I was running a bachelor course on representations of finite groups and a master course on simple (mainly sporadic) groups until Corona closed us down. Perhaps these blog-posts can be useful to some.

A curious fact, with ripple effect on Mathieu sporadic groups, is that the symmetric group S6 has an automorphism ϕ, different from an automorphism by conjugation.

In the course notes the standard approach was given, based on the 5-Sylow subgroups of S5.

Here’s the idea. Let S6 act by permuting 6 elements and consider the subgroup S5 fixing say 6. If such an odd automorphism ϕ would exist, then the subgroup ϕ(S5) cannot fix one of the six elements (for then it would be conjugated to S5), so it must act transitively on the six elements.

The alternating group A5 is the rotation symmetry group of the icosahedron

Any 5-Sylow subgroup of A5 is the cyclic group C5 generated by a rotation among one of the six body-diagonals of the icosahedron. As A5 is normal in S5, also S5 has six 5-Sylows.

More lowbrow, such a subgroup is generated by a permutation of the form (1,2,a,b,c), of which there are six. Good old Sylow tells us that these 5-Sylow subgroups are conjugated, giving a monomorphism

S5→Sym({5−Sylows})≃S6

and its image H is a subgroup of S6 of index 6 (and isomorphic to S5) which acts transitively on six elements.

Left multiplication gives an action of S6 on the six cosets S6/H={σH : σ∈S6}, that is a groupmorphism

ϕ:S6→Sym({σH})=S6

which is our odd automorphism (actually it is even, of order two). A calculation shows that ϕ sends permutations of cycle shape 2.14 to shape 23, so can’t be given by conjugation (which preserves cycle shapes).

An alternative approach is given by Noah Snyder in an old post at the Secret Blogging Seminar.

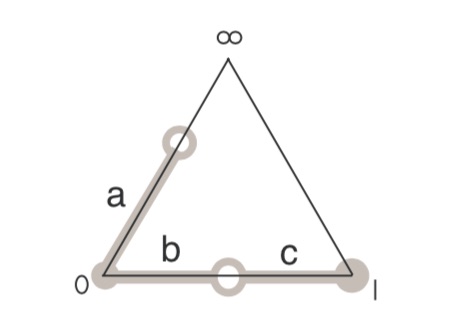

Here, we like to identify the six points {a,b,c,d,e,f} with the six points {0,1,2,3,4,∞} of the projective line P1(F5) over the finite field F5.

There are 6! different ways to do this set-theoretically, but lots of them are the same up to an automorphism of P1(F5), that is an element of PGL2(F5) acting via Mobius transformations on P1(F5).

PGL2(F5) acts 3-transitively on P1(F5) so we can fix three elements in each class, say a=0,b=1 and f=∞, leaving six different ways to label the points of the projective line

abcdef101234∞201243∞301324∞401342∞501423∞601432∞

A permutation of the six elements {a,b,c,d,e,f} will result in a permutation of the six classes of P1(F5)-labelings giving the odd automorphism

ϕ:S6=Sym({a,b,c,d,e,f})→Sym({1,2,3,4,5,6})=S6

An example: the involution (a,b) swaps the points 0 and 1 in P1(F5), which can be corrected via the Mobius-automorphism t↦1−t. But this automorphism has an effect on the remaining points

2↔43↔3∞↔∞

So the six different P1(F5) labelings are permuted as

ϕ((a,b))=(1,6)(2,5)(3,4)

showing (again) that ϕ is not a conjugation-automorphism.

Yet another, and in fact the original, approach by James Sylvester uses the strange terminology of duads, synthemes and synthematic totals.

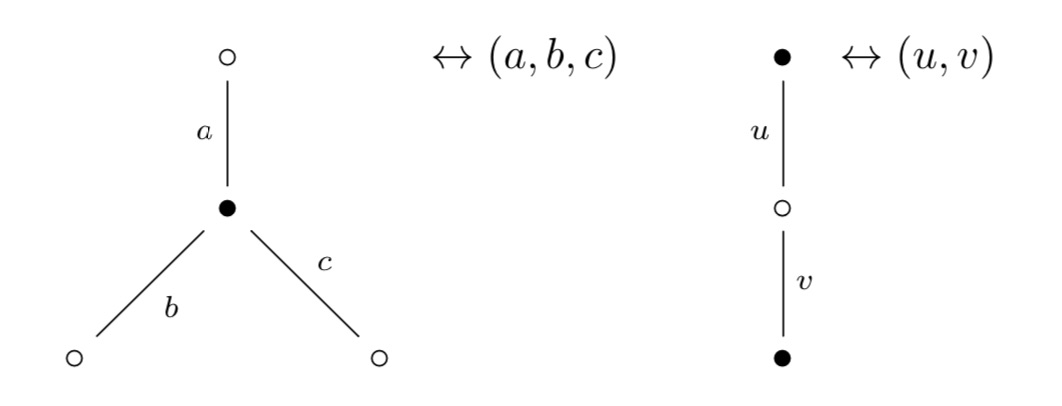

- A duad is a 2-element subset of {1,2,3,4,5,6} (there are 15 of them).

