Today, we will expand the game of Nimbers to higher dimensions and do some transfinite Nimber hacking.

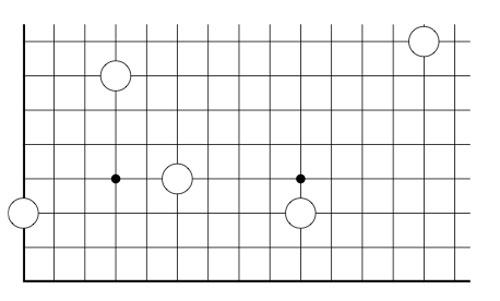

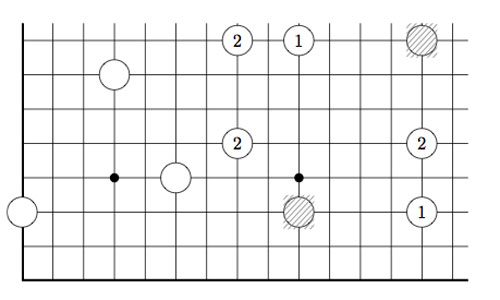

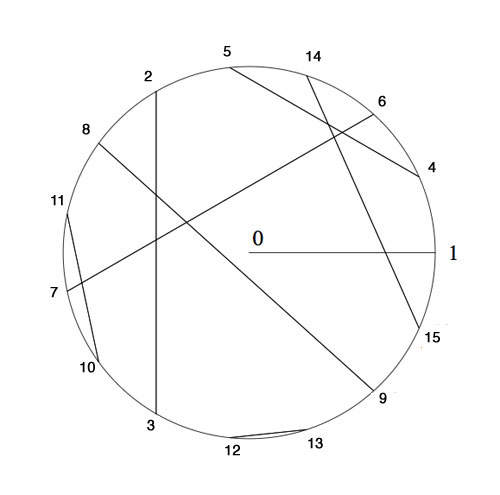

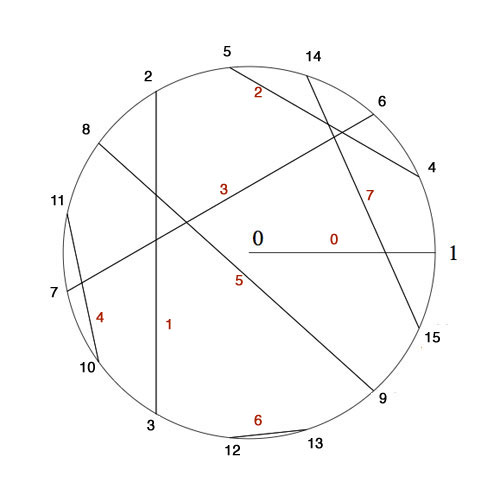

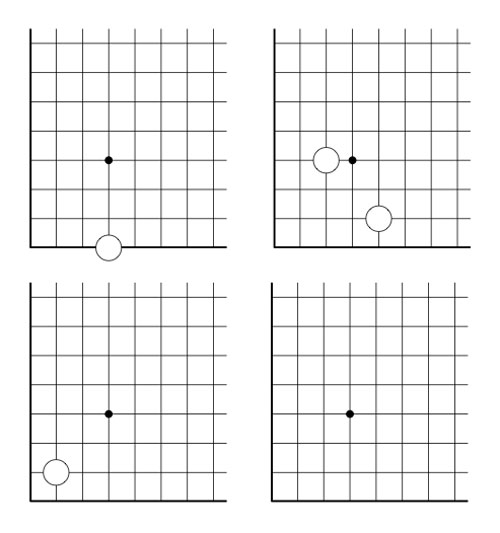

In our identification between $\mathbb{F}_{16}^* $ and 15-th roots of unity, the number 8 corresponds to $\mu^6 $, whence $\sqrt{8}=\mu^3=14 $. So, if we add a stone at the diagonal position (14,14) to the Nimbers-position of last time

we get a position of Nim-value 0, that is, winnable for the second player. In fact, this is a universal Nimbers-truth :

Either the 2nd player wins a Nimbers-position, or one can add one stone to the diagonal such that it becomes a 2nd player win.

The proof is elementary : choose a Fermat 2-power such that all stones have coordinates smaller than $2^{2^n} $. If the Nim-value of the position isn’t zero, it corresponds to a unit $\alpha \in \mathbb{F}_{2^{2^n}}^* $. Now,the Frobenius map $x \mapsto x^2 $ is an automorphism of any finite field of characteristic two, so the square root $\sqrt{\alpha} $ also belongs to $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^n}} $, done!

3-dimensional Nimbers is played in the first octant of the integral lattice $\mathbb{Z}^3 $ by placing a finite number of balls at places $~(a,b,c) \in \mathbb{N}^3 $ with $abc \geq 1 $.

Moves are defined by replacing the rectangular-rule of the two-dimensional version by the cuboid-rule : take a cuboid with faces parallel to the coordinate planes whose corner of maximal distance from the origin is one of the balls in the position. Remove that ball and add new balls to the unoccupied corners and remove balls at occupied corners.

