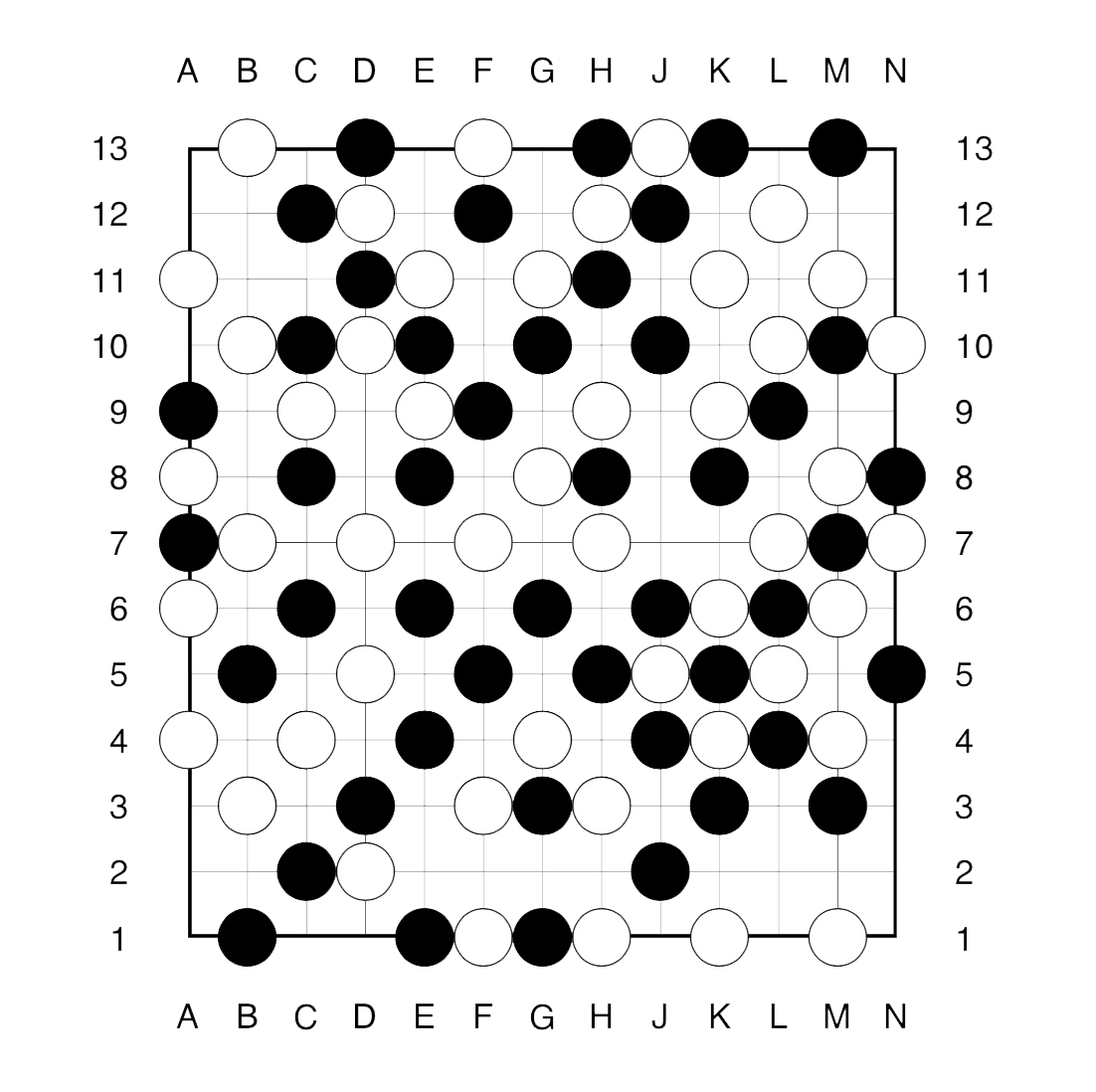

The largest snake in the moonshine picture determines the moonshine group $(24|12)$ and is associated to conjugacy class $24J$ of the monster.

