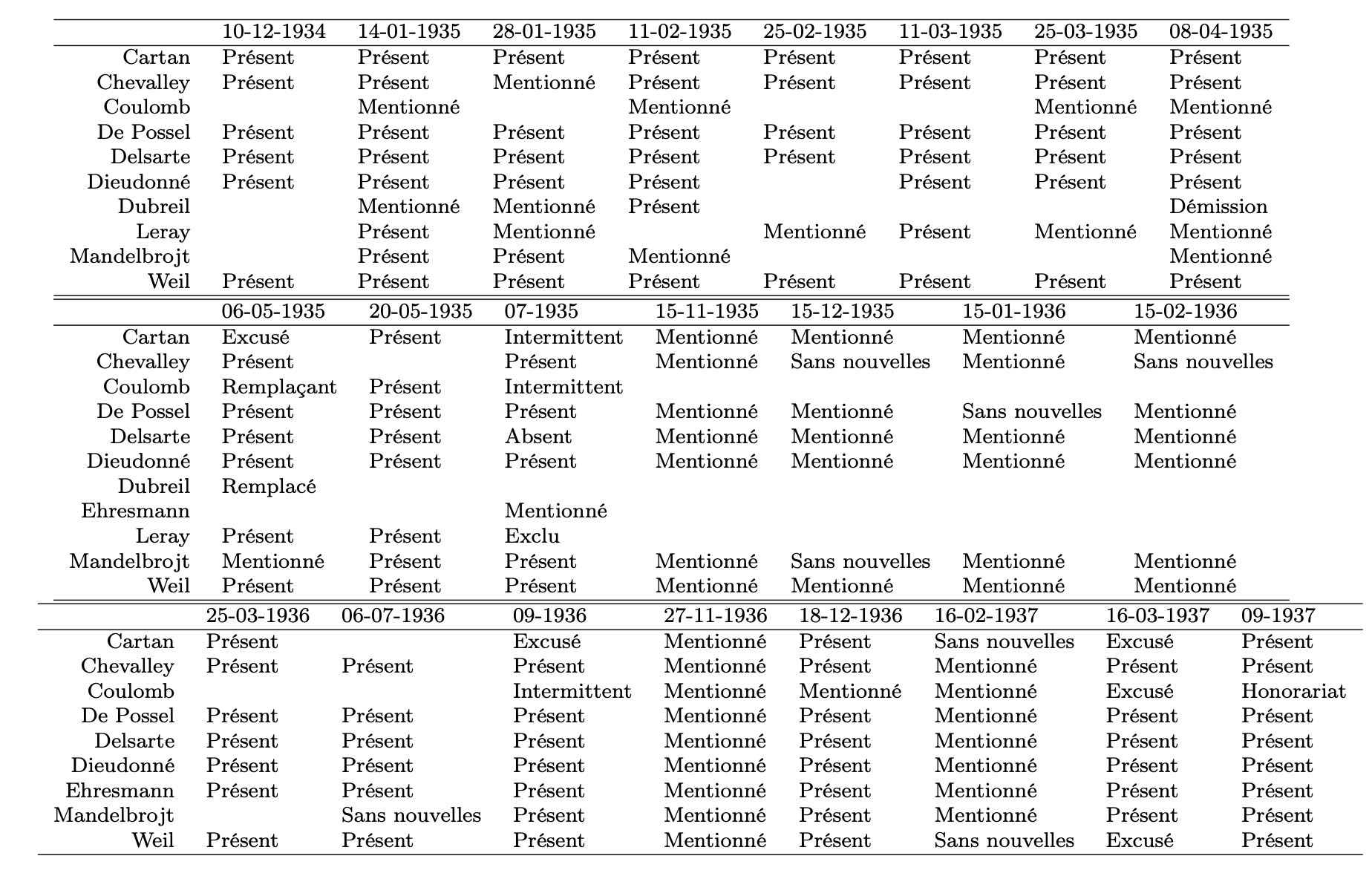

I still stand by the arguments given in that post, but my opinion on this is completely irrelevant. What matters is who the Bourbaki-gang themself deemed worthy to attach their names to their first publication ‘Theorie des Ensembles’ (1939).

But wait, wasn’t the whole point of choosing the name Nicolas Bourbaki for their collective that the actual authors of the books should remain anonymous?

Right, but then I found this strange document in the Bourbaki Archives : awms_001, a preliminary version of the first two chapters of ‘Theorie des Ensembles’ written by Andre Weil and annotated by Rene de Possel. Here’s the title page:

Next to N. Bourbaki we see nine capital letters: M.D.D.D.E.C.C.C.W corresponding to nine AW-approved founding members of Bourbaki: Mandelbrojt, Delsarte, De Possel, Dieudonne, Ehresmann, Chevalley, Coulomb, Cartan and Weil!

