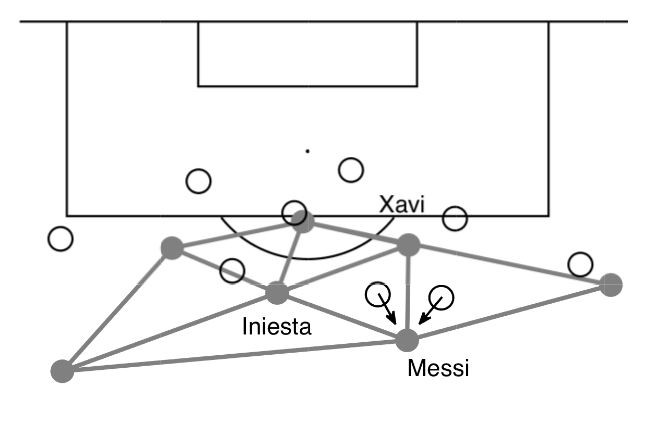

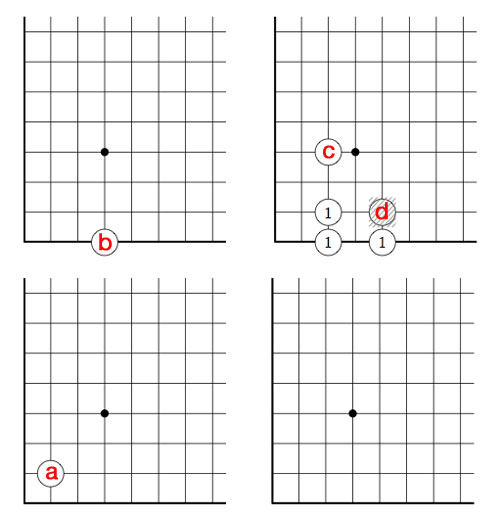

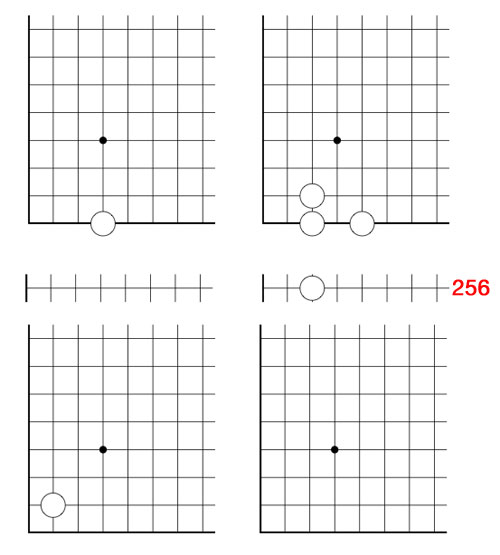

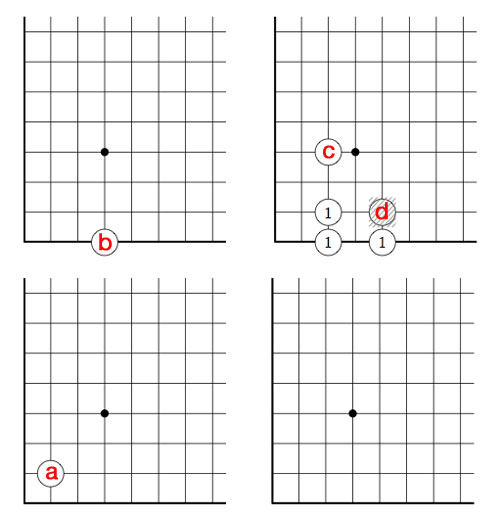

Last time we introduced the game of transfinite Nimbers and asked a winning move for the transfinite game with stones a at position $~(2,2) $, b at $~(4,\omega) $, c at $~(\omega+2,\omega+3) $ and d at position $~(\omega+4,\omega+1) $.

Above is the unique winning move : we remove stone d and by the rectangle-rule add three new stones, marked 1. We only need to compute in finite fields to solve this and similar problems.