Here, we allow the corner-points to have zero as some of its coordinates, but these balls are considered dead in the game. As in the two-dimensional game, this cuboid-rule encompasses several legal moves depending on the number of corners in the cuboid having zero-coordinates.

Again, it follows by induction that the Nim-value of a ball placed at position $~(a,b,c) $ is equal to the Nim-multiplication $a \otimes b \otimes c $ and we can calculate the Nim-value of a 3-dimensional Nimbers-position by computing in a suitable field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^n}} $. (The extension to higher dimensions is now obvious)

Does 3-dimensional Nimbers satisfy the ‘universal truth’, that is, can one make any position a 2nd player win by adding at most one stone to the body-diagonal?

The previous argument fails. As $\mathbb{F}_4^* $ is the cyclic group of order three, the 3rd roots of unity in $\overline{\mathbb{F}_2} $ correspond to the numbers 1,2 and 3, so the map $x \mapsto x^3 $ cannot be a bijection on any of the finite fields $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^n}} $.

But then, perhaps, a third root is added by going to a larger such field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^N}} $? Well, not quite. Take for example 2, then $\sqrt[3]{2} \notin \mathbb{F}_{2^{2^N}} $. (2 has order 3 in $\mathbb{F}_4 $ and so its 3rd root must have order 9, but 9 does not divide any number of the form $2^{2^N}-1 $ as the Fermat-powers mod 9 can only be 4 or 7).

In fact one can show that this also holds for any number not in the image of the cubing-map in some $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^n}} $ as

$\mathbb{N}={ 0,1,2,\ldots } = \cup_N \mathbb{F}_{2^{2^N}} $

with Nim-addition and multiplication is the quadratic closure of $\mathbb{F}_2 $ (see for example ONAG).

The situation changes if we allow ourself to play transfinite Nimbers, with the same rules as before but now we allow the stone, balls etc. to be placed at points of which the coordinates are not restricted to $\mathbb{N}_+ = \{ 1,2,3,\ldots \} $ but may vary over $[\beta]_+ $ for some ordinal $\beta $ where $[\beta]_+=\{ 1,2,\ldots,\omega,\omega+1,\ldots \} $ is the set of all ordinals smaller than $\beta $.

In transfinite 3-dimensional Nimbers the ‘universal truth’ still holds, provided we play it on a cube of sizes $[\omega^{\omega}]_+ $. In particular we have that $\sqrt[3]{2}=\omega $ by the simplicity rule (see ONAG or the Conway’s nim-arithmetic post)

In general, n-dimensional transfinite Nimbers played on an n-gid of sizes $[\omega^{\omega^{\omega}}]_+ $ satisfies the universal truth : either a position is a 2nd player win or it becomes one by adding one n-ball to a diagonal position! (this follows immediately because $[\omega^{\omega^{\omega}}] $ with Nim-addition and multiplication is isomorphic to the algebraic closure of $\mathbb{F}_2 $).

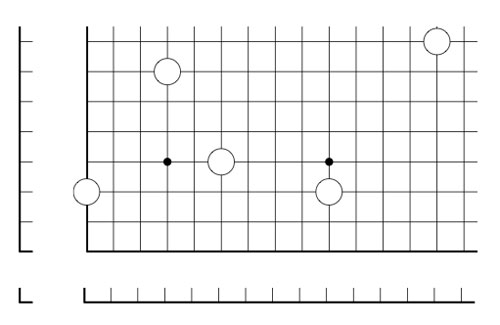

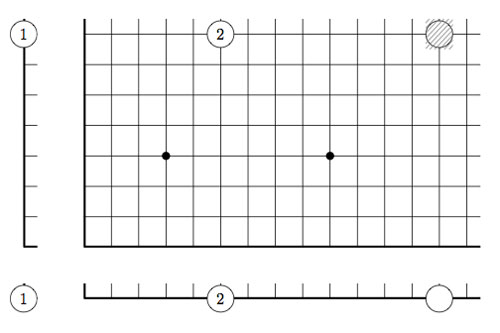

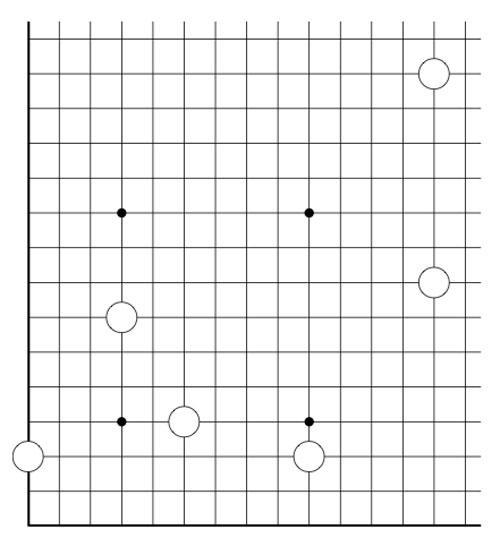

2-dimensional transfinite Nimbers is still pretty playable. Below a position on a $\omega.2 $-board with stones as positions $~(2,2),(4,\omega),(\omega+2,\omega+3) $ and $~(\omega+4,\omega+1) $

Give a winning move for the first player!

Leave a Comment