My favourite tags on MathOverflow are big-lists, big-picture, soft-question,

reference-request and the like.

Often, answers to such tagged questions contain sound reading advice, style: “road-map to important result/theory X”.

Two more K to go, so let’s spend some more money.

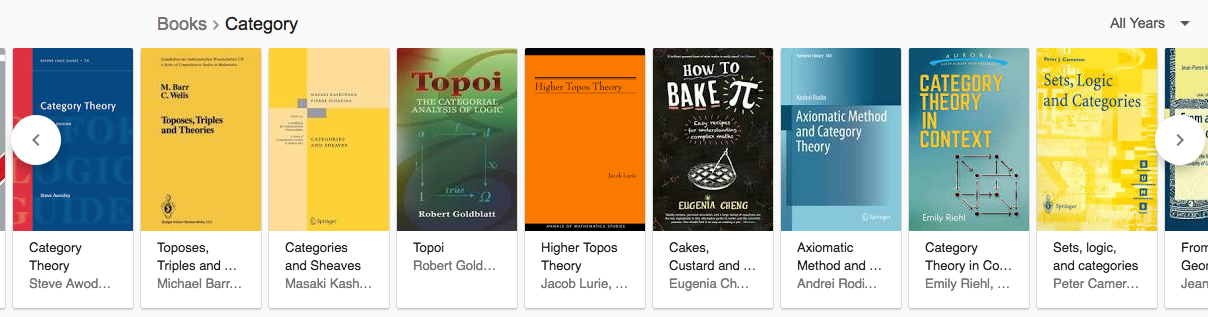

[section_title text=”Category theory”]

One of the problems with my master course on algebraic geometry is that the students are categorical virgins.

They’ve been studying specific categories, functors, natural transformations and more all over their bachelor years, without knowing the terminology.

It then helps to illustrate these concepts with examples. For example that the determinant is a natural transformation, or that $\mathbb{C}[t]$ represents the functor forgetting the ring structure.

The more examples the merrier. I like Riehl’s example that in the category of graphs, the complete graph $K_n$ represents the functor assigning to a graph the set of all its $n$-colourings.

So, I had a look at the MathOverflow question Is Mac Lane still the best place to learn category theory?.

It is always a good idea to support authors offering a free online version of their book.

Abstract and Concrete Categories: The Joy of Cats by J. Adamek,H. Herrlich and G. Strecker. Blurb: “This up-to-date introductory treatment employs the language of category theory to explore the theory of structures. Its unique approach stresses concrete categories, and each categorical notion features several examples that clearly illustrate specific and general cases.”

Free online version : The Joy of Cats

Category Theory for the Sciences by David Spivak. Blurb: “Using databases as an entry to category theory, it begins with sets and functions, then introduces the reader to notions that are fundamental in mathematics: monoids, groups, orders, and graphs — categories in disguise. After explaining the “big three” concepts of category theory — categories, functors, and natural transformations — the book covers other topics, including limits, colimits, functor categories, sheaves, monads, and operads. The book explains category theory by examples and exercises rather than focusing on theorems and proofs. It includes more than 300 exercises, with solutions.”

Free online version: Category theory for scientists

Category Theory in Context by Emily Riehl. Blurb: “Suitable for advanced undergraduates and graduate students in mathematics, the text provides tools for understanding and attacking difficult problems in algebra, number theory, algebraic geometry, and algebraic topology. Drawing upon a broad range of mathematical examples from the categorical perspective, the author illustrates how the concepts and constructions of category theory arise from and illuminate more basic mathematical ideas. ”

Free online version: Category theory in context

Now, for the heavier stuff.

Simplicial Objects in Algebraic Topology by Peter May. Blurb: “Since it was first published in 1967, Simplicial Objects in Algebraic Topology has been the standard reference for the theory of simplicial sets and their relationship to the homotopy theory of topological spaces. ”

Free online version: Simplicial Objects in Algebraic Topology (h/t David Roberts via the comments)

A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology by Peter May. Blurb: “J. Peter May’s approach reflects the enormous internal developments within algebraic topology over the past several decades, most of which are largely unknown to mathematicians in other fields. But he also retains the classical presentations of various topics where appropriate. Most chapters end with problems that further explore and refine the concepts presented. ”

Free online version: A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology

Or in Lurie’s words: “To read Higher Topos Theory, you’ll need familiarity with ordinary category theory and with the homotopy theory of simplicial sets (Peter May’s book “Simplicial Objects in Algebraic Topology” is a good place to learn the latter). Other topics (such as classical topos theory) will be helpful for motivation.”

He also has a suggestion for the classic topos theory stuff:

“”Sheaves in Geometry and Logic” by Moerdijk and MacLane is a pretty good read (as is Uncle John, but I’ve never seen topos theory in there).”

I’ve had this book on permanent loan from our library over the past two years, so it’s about time to have my own copy.

Sheaves in Geometry and Logic: A First Introduction to Topos Theory by Mac Lane and Moerdijk. Blurb: “Sheaves arose in geometry as coefficients for cohomology and as descriptions of the functions appropriate to various kinds of manifolds. Sheaves also appear in logic as carriers for models of set theory. This text presents topos theory as it has developed from the study of sheaves. Beginning with several examples, it explains the underlying ideas of topology and sheaf theory as well as the general theory of elementary toposes and geometric morphisms and their relation to logic.”

Higher Topos Theory by Jacob Lurie. Blurb: “Higher category theory is generally regarded as technical and forbidding, but part of it is considerably more tractable: the theory of infinity-categories, higher categories in which all higher morphisms are assumed to be invertible. In Higher Topos Theory, Jacob Lurie presents the foundations of this theory, using the language of weak Kan complexes introduced by Boardman and Vogt, and shows how existing theorems in algebraic topology can be reformulated and generalized in the theory’s new language. The result is a powerful theory with applications in many areas of mathematics.”

Free online version: Higher topos theory

Although it is unlikely that I can use this left-over money from a grant to pre-order a book, let’s try

Theories, Sites, Toposes: Relating and studying mathematical theories through topos-theoretic ‘bridges’ by Olivia Caramello. Blurb: “According to Grothendieck, the notion of topos is “the bed or deep river where come to be married geometry and algebra, topology and arithmetic, mathematical logic and category theory, the world of the continuous and that of discontinuous or discrete structures”. It is what he had “conceived of most broad to perceive with finesse, by the same language rich of geometric resonances, an “essence” which is common to situations most distant from each other, coming from one region or another of the vast universe of mathematical things”. ”

And, as I also teach a course on the history of mathematics, let’s include:

Tool and Object: A History and Philosophy of Category Theory by Ralph Krömer. Blurb: “This book describes the history of category theory whereby illuminating its symbiotic relationship to algebraic topology, homological algebra, algebraic geometry and mathematical logic and elaboratively develops the connections with the epistemological significance.”

One Comment