It contains $70$ lattices, about one third of the total number of lattices in the moonshine picture.

The anaconda’s backbone is the $(288|1)$ thread below (edges in the $2$-tree are black, those in the $3$-tree red and coloured numbers are symmetric with respect to the $(24|12)$-spine and have the same local snake-structure.

\[

\xymatrix{9 \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{green}{18} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{yellow}{36} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{yellow}{72} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{green}{144} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & 288 \ar@[red]@{-}[d] \\

3 \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{blue}{6} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{red}{12} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{red}{24} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{blue}{48} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & 96 \ar@[red]@{-}[d] \\

1 \ar@{-}[r] & \color{green}{2} \ar@{-}[r] & \color{yellow}{4} \ar@{-}[r] & \color{yellow}{8} \ar@{-}[r] & \color{green}{16} \ar@{-}[r] & 32 } \]

These are the only number-lattices in the anaconda. The remaining lattices are number-like, that is of the form $M \frac{g}{h}$ with $M$ an integer and $1 \leq g < h$ with $(g,h)=1$.

There are

– $12$ with $h=2$ and $M$ a divisor of $72$.

– $12$ with $h=3$ and $M$ a divisor of $32$.

– $12$ with $h=4$ and $M$ a divisor of $18$.

– $8$ with $h=6$ and $M$ a divisor of $8$.

– $8$ with $h=12$ and $M=1,2$.

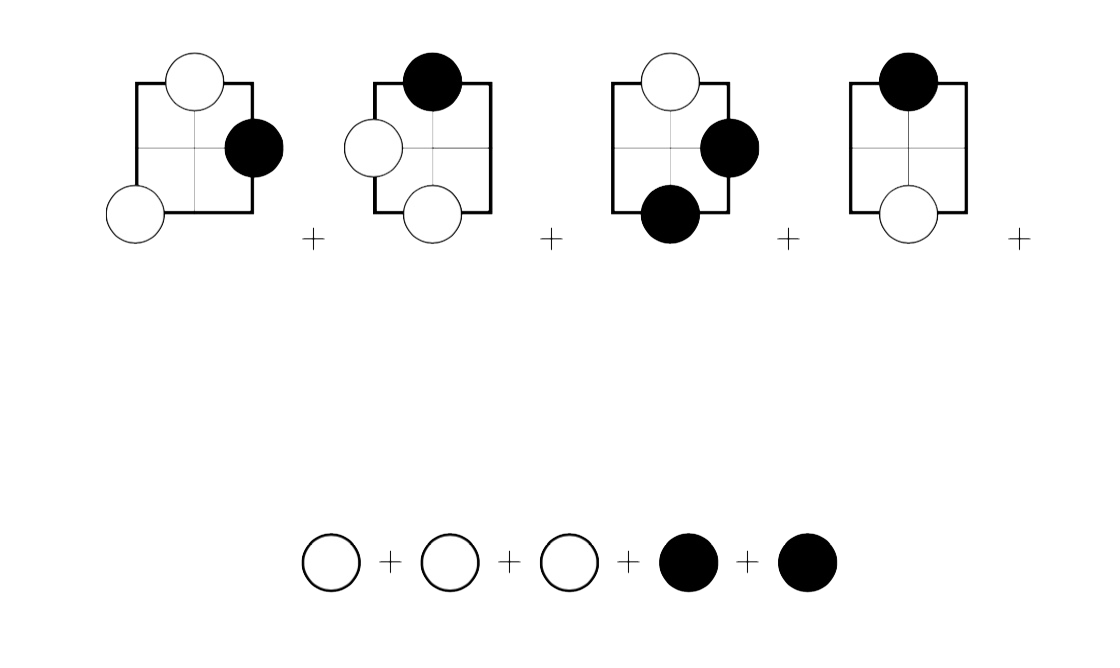

The non-number lattices in the snake are locally in the coloured numbers:

In $2,16,18,144=2M$

\[

\xymatrix{& \color{green}{2M} \ar@{-}[r] & M \frac{1}{2}} \]

In $4,8,36,72=4M$

\[

\xymatrix{M \frac{1}{2} \ar@{-}[d] & & M \frac{1}{4} \ar@{-}[d] \\

2M \ar@{-}[r] & \color{yellow}{4M} \ar@{-}[r] & 2M \frac{1}{2} \ar@{-}[d] \\

& & M \frac{3}{4}} \]

In $6,48=6M$

\[

\xymatrix{M \frac{1}{3} \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & 2M \frac{1}{3} & M \frac{1}{6} \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \\

3M \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & \color{blue}{6M} \ar@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[u] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & 3M \frac{1}{2} \ar@[red]@{-}[r] \ar@[red]@{-}[d] & M \frac{5}{6} \\

M \frac{2}{3} & 2M \frac{2}{3} & M \frac{1}{2} & } \]

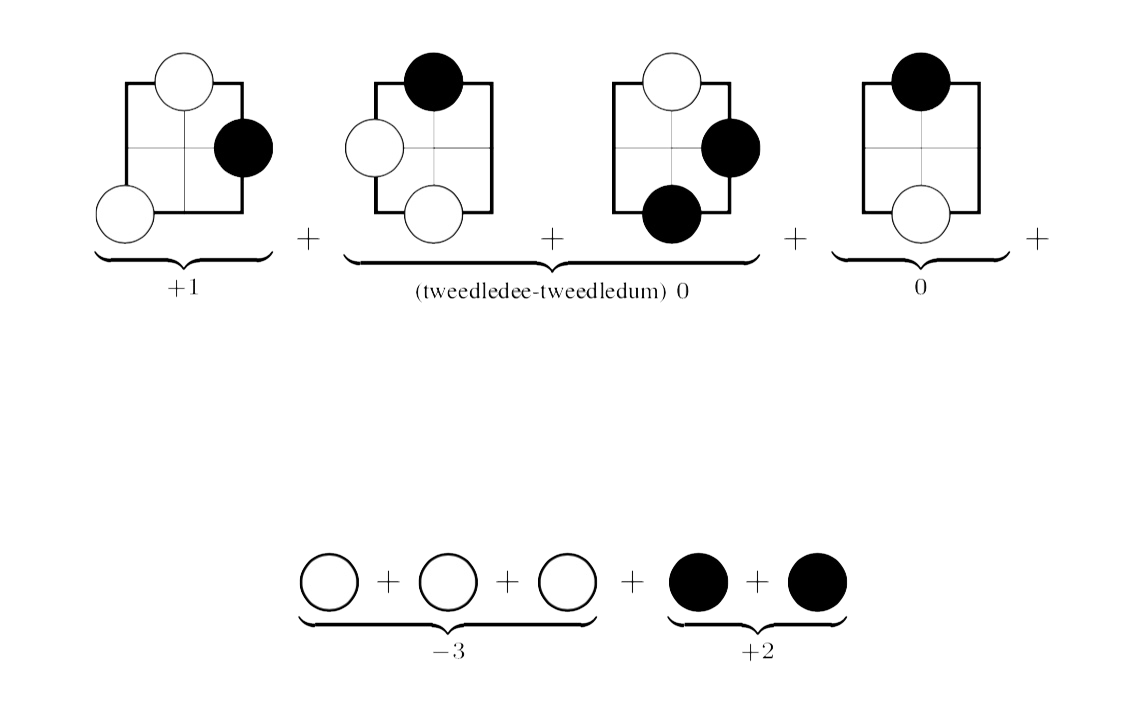

In $12,24=12M$ the local structure looks like

Here, we used the commutation relations to reach all lattices at distance $log(6)$ and $log(12)$ by first walking the $2$-adic tree and postpone the last step for the $3$-tree.

Perhaps this is also a good strategy to get a grip on the full moonshine picture:

First determine subsets of the moonshine thread with the same local structure, and then determine for each class this local structure.

Leave a Comment