A few weeks more of (heavy) teaching ahead, and then I finally hope to start on a project, slumbering for way too long: to write a book for a broader audience.

Prepping for this I try to read most of the popular math-books hitting the market.

The latest two explore how the internet changed the way we discuss, learn and do mathematics. Think Math-Blogs, MathOverflow and Polymath.

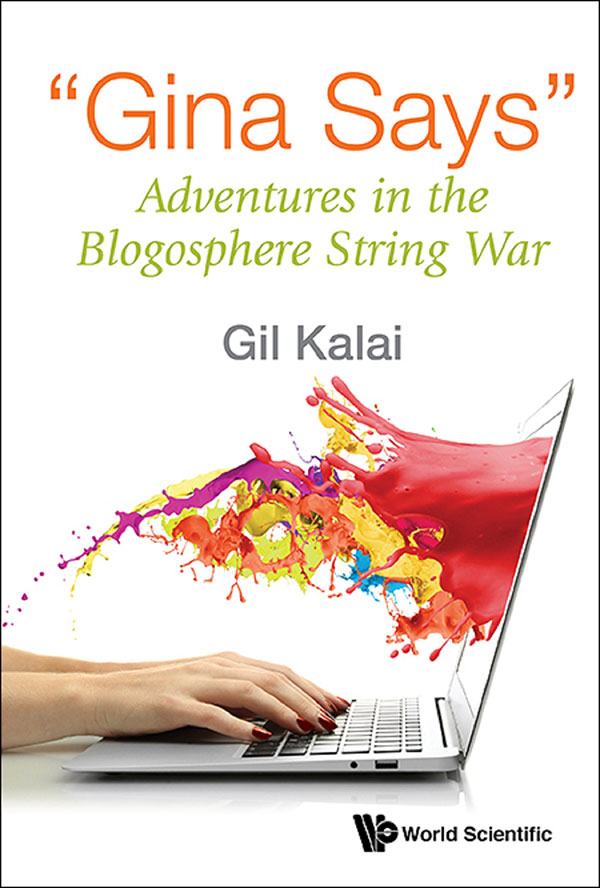

‘Gina says’, Adventures in the Blogosphere String War

The ‘string wars’ started with the publication of the books by Peter Woit:

Not even wrong: the failure of string theory and the search for unity in physical law

and Lee Smolin:

The trouble with physics: the rise of string theory, the fall of a science, and what comes next.

In the summer of 2006, Gil Kalai got himself an extra gmail acount, invented the fictitious ‘Gina’ and started commenting (some would argue trolling) on blogs such as Peter Woit’s own Not Even Wring, John Baez and Co.’s the n-Category Cafe and Clifford Johnson’s Asymptotia.

Gil then copy-pasted Gina’s comments, and the replies they provoked, into a leaflet and put it on his own blog in June 2009: “Gina says”, Adventures in the Blogosphere String War.

Back then, it was fun to waste an afternoon re-reading all of this, and I wrote about it here:

Now here’s an idea (June 2009)

Gina says, continued (August 2009)

With only minor editing, and including some drawings by Gil’s daughter, these leaflets have now resurfaced as a book…?!

After more than 10 years I had hoped that Gil would have taken this test-case to say some smart things about the math-blogging scene and its potential to attract more people to mathematics, or whatever.

In 2009 I wrote:

“Having read the first 20 odd pages in full and skimmed the rest, two remarks : (1) it shouldn’t be too difficult to borrow this idea and make a much better book out of it and (2) it raises the question about copyrights on blog-comments…”

Closing the gap: the quest to understand prime numbers

I can hear you sigh, but no, this is not yet another prime number book.

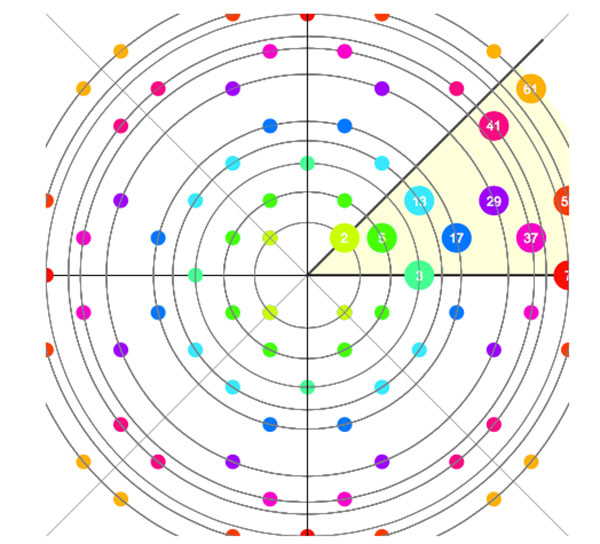

In May 2013, Yitang Zhang startled the mathematical world by proving that there are infinitely many prime pairs, each no more than 70.000.000 apart.

Perhaps a small step towards the twin prime conjecture but it was the first time someone put a bound on this prime gap.

Vicky Neal‘s book tells the story of closing this gap. In less than a year the bound of 70.000.000 was brought down to 246.

If you’ve read all popular prime books, there are a handful of places in the book where you might sigh: ‘oh no, not that story again’, but by far the larger part of the book explains exciting results on prime number progressions, not found anywhere else.

Want to know about sieve methods?

Which results made Tim Gowers or Terry Tao famous?

What is Szemeredi’s theorem or the Hardy-Littlewood circle method?

Ever heard about the Elliot-Halberstam or the Erdos-Turan conjecture? The work by Tao on Erdos discrepancy problem or that of James Maynard (and Tao) on closing the prime gap?

Closing the gap is the book to read about all of this.

But it is much more.

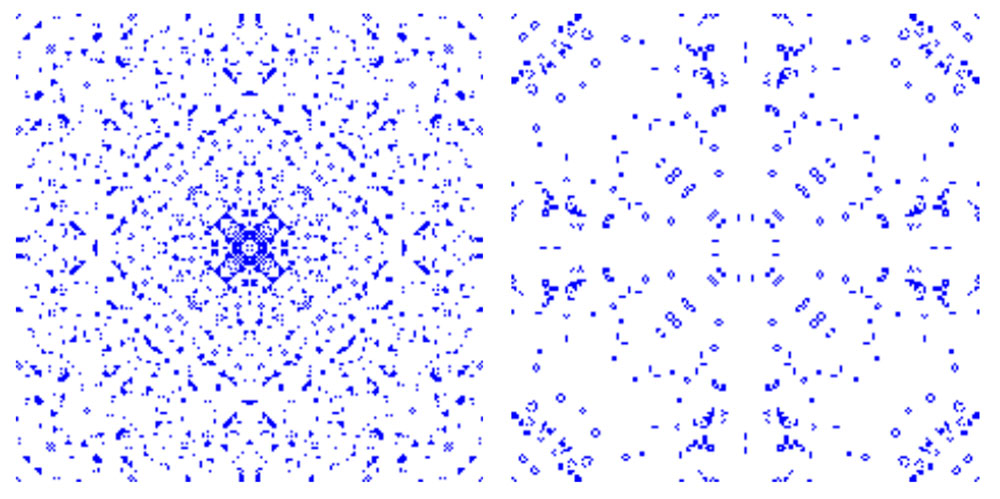

It tells about the origins and successes of the Polymath project, and details the progress made by Polymath8 on closing the gap, it gives an insight into how mathematics is done, what role conferences, talks and research institutes a la Oberwolfach play, and more.

Looking for a gift for that niece of yours interested in maths? Look no further. Closing the gap is a great book!

One Comment