What may freak out the Clique is the similarity between the diagram to the left of the title, and the canonical depiction of the nine Bishops of Dema (at the center of the map of Dema) or the cover of the Blurryface album:

In the Photoshop mysteries post I explained why Mandelbrojt and Weil might have been drawn in opposition to each other, but I am unaware of a similar conflict between either of the three C’s (Cartan, Coulomb and Chevalley) and the three D’s (Delsarte, De Possel and Dieudonne).

So, I’ll have to leave the identification of the nine Bourbaki founding members with the nine Dema Bishops as a riddle for another post.

The second remark concerns the post Where’s Bourbaki’s Dema?.

In that post I briefly suggested that DEMA might stand for DEutscher MAthematiker (German Mathematicians), and hinted at the group of people around David Hilbert, Emil Artin and Emmy Noether, but discarded this as “one can hardly argue that there was a self-destructive attitude (like Vialism) present among that group, quite the opposite”.

At the time, I didn’t know about Deutsche Mathematik, a mathematics journal founded in 1936 by Ludwig Bieberbach and Theodor Vahlen.

Deutsche Mathematik is also the name of a movement closely associated with the journal whose aim was to promote “German mathematics” and eliminate “Jewish influence” in mathematics. More about Deutsche Mathematik can be found on this page, where these eight mathematicians are mentioned in connection with it:

- Ludwig Bieberbach

- Theodor Vahlen

- Oswald Teichmuller

- Erhard Tornier

- Helmut Hasse

- Wilhelm Suss

- Helmut Wielandt

- Gustav Doetsch

Perhaps one can add to this list:

Whether DEutsche MAthematik stands for DEMA, and which of these German mathematicians were its nine bishops might be the topic of another post. First I’ll have to read through Sanford Segal’s Mathematicians under the Nazis.

Added February 29th:

The long awaited new song has now surfaced:

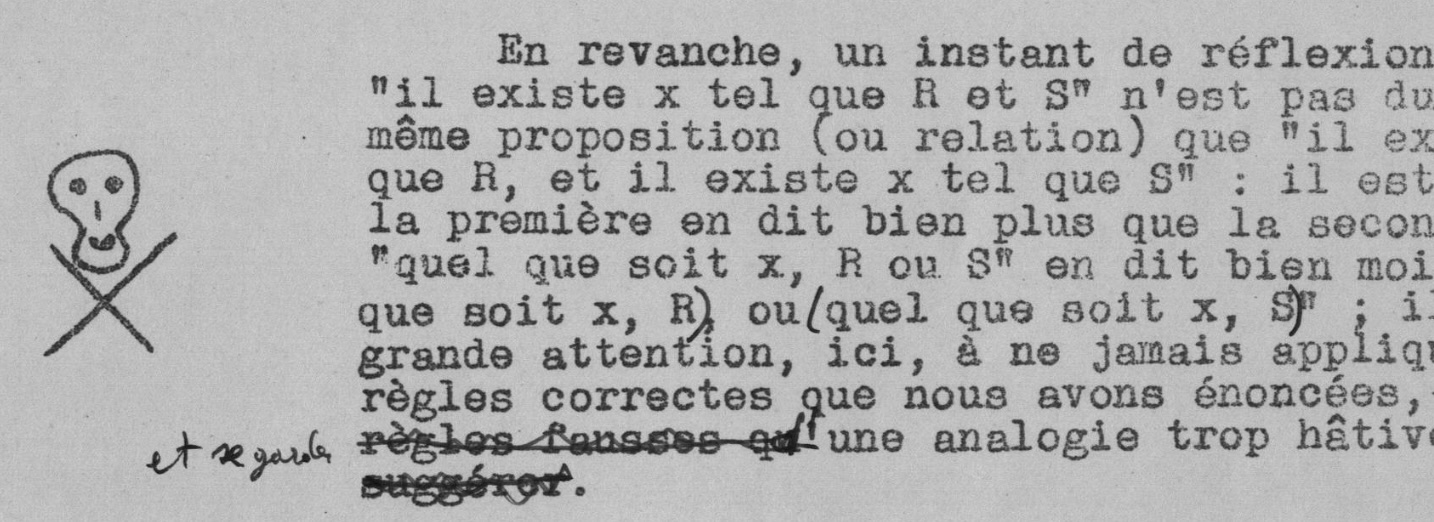

I’ve only watched it once, but couldn’t miss the line “I fly by the dangerous bend symbol“.

Didn’t we all fly by them in our first readings of Bourbaki…

(Fortunately the clique already spotted that reference).

No intention to freak out clikkies any further, but in the aforementioned Weil draft of ‘Theorie des Ensembles’ they still used this precursor to the dangerous bend symbol

Skeletons anyone?

Leave a Comment