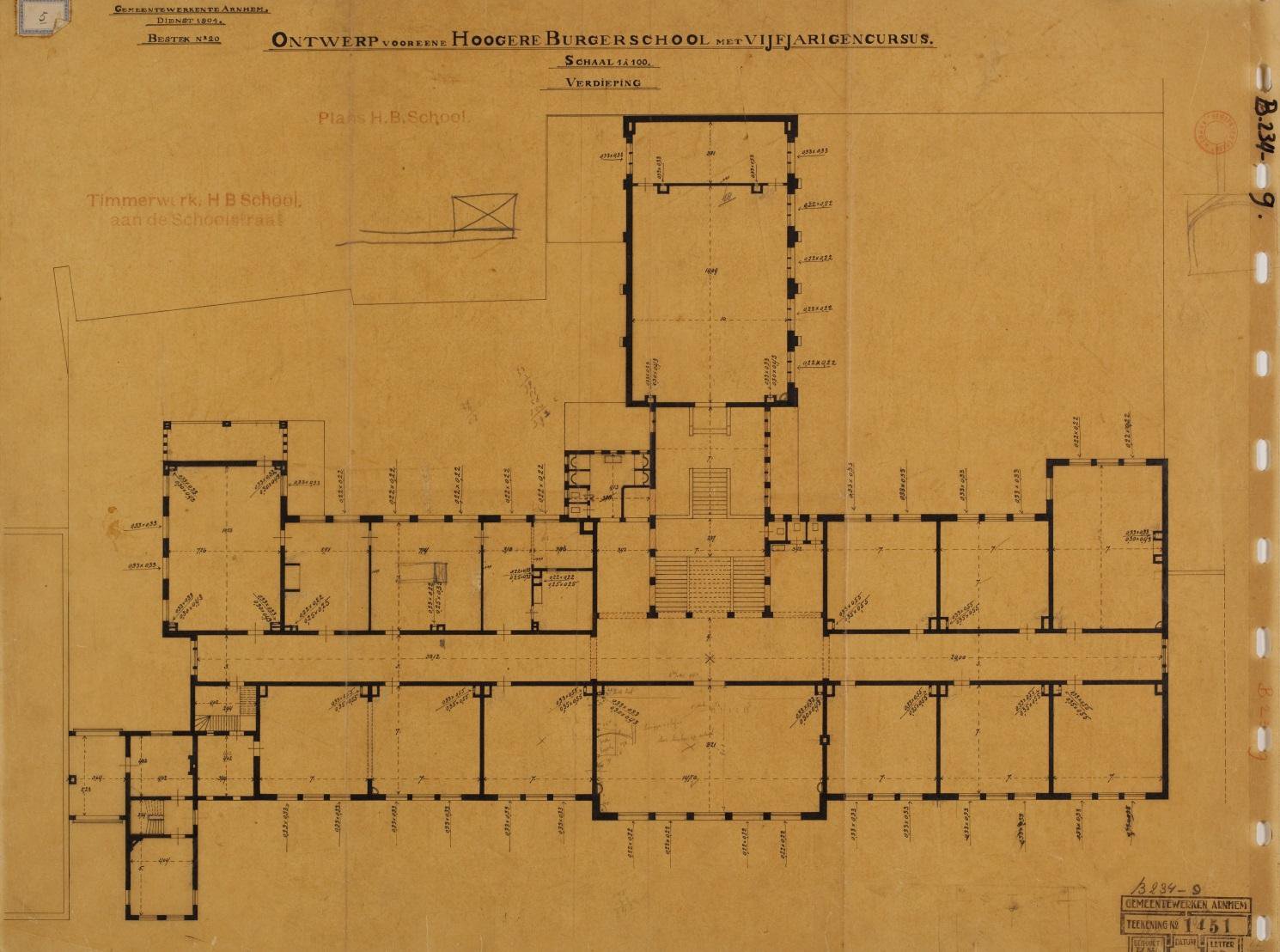

This fall, I’ll be teaching ‘Mathematics for Designers’ to first year students in Architecture.

The past few weeks I’ve been looking around for topics to be included in such as course, relevant to architects/artists (not necessarily to engineers/mathematicians).

One of the best texts I’ve found on this (perhaps in need of a slight update) is the 1986-paper by Jay Kappraff: A course in the mathematics of design. He suggests the following list of topics:

- graph theory

- polyhedra

- tilings of the plane

- three dimensional packings

- proportion and the golden mean

- transformations

- symmetry

- vectors

We all know that an awful lot of math and computation is needed to design a building, but today all of the hardcore use of vectors, equations and transformations is conveniently hidden from the architect’s view by digital design platforms and CAD-programs.

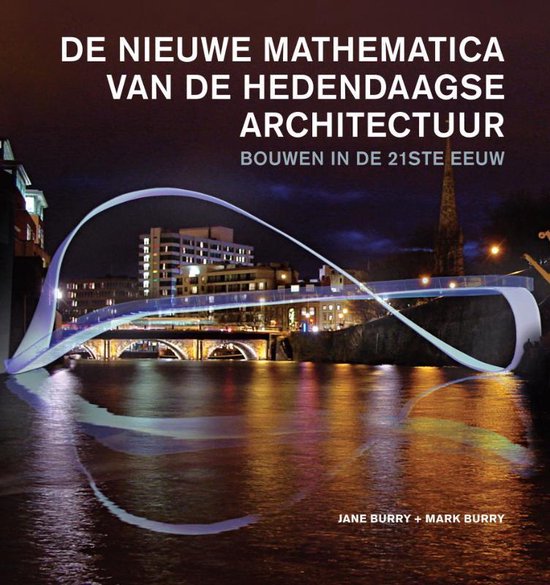

These computational tools offer new creative possibilities, as illustrated in the beautiful book The new mathematics of architecture by Jane Burry and Mark Burry, also available in Dutch with a cover picture of the Möbius bridge in Bristol

