At the moment I’m re-reading Siobhan Roberts’ biography of John Horton Conway, Genius at play – the curious mind of John Horton Conway.

In fact, I’m also re-reading Alexander Masters’ biography of Simon Norton, The genius in my basement – the biography of a happy man.

If you’re in for a suggestion, try to read these two books at about the same time. I believe it is beneficial to both stories.

Whatever. Sooner rather than later the topic of Conway’s game of life pops up.

Conway’s present pose is to yell whenever possible ‘I hate life!’. Problem seems to be that in book-indices in which his name is mentioned (and he makes a habit of checking them all) it is for his invention of the game of Life, and not for his greatest achievement (ihoo), the discovery of the surreal numbers.

If you have an hour to spare (btw. enjoyable), here are Siobhan Roberts and John Conway, giving a talk at Google: “On His LOVE/HATE Relationship with LIFE”

By synchronicity I encounter the game of life now wherever I look.

Today it materialised in following up on an old post by Richard Green on G+ on Gaussian primes.

As you know the Gaussian integers $\mathbb{Z}[i]$ have unique factorization and its irreducible elements are called Gaussian primes.

The units of $\mathbb{Z}[i]$ are $\{ \pm 1,\pm i \}$, so Gaussian primes appear in $4$- or $8$-tuples having the same distance from the origin, depending on whether a prime number $p$ remains prime in $\mathbb{Z}[i]$ or splits.

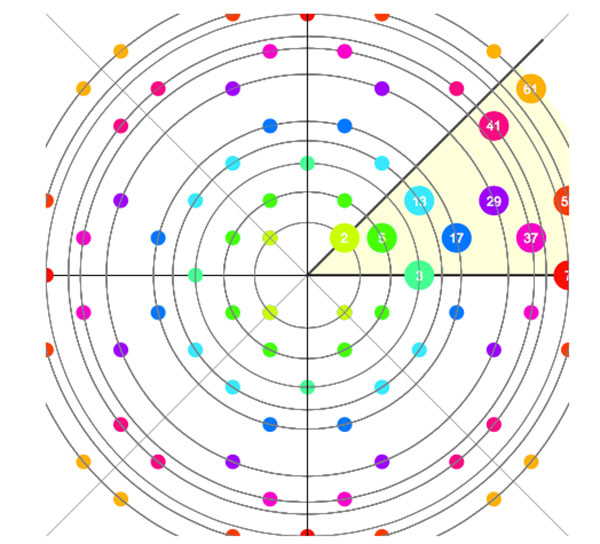

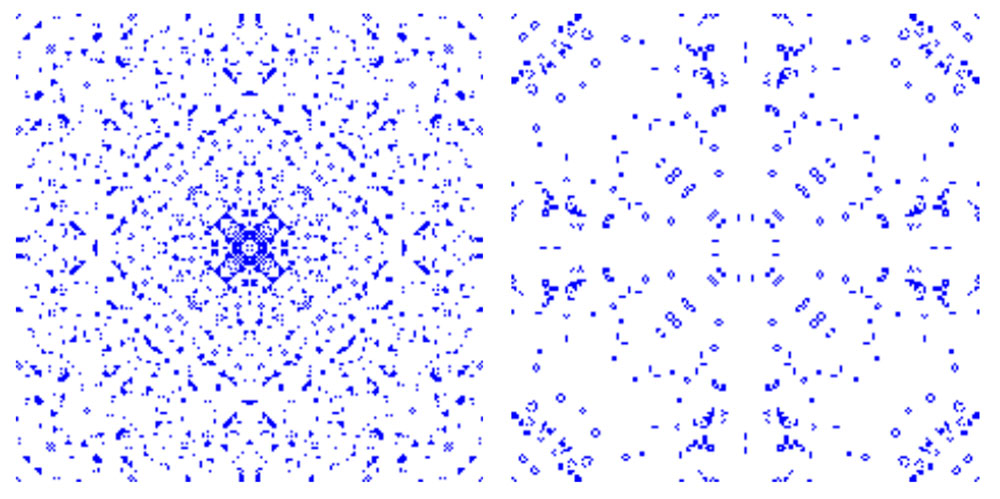

Here’s a nice picture of Gaussian primes, taken from Oliver Knill’s paper Some experiments in number theory

Note that the natural order of prime numbers is changed in the process (look at the orbits of $3$ and $5$ (or $13$ and $17$).

Because the lattice of Gaussian integers is rectangular we can look at the locations of all Gaussian primes as the living cell in the starting position on which to apply the rules of Life.

Here’s what happens after one move (left) and after three moves (right):

Knill has a page where you can watch life on Gaussian primes in action.

Even though the first generations drastically reduce the number of life spots, you will see that there remains enough action, at least close enough to the origin.

Knill has this conjecture:

When applying the game of life cellular automaton to the Gaussian primes, there is motion arbitrary far away from the origin.

What’s the point?

Well, this conjecture is equivalent to the twin prime conjecture for the Gaussian integers $\mathbb{Z}[i]$, which is formulated as

“there are infinitely pairs of Gaussian primes whose Euclidian distance is $\sqrt{2}$.”

2 Comments