- A syntheme is a partition of {1,2,3,4,5,6} into three duads (there are 15 of them).

- A (synthematic) total is a partition of the 15 duads into 5 synthemes, and they are harder to count.

There’s a nice blog-post by Peter Cameron on this, as well as his paper From M12 to M24 (after Graham Higman). As my master-students have to work their own way through this paper I will not spoil their fun in trying to deduce that

- Two totals have exactly one syntheme in common, so synthemes are ‘duads of totals’.

- Three synthemes lying in disjoint pairs of totals must consist of synthemes containing a fixed duad, so duads are ‘synthemes of totals’.

- Duads come from disjoint synthemes of totals in this way if and only if they share a point, so points are ‘totals of totals’

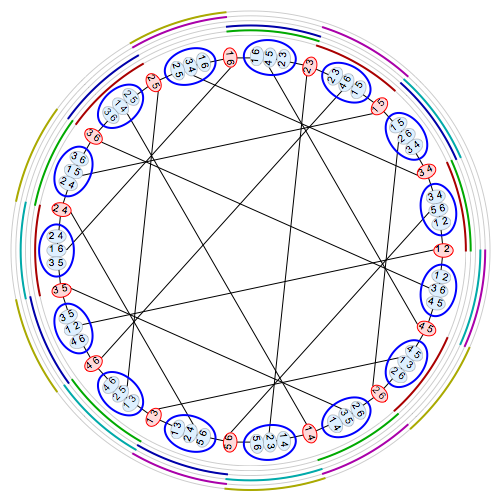

My hint to the students was “Google for John Baez+six”, hoping they’ll discover Baez’ marvellous post Some thoughts on the number 6, and in particular, the image (due to Greg Egan) in that post

which makes everything visually clear.

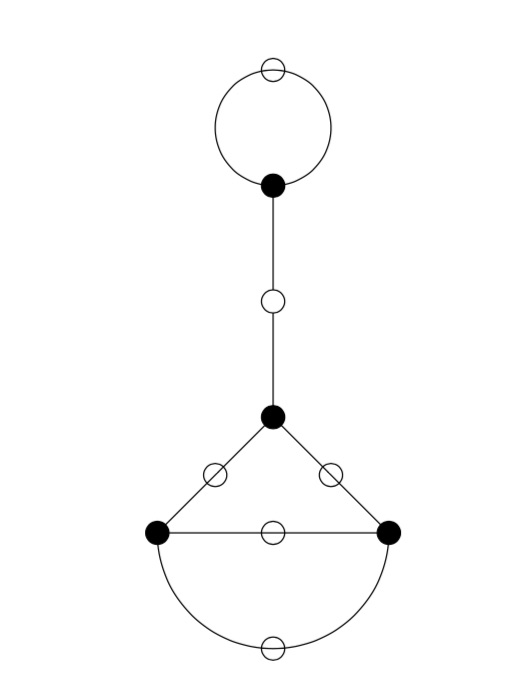

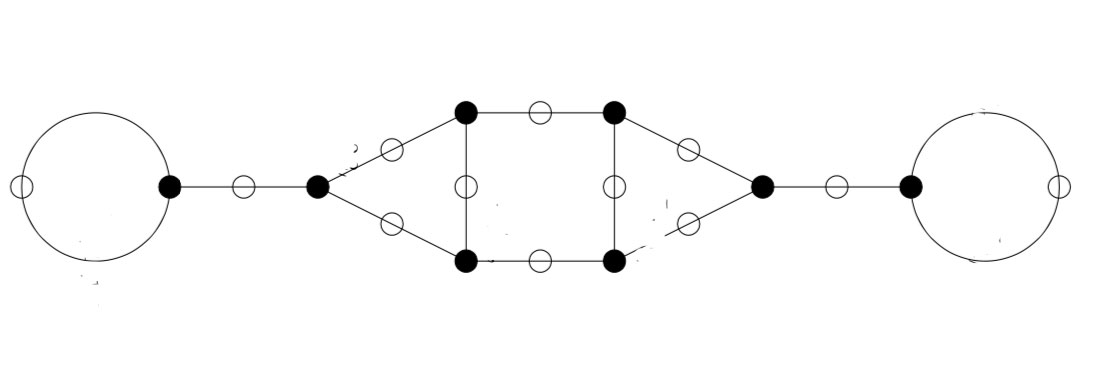

The duads are the 15 red vertices, the synthemes the 15 blue vertices, connected by edges when a duad is contained in a syntheme. One obtains the Tutte-Coxeter graph.

The 6 concentric rings around the picture are the 6 synthematic totals. A band of color appears in one of these rings near some syntheme if that syntheme is part of that synthematic total.

If {t1,t2,t3,t4,t5,t6} are the six totals, then any permutation σ of {1,2,3,4,5,6} induces a permutation ϕ(σ) of the totals, giving the odd automorphism

ϕ:S6=Sym({1,2,3,4,5,6})→Sym({t1,t2,t3,t4,t5,t6})=S6

.jpg)