First note that the largest finite number occuring in a stone-coordinate is 4, so in this case we can perform all calculations in the field $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^2}}(\omega) = \mathbb{F}_{2^{12}} $ where (as before) we identify $\mathbb{F}_{2^{2^2}} = { 0,1,2,\ldots,15 } $ and we have seen that $\omega^3=2 $ (for ease of notation all Nim-additions and Nim-multiplications are denoted this time by + and x instead of $\oplus $ and $\otimes $ as we did last time, so for example $\omega^3 = \omega \otimes \omega \otimes \omega $).

If you’re not nimble with the Nim-tables, you can check all calculations in SAGE where we define this finite field via

sage: R.< x,y,z>=GF(2)[]

sage: S.< t,f,o>=R.quotient((x^2+x+1,y^2+y+x,z^3+x))

and we can now calculate in $\mathbb{F}_{2^{12}} $ using the symbols t for Two, f for Four and o for $\omega $. For example, we have seen that the nim-value of a stone is the nim-multiplication of its coordinates

sage: t*t

t + 1

sage: f*o

f*o

sage: (o+t)*(o+t+1)

o^2 + o + 1

sage: (o+f)*(o+1)

f*o + o^2 + f + o

That is, the nim-value of stone a is 3, stone b is $4 \times \omega $, stone c is $\omega^2+\omega+1 $ and finally that of stone d is equal to $\omega^2+5 \times \omega +4 $.

By adding them up, the nim-value of the original position is a finite number : 6. Being non-zero we know that the 2nd player has a winning strategy.

Just as in ordinary nim, we compare the value of a stone to the sum of the values of the other stones, to determine the stone we will play. These sums are for the four stones : 5 for a, $4 \times \omega+6 $ for b, $\omega^2+\omega+7 $ for c and $\omega^2+5 \times \omega+2 $ for d. There is only one stone where this sum is smaller than the stone-value, so we know we have to make our move with stone d.

By the Nimbers-rule we need to find a rectangle with top-right hand corner $~(\omega+4,\omega+1) $ and lower-left hand corner $~(u,v) $ such that the values of the three new corners adds up to $\omega^2+5 \times \omega+2 $, that is we have to solve

$u \times v + u \times (\omega+1) + (\omega+4)\times v = \omega^2+5 \times \omega+2 $

where u and v are ordinals smaller than $\omega+4 $ and $\omega+1 $. u and v cannot be both finite, for then we wouldn’t obtain a $\omega^2 $ term. Similarly (u,v) cannot be of the form $~(u,\omega) $ with u finite because then the left-hand sum would be $\omega^2+4 \times \omega + u $ and likewise it cannot be of the form $~(\omega+i,v) $ with i and v finite as then the coefficient of $\omega $ in the left-hand sum will be i+1 and we cannot take i equal to 4.

The only remaining possibility is that (u,v) is of the form $~(\omega+i,\omega) $ with i finite, in which case the left-hand sum equals $~\omega^2+ 5 \times \omega + i $ whence i=2 and we have found our unique winning move!

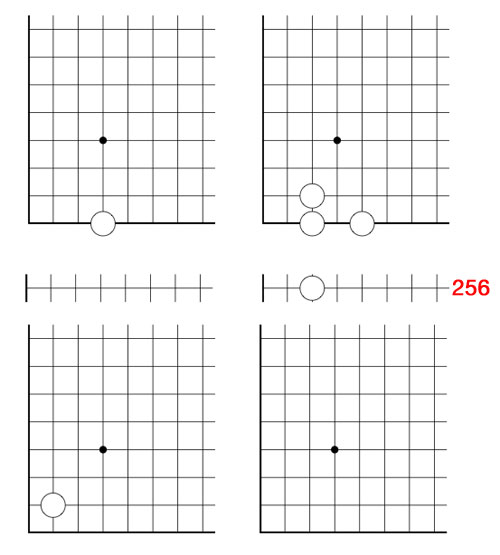

But, our opponent can make life difficult by forcing us to compute in larger and larger finite fields. For example, if she would move next by dropping the c stone down to the 256-th row, what would be our next move?

(one possible winning move is to remove the stone at $~(\omega+2,\omega) $ and add stones at the three new corners of the rectangle : $~(257,2), (257,\omega) $ and $~(\omega+2,2) $)