In this book, about 50 recent architectural projects are clustered around these topics:

- mathematical surfaces and seriality

- chaos, complexity, emergence

- packings and tilings

- optimization

- topology

- datascapes and multi-dimensionality

In the description of the projects, cool math-topics are (sadly only) touched, including

- Amman tilings

- Aperiodic tilings

- Cellular automata

- Chaos theory

- Danzer packings

- Fractals

- Homology

- Knot theory

- Higher dimensional manifolds

- Minimal surfaces

- NURBS

- Penrose tilings

- Singularity theory

- Voronoi diagrams

- Seifert surfaces

- Quasicrystals

It will take me some time to find a balance between these two approaches. Common themes clearly are

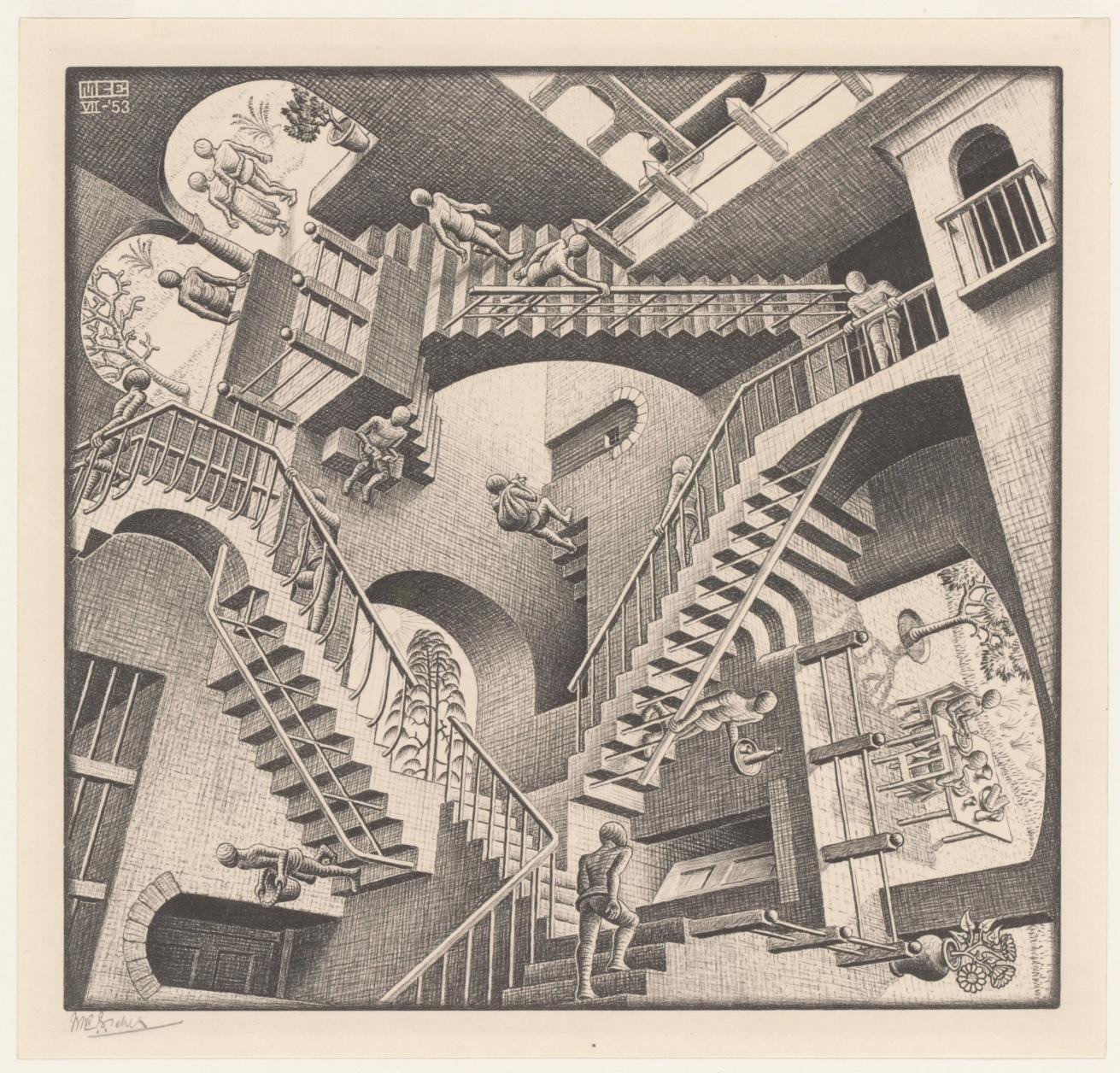

- Shapes : what is possible/impossible in 2D and 3D, and how can mathematics help us to find new exciting shapes (think minimal and Seifert surfaces, knot complements, etc.)

- Symmetry : what is possible/impossible in 2D and 3D, and what can mathematics tell us about new symmetries (think emerging symmetries from aperiodic tilings and quasicrystals)

Over the coming months I’ll be writing the course notes and may post about it here. For this reason I’ve included a new category DesignerMaths.

If you have suggestions, please let me know.

